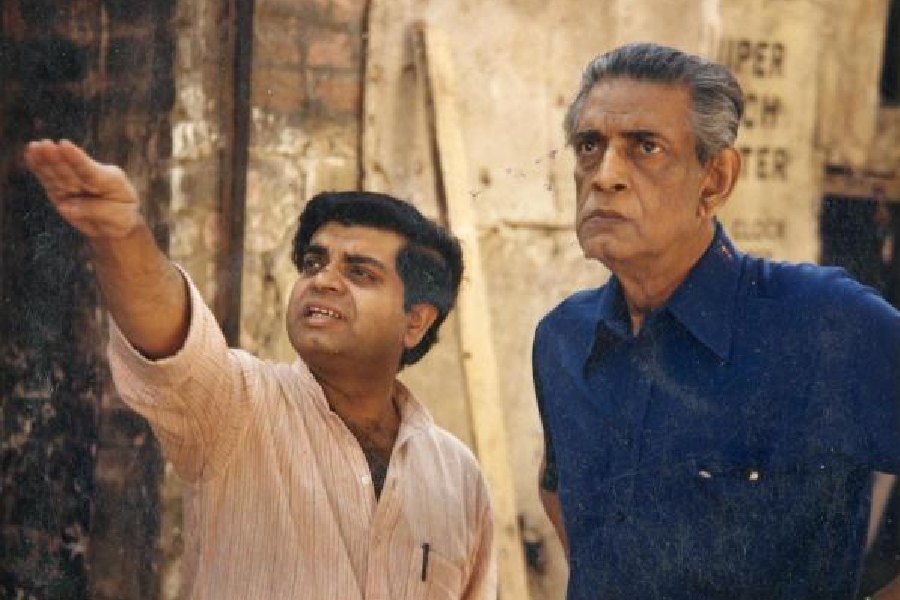

Even if you shoot a scene with extreme hard work and dedication, it must be discarded if it doesn’t look good on the editing table. The ruthlessness and discipline of Satyajit Ray while cutting his own film was one of the lessons that his son, filmmaker Sandip Ray, shared with students of Techno India University recently.

“Baba always paid attention to the film’s pacing, making editing a daunting task for us. For him, a film must be lean and fatless, “ Sandip said. The director of films like Royal Bengal Rahasya and Hatyapuri was the guest for the fourth episode of Unwind-Boi Kotha Kow, a talk show series hosted by the Techno India Group.

Titled “The magic of storytelling with cinematic masterpieces,” the conversation with Manashi Roychowdhury, co-chairperson of the Techno India Group, had Sandip discuss his journey in cinema, the influence of his father and how he has continued the cinematic legacy.

“From my formative years, I was exposed to shootings and cameras, though I lacked any real understanding. I remember the shooting of Pather Panchali when I was a child. Our home was frequented by foreigners. My father received letters from different countries and I collected the stamps. I didn’t realise that the familiar faces around us were renowned actors.”

Despite his professional commitments, Satyajit Ray was always a family man, ensuring that his wife and son stayed with him by scheduling outdoor shoots during Sandip’s school holidays. “I have vivid memories of the shoots. I was fascinated when Baba shot a scene using a crane. The steam engine shoots were also captivating,” he recalled.

Sandip also discussed the pressures and advantages of being the only son of a legendary filmmaker. While shooting his first movie Phatik Chand, he said his father visited the set but was not allowed to watch the shooting. When the film was released, it was rumoured that Satyajit had directed it. But this also gave Sandip a sense of satisfaction in meeting expectations.

After his father’s heart attack, when he missed the studio atmosphere, Sandip brought him back to the sets, which his father greatly enjoyed. “Another thing I appreciated about Baba was that he never interfered in my films. He watched Phatik Chand and told me that it was too long. However, he didn’t guide me on where to make the cuts,” he said.

Roychowdhury asked him to compare the films from the early years of senior Ray’s career to the later years. “We don’t usually shoot films in sequence, but Pather Panchali was shot that way as he was still learning. He later felt that the ending was better than the beginning,” Sandip replied, adding that his father regarded Charulata as his best creation. “He thought it was flawless.”

When it came to casting, Sandip felt that his father had an “incredible inner eye”. “He rarely held tests or workshops. There were instances when he cast people just by interacting briefly. He didn’t guide the actors much and let them decide how to act. His imposing 6.4ft height often intimidated actors,” Sandip laughed.

Another remarkable feature was how Ray Senior dealt with child actors. “He always sat and interacted with them as if he were their age,” Sandip added.

The conversation turned to the children’s magazine Sandesh, founded by his great-grandfather Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury and subsequently run by his grandfather and father. As the current editor, Sandip was asked by Roychowdhury about the challenges of continuing its publication. He explained that the magazine was now primarily targeted towards the Puja edition. “Today’s kids are not as accustomed to reading as we were and many prefer reading English translations of Bengali texts. The quality of writing has also dropped. Sometimes we reprint stories to maintain the magazine’s legacy,” he replied.

Sandip also spoke of the extensive research his father conducted on the settings of his movies. “Satyajit Ray had never visited the places where Professor Shonku travelled, while he had done so for the locations featured in Feluda stories. For Professor Shonku, he wrote letters to friends in those regions, seeking detailed information, including street maps, to accurately depict the settings,” he said.

Sandip said he enjoyed working on his father’s short stories, such as Jekhane Bhooter Bhoy, and wants to adapt another short story for his next project. “My father’s working room is yet to be fully explored. There might be undiscovered treasures like short stories and illustrations waiting to be discovered,” he said.

The floor was then opened to the audience. Ishika Mitra, a second-year media science student, could not contain her excitement as she asked Sandip what the most important element in detective films was. The filmmaker explained that Satyajit Ray’s two Feluda films were crafted as thrillers because he believed that the traditional whodunit format would not be widely accepted. In contrast, Chiriyakhana, the Byomkesh Bakshistory, was shot as a whodunit.

Sandip said he used the whodunit format himself for television adaptations but returned to the thriller format while shooting Bombaiyer Bombete. However, he acknowledged that the new generation prefers the classic whodunit format.

Oishi Sen, an MBA student, wanted to understand the difference in storytelling between old films and current ones. One of the biggest challenges in today’s world, Sandip explained, was the significantly decreased attention span of audiences. Ultimately, he noted, audiences still appreciate good storytelling.

Sujoy Biswas, director and CEO of the Techno India Group, spoke of his wife getting replies to her letters from Satyajit and wondered how he found the time to write back to children. Sandip answered that Ray had exceptional time management skills. “He divided his days meticulously, dedicating his mornings to writing or replying to children’s letters. He drafted many letters and spent considerable time on this task. He was truly a genius in managing his time,” his son said.

In conclusion, Ray emphasised what his father believed in: to be a good, honest and dedicated person is essential to become a good storyteller.