In November 2008, Lalgarh in the then West Midnapore district, witnessed a change. Hundreds of thousands of villagers joined a movement to express their angst with the Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee government and this dusty corner of Bengal — around 40km from Jharkhand border — became the hotbed of Maoist extremism.

In around three years and six months, 264 lives were lost — 217 CPM activists, 22 rebels and 25 men in uniform.

Ten years since the uprising, which led to a crackdown by security forces, and its natural death in 2011, Lalgarh, which is now a part of Jhargram district, is no longer the same place. Since the change of guard in Bengal, Mamata Banerjee visited the area a number of times and the state government launched several development initiatives.

Pranab Mondal of The Telegraph visited the area in the second week of November this year to see today’s Lalgarh.

Four youths, including a teenage girl, are queuing up in front of a tin-roof shop with a picture of Anushka Sharma on the rear concrete wall at Kantapahari Bazar in Lalgarh.

With smart phones, priced between Rs 4,000 and Rs 8,000, the youths have turned up at the biggest outlet in the small market to utilise their communication devices as entertainment tools.

“I am here to download some songs,” said Ananta Mahato.

Once done, Ananta plugged in his earphones, rode his motorcycle shaking his head with the rhythm of a song and left the market, around 30km from Jhargram town.

The youth in his mid 20s represents today’s Lalgarh, which is markedly different from what the place was a decade ago.

Lalgarh was like any other deprived and under-developed village in Jungle Mahal — comprising Belpahari, Banspahari, Bhulaveda, Simulpal and Odolchua.

Lalgarh was regarded as one of the most under-developed regions in the state — till a convoy carrying former chief minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee was targeted by Maoists on November 2, 2008.

Following the blast, the security agencies launched massive crackdown in Lalgarh suspecting the masterminds behind the attack were camping there.

The villagers didn’t like the “excess” and a movement — with the support of Maoists, who were trying to mobilise youths to join their armed struggle — started.

Initially, a siege was imposed on the 13km stretch between Lalgarh and Ramgarh by the Maoist-backed People’s Committee against Police Atrocities (PCAPA), which shortly spread to around 170sqkm area.

Maoists stepped out of their hideouts in dense forests and started roaming openly with automatic rifles and meetings villagers to guide them about their next course of action.

Most youths in the area joined the movement after the rebels took them into confidence saying they were deprived of their rights by the then Left Front government.

The rebels cashed in on the villagers’ ire with underdevelopment and CPM leaders in the area became the target of the local youths.

A large section of them picked up arms against police and CPM men while others were engaged to collect intelligence about the movements of security agencies.

Raids by the police became a regular feature and surveillance intensified prompting the youths to leave their homes and take shelter in the dense forests in Punnapani, Rameshwarpur, Lakshmanpur and Hatilot.

Youths like Swapan Hembram and Asish Mahato, whom this correspondent met, seemed a different lot. Although all of them said they knew about the strife 10 years ago, most of them expressed their lack of interest in the past and wanted to talk about the need for development.

“The movement was against police atrocities and corrupt CPM men. We met both the targets. Now, we need roads, jobs, schools, public amenities and rationing system. Violence doesn’t work nowadays,” said Asish, a protestor of 2009, who is now a worker under a contractor engaged in government projects.

Police sources said the area had actually witnessed a remarkable slump in crimes since the change of guards in the state in 2011.

“The trouble makers, mostly PCAPA activists, and CPM men switched loyalty to Trinamul. It is the main reason for the change in the crime-graph,” said an officer of Lalgarh police station.

Local Trinamul leaders attributed this change in Lalgarh to Mamata Banerjee.

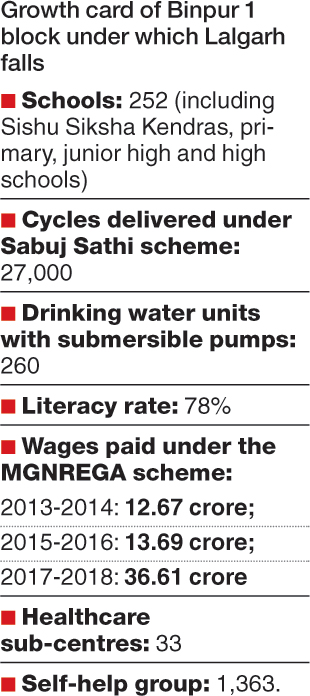

Lalgarh is dotted with signs of development as new roads, new educational institutions and training centres for youths can be seen. In the villages, one can see beneficiaries of government schemes (see chart).

The changes may have modified Lalgarh’s look, but people living in the areas feel some of their old problems still persist.

“Some people have been made civic volunteers, but only those connected with the ruling party have got those jobs. We cannot do farming as the irrigation problems persist. We have been promised proper healthcare, but nothing has been done,” said a resident of Chotopelia, preferring anonymity.

Several residents this correspondent spoke to said while some changes did come into their lives, they were still deprived of many things.

“Some people with the ruling party have gained immensely. These people are making money from the government projects and schemes. Earlier, CPM leaders had all the money, and now they have been replaced by Trinamul leaders and their associates,” said a resident of Chotopelia, preferring anonymity.

He added that the tradition of toeing the diktats of the powerful continue in Lalgarh.

“We could not raise voice because of atrocities by local CPM leaders. During Lalgarh movement, we had to echo Maoists voice and could not protest their merciless killings. Now, we cannot raise voice against the Trinamul leaders’ corruption. Our plight hasn’t changed much,” said the man in his late 30s.