While Narendra Modi was holding forth on Sunday morning about India’s strides in development on his watch, another Modi was counting his weekly wages 1,600km away in a corner of Bengal.

Labourer Modi, a man in his early 30s whose first name this newspaper is withholding for his protection, is paid Rs 800 a six-day week, which works out to less than Rs 134 per working day.

This is less than half the minimum daily wage of Rs 294 specified by the Bengal labour department. However, migrant labourers like Modi are given an advance during recruitment and are usually paid some additional money at the end of the seven-month working season.

“We are very poor. We work very hard but don’t earn enough for even two square meals a day,” Modi, who works for over 10 hours a day at a brick kiln in South 24-Parganas, said.

His wife too works at the kiln, at Rs 500 a week or about Rs 83 a working day. They have a toddler.

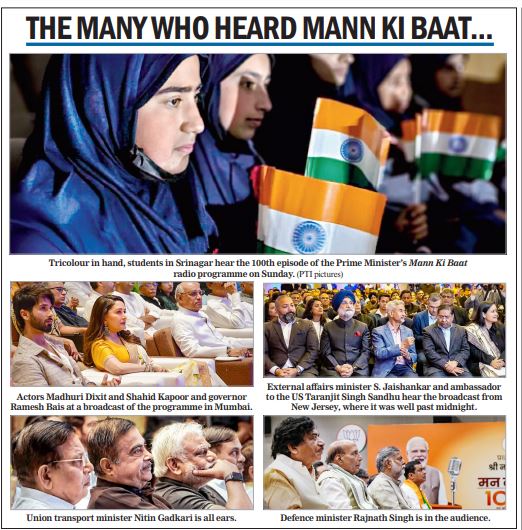

The "development" on which the Prime Minister spoke eloquently for over half an hour during the 100th episode of Mann Ki Baat, and which the saffron ecosystem celebrated through the day, appears to have eluded labourer Modi.

The Prime Minister claimed that his monthly radio broadcast had evolved into a “jan andolan (mass movement)”.

“Every episode (of Mann Ki Baat) was special in itself. Every time, the novelty of new examples, every time the extension of new successes of the countrymen…. In Mann Ki Baat, people from every corner of the country, people of all age groups joined," the Prime Minister said.

Had labourer Modi tuned in to listen to the Prime Minister’s message?

“No, we don’t have a radio.”

A television set?

“No.”

A smart phone?

“No.”

He elaborated: “I don’t know about the Prime Minister or any other minister. I have no time for politics or political leaders.”

Labourer Modi is an OBC with no landholdings in his native village in a neighbouring state. He never went to school and has no technical training. “I can only offer my physical labour,” the barrel-chested man said.

He has Saturdays off work, when he takes a steamer ride across the Ganga to Uluberia in Howrah to buy his weekly ration of groceries and other essentials.

“A part of my earnings goes into repaying debt.… We are left with very little money for us,” he said.

Modi had taken a loan of Rs 5,000 from the labour contractor, colloquially known as “Sardar”. Many other workers at the brick kiln too are toiling to repay their debts.

“Seasonal migrant families from Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh and Chhattisgarh come to Bengal with the help of illegal and unregistered contractors and middlemen, who pay them an advance at source to bring them in,” said Alamgir Mollick, a rights activist who works with migrant labourers and their children.

The “advance” is actually a loan that ties the recipients to debt, forcing them to virtually work as bonded labour, which is the system of forcing someone into servitude through debt. The “advance” usually ranges from Rs 30,000 to Rs 75,000, but can be much lower, as with Modi.

“The labourers settle the payment at the end of the season, when they return home. They work under restrictive conditions that carry shades of bonded labour and violate the Bonded Labour (System) Abolition Act (BLSA), Inter-State Migrant Workers Act and the Minimum Wages Act,” Mollick said.

Bonded labour is prohibited under Articles 21 and 23 of the Constitution and the BLSA of 1976.

However, the practice serves as the primary source of income for a large segment of the country’s population, especially among the marginalised communities of Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh.

Bengal is estimated to have over 11,000 brick kilns, most of them employing migrant labourers from neighbouring states. The kilns employ 35 to 80 families each every season.

For every 1,000 bricks a family helps make, it is paid between Rs 250 and Rs 600, depending on the quality. A part of the money is paid as a weekly wage. The “advance” is deducted from the final payment, made at the end of the season.

“Some kiln owners don’t pay the entire amount, forcing the labourers to return the next season,” Mollick said.

South 24-Parganas district magistrate Sumit Gupta said: “We visit the brick kilns regularly to check if they are being run properly and legally. We have not been told of any labourer being made to work forcibly in these kilns. If we get any specific or written complaint, we will act on it.”

According to the Global Slavery Index 2021, an estimated 8 million people in India live in conditions of modern slavery, including bonded labour.

It is difficult to get an accurate estimate of the number of people in bonded labour. The practice often goes unreported, and many of the victims are isolated and exploited in remote areas where they have little access to legal or social services.

“The migrant workers who lost their jobs because of the pandemic were rarely taken back into their old jobs after the lockdown was lifted,” economist and activist Prasenjit Bose said.

“Most of these jobs had vanished as there had been negligible economic development…. Now, amid the lack of opportunities, it will not be very surprising if an upward surge in bonded labour is noticed. Although the actual data is yet to come out, this is the most likely situation.”

Data available from the official website of the Union ministry of labour and employment suggests that BJP-ruled Uttar Pradesh has the highest number of people working elsewhere as migrant workers.

Of the country’s total migrant labourer population of 288,827,476 (about 28.9 crore), about 8.3 crore come from the heartland state.

Bihar and Bengal hold the next two positions, with figures of nearly 2.85 crore and 2.6 crore, respectively.

“Who wants to leave his home state and go elsewhere to work and live like this?” labourer Modi asked, pointing at the array of mud-and-brick rooms that are provided to workers like him to stay in.

Have the benefits offered by the Centre — such as housing under the PMAY scheme — reached him?

“Sir, we are poor, lower caste people. Who thinks of us?” Modi said, sharing his mann ki baat.