Lack of enough doctors, reluctance among a section of doctors to take responsibility and the state government’s inability to create a strong emergency care system are some of the major problems that have come to light in the first few days of the new referral system for government hospitals.

Added to the problem is a new technology that many health officials and government hospital administrators think needs modifications if the referral system has to function properly.

“We are reviewing the system and trying to spot the loopholes,” a health department official said.

On Saturday, a meeting was held at Swasthya Bhavan to review the functioning of the referral system. The system, one of the demands of the protesting junior doctors, was rolled out on November 1, following the launch of a pilot project.

Hospitals in districts are supposed to refer patients, if they are unable to treat them, to five government medical colleges and MR Bangur Hospital in Calcutta through the new system. The five medical colleges are SSKM-IPGMER, Medical College Kolkata, NRS Medical College, RG Kar Medical College and National Medical College.

Metro reported on November 5 that the referral system had yet to take off. Patients were still being referred from district hospitals with handwritten instructions instead of through the online portal, as the new system demands, and denied treatment in the city.

“We will review each referral from peripheral hospitals to verify whether the patient needed to be referred to a better facility,” the health department official said.

This newspaper interviewed hospital administrators, health department officials and public health experts to identify the problems faced by the new referral system.

Lack of enough doctors and reluctance to treat: “The referral system cannot succeed unless the government recruits more doctors. At many hospitals, there are too few senior specialists. They struggle to treat patients already admitted and those at the OPDs. They are overburdened,” said an official at a government medical college.

According to sources, there are a couple of senior doctors in the medicine ward and another for tropical medicine at MR Bangur Hospital. The ward has 250 beds.

“Coupled with the problem resulting from the shortage of staff is the tendency of a section of doctors to not take responsibility and refer patients to another hospital on the slightest pretext,” said the chief medical officer of health in a district.

“Even if we recruit more doctors, the problem will not be solved if the wave of unnecessary referrals from peripheral hospitals can’t be stopped,” said an official in the health department.

“That is why we are reviewing the referrals. The burden on the medical colleges needs to be reduced.”

A doctor at a rural hospital said the history of harassment and assault by patients’ relatives after a bad treatment outcome often forces them to refer patients, especially those whose condition may turn critical, to a facility that is supposed to have more specialist doctors and a better set-up.

“The state administration has to provide more protection for doctors at the primary and block level hospitals,” he said.

Emergency care: The Emergency departments at most government medical colleges have beds for “observation” where critical patients are stabilised before being shifted to indoor wards or referred elsewhere.

“There is a need to create proper Emergency wards where patients can be treated for a day or two. The Emergency wards should also have facilities for surgery and other procedures,” said the medical superintendent of a medical college.

“If that is done, a patient referred from a peripheral hospital can be treated in the Emergency till an indoor bed can be arranged. This will help address complaints of patients being turned away from medical colleges without treatment for lack of beds,” he said.

The Emergency rooms at many private hospitals in the city are equipped with such facilities.

“We have beds with ventilators in the Emergency room where patients can be kept for several days if indoor beds are unavailable. This was particularly helpful during the Covid pandemic,” said the CEO of a private hospital.

A health department official said the Emergency rooms are mostly run by “general duty medical officers”, who are not specialists.

“There is a provision for specialists to visit the Emergency room but that seldom happens. We are trying to find ways to make the emergency medical care system more robust,” said the official.

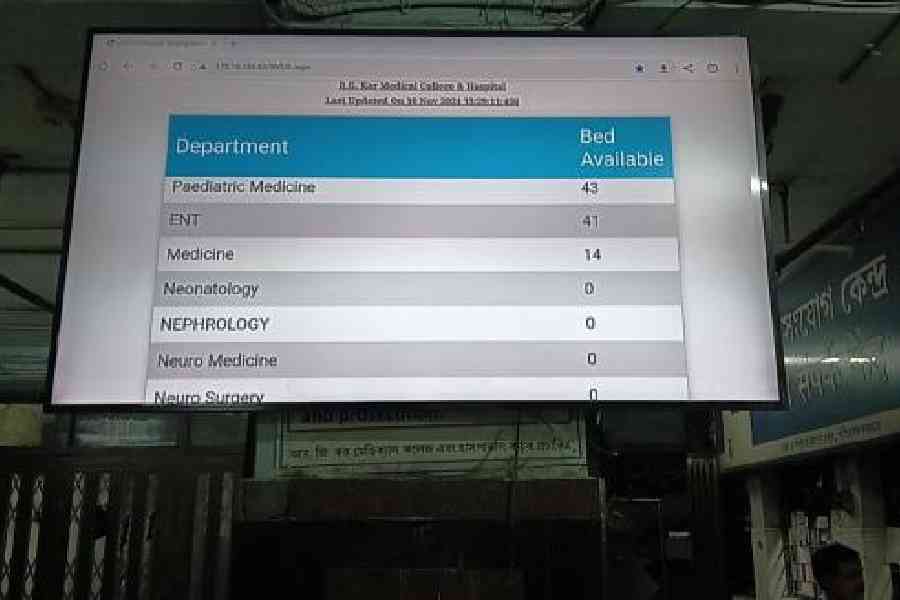

Technology: In the new system, a hospital referring a patient sends the request for a bed to the destination hospital online. The hospital has 30 minutes to respond. If it fails to do so, the new system automatically accepts the request.

“On paper, the patient is informed that a bed is available at the referral hospital. But often when the patient reaches the hospital, he or she is told that no bed is available,” said a hospital administrator.

Also, the system faces glitches at several medical colleges.

“There should be a central referral panel to supervise the whole process. Otherwise, such problems will keep recurring,” said a health department official.

Bed distribution: A senior health department official said many specialist doctors at government medical colleges hold on to their allotted beds even if there are fewer patients.

This creates an artificial bed crisis and patients needing admission in other disciplines are denied treatment, he said.

“We are planning a system where senior specialists cannot hold on to more than 80 per cent of the allotted beds if those are not occupied. The vacant beds will be part of the general pool,” the official said.