A black-and-white shot of a cabaret performance at Folies Bergère, Paris, dated 1959, catches the eye with its play of light and shadow.

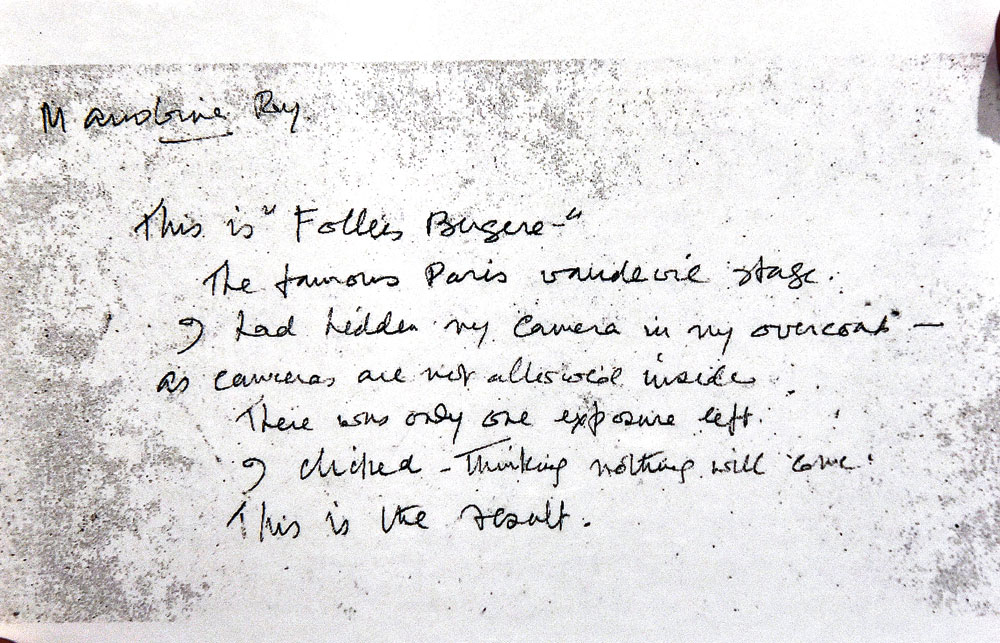

The picture comes with a confession: “…I had hidden my camera in my overcoat — as cameras are not allowed inside. There was only one exposure left. I clicked —thinking nothing will come. This is the result.”

The photographer was Manobina Roy, one of India’s earliest women photographers and wife of filmmaker Bimal Roy. The frame is one of the 80 on display at The Harrington Street Arts Centre. A Woman and Her Camera, Manobina’s first solo exhibition, has been curated by her son Joy Bimal Roy, almost 18 years after her death, to mark her centenary.

Photograph of Folies Bergère in Paris

“I knew my mother loved photography and had a natural flair for it. But I had no idea she was one of the pioneers in India or about the extent of her achievements till I read Chhobi Tola: Bangalir Photography-chorcha by Siddhartha Ghosh after her death in 2001. Ma never spoke of her achievements to her family,” Joy said.

Manobina’s adventures with the camera began when she was 12. She, and her twin Debalina, received their first cameras — Eastman Kodak-made Brownie — as birthday gifts by their father, principal of a school in Ramnagar, Uttar Pradesh.

In 1931, when most girls their age would either be married off or be prepared for matrimony, the twins were busy discovering the joys of photography.

Manobina Roy’s note with her photograph of Folies Bergère in Paris. It reads: This is “Folies Bergère”— The famous Paris vaudeville stage. I had hidden my camera in my overcoat — as cameras are not allowed inside. There was only one exposure left. I clicked — thinking nothing will come. This is the result

Their father Binod Behari Sen Roy had also built a dark room for the girls to develop their pictures. So from two mischievous girls who loved giving their tutor a hard time, they evolved into ace photographers exhibiting in group shows.

Soon, Manobina became a member of the United Provinces Postal Portfolio Circle, a group created by the Photographic Society of India. But marriage at 17 put a stop to what could have been a promising career.

“My mother happily gave up her talent for marriage. She just expressed regret to me once, during a photography exhibition of my father’s. She hardly ever spoke of her journey as a photographer,” Joy said. “My mother would preserve most of her pictures in a trunk.”

Manobina, however, continued to capture on camera her life, travels and family in between responsibilities.

The photographs on display at The Harrington Street Arts Centre reveal Manobina’s love for the play of light and shade. “She used only natural lighting. I think she was ahead of her times. In an era of studio photography and flat lighting, she was brave enough to play with shadows. So, her monochromes are timeless,” Joy said.

Pictures of her children, grandchildren, pets and people she met during her travels dominate the collection. A lover of aesthetics, some of her monochromes capture 20th century fashion in Europe, too. Some early photographs depict landscapes of Ramnagar in the 1930s.

Many of the pictures come with handwritten anecdotes. A shot of two elderly European women emerges as a poignant tale: “Two old ladies meet on the road in London just to say ‘what a lovely day’. They are so lonely that just to talk to someone is a relief.”

Manobina, according to her son, remained “an avid photographer till almost her last days when she was too ill to click anymore”.