Memory can transform much. A beloved neighbourhood can turn into the skeleton of a giant fish, touched back to life.

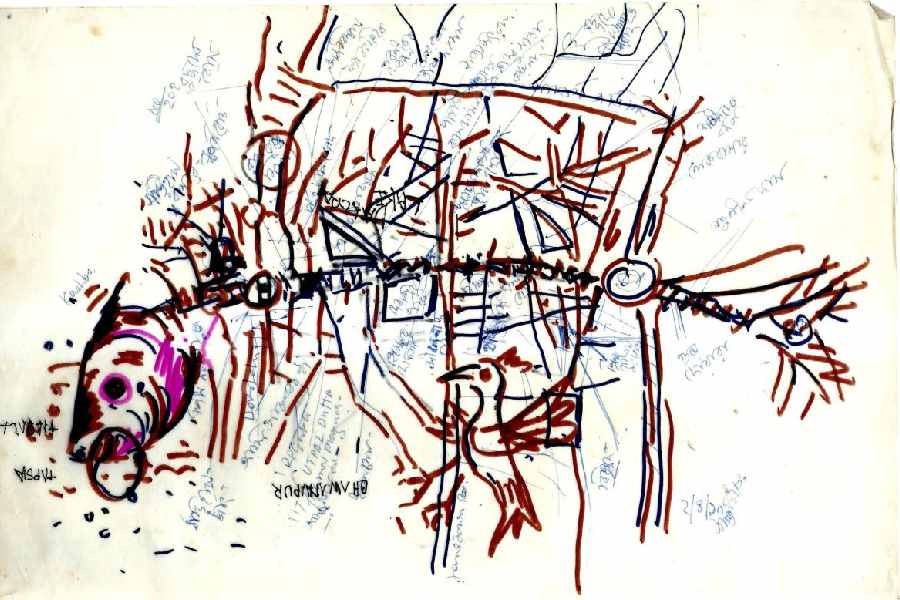

Among artist Shanu Lahiri’s notes was found an account of Rashbehari Avenue starting from the Fifties. Accompanying the words of the artist, painter, sculptor and maker of large public murals was a sketch that imagines the avenue as the vertebral column of a fish, with its head fallen near Kasba, tail lying near the Rashbehari Gurudwara. It must have been dropped by a bird. One is seen hovering on the edges. Where the rest of the body of the fish was, is the map of the two sides of the avenue, crowded not so much with localities as the names of the most famous residents of this south Calcutta area.

Lahiri’s account is evidence that celebrity was not isolated from common life so much then. This is a map of Lahiri’s early years and also of the vibrant cultural life of Calcutta, concentrated on the two sides of Rashbehari Avenue then in such a high degree that it looks unfair. This is a city — and a culture, and not only of the arts but of living itself — that is lost forever. Lahiri’s account, written in Bengali, starts with the tramline along Rashbehari Avenue.

“The tram is moving from Gariahat Market towards Lake Market, through freshly grown green grass, with its dinging bell” — but the buses are charging at each other in their rush. At night the place changed. “We would keep walking for long on the footpaths without a care, chatting,” writes Lahiri. “Chai, bel phool chai,” the flower sellers would cry. “I felt an intoxication,” says Lahiri. Memory can take on a dreamlike quality. The Rashbehari Avenue of Lahiri’s memory certainly looks a bit of a dream compared with what it is now. Currently, it is turned into a tunnel with huge Puja billboards lining the sides. The red of the post-boxes and fire brigade boxes showed brilliantly against the green of the grass. And a living legend could descend from a rickshaw any moment.

“I was waiting at Gariahat with my son for a tram when I saw the famous magician P.C. Sorcar getting down from a rickshaw to buy a bamboo flute.” Lahiri would often spot musician and composer V. Balsara walking about in the area. She prepared this note when she was asked to speak at the 100th birth anniversary of writer Buddhadeva Bose. “I don’t know much about literature,” writes Lahiri.

Her murals in public places had changed the city’s appearance, even if a little. Her sculpture Parama at the Science City island was a city landmark till it was replaced by the Biswa Bangla icon. The city was very dear to Bose. Lahiri also knew that Bose, who contributed to introducing modernity to Bengali literature in a major way, did not like the renaming of streets and localities.

Lahiri’s family lived in the same street as Bose, in Rashbehari Avenue opposite Triangular Park. On the floor above Bose lived poet Ajit Datta, whose daughter Sharbari Datta became a leading fashion designer. Lahiri’s family, including her eminent brothers, writer Kamal Kumar Majumder and painter Nirode Mazumder, lived on the ground floor.

On the floor above lived actor and stage personality Utpal Dutt with his family. Singer Utpala Sen would visit the second floor at times. Nirode Mazumder was part of Calcutta Group, a group of modern artists, founded in Calcutta in the Forties. The Majumder household would often be visited by members of this radical group. So, at the lecture, Lahiri spoke about the place where Bose lived. It was nothing short of a cultural register.

The names of other residents of the Rashbehari Avenue area tumbled out: linguist and educationist Suniti Chattopadhyay; former Union education minister Triguna Sen; writers Naren and Radharani Deb, whose daughter was writer Nabanita Dev Sen; former chief minister Jyoti Basu; entrepreneurs Shibu and Arati Chakraborty; Academy of Fine Arts member K.D. Ghosh, to name only a few.

The Jignasa bookstore would be visited by critic Shibnarayan Roy, Pulin Sen and singer Debabrata Biswas. Sarod player Ali Akbar Khan lived in a house next to Hindustan Mart with his family, and a world would form around him, full of music, conversation and laughter.

“He would walk in the evenings along Rashbehari Avenue, chatting with others, and stop at Hemenbabu’s instrument shop to sit down on a broken chair and talk about music. Many musicians would come here: Shishirkana Dharchowdhury, Manilal Nag, Nikhil Banerjee, Buddhadeb Dasgupta, Bahadur Khan, V.G. Jog….” The Sadarang and Dover Lane music conferences would be like carnivals and turn Ali Akbar Khan’s house into a musicians’ community. Near Lake Market the lean figure of poet Bishnu Dey, clad in impeccable white dhuti and punjabi, could be seen approaching, on the way to the tram.

His house was a hub, too — artist Jamini Roy, scientist Satyen Bose, communist leader P.C. Joshi, theatre personalities Sombhu and Tripti Mitra and singer Suchitra Mitra were regulars. Lighting designer Tapas Sen, mime artist Jogesh Datta and his brother Manu Datta lived in the Rashbehari area. Writer Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay had lived here.

So did collector, writer and raconteur R.P. Gupta and sculptor Debi Prasad Roychowdhury. Lahiri’s list is very long. Actors Pahari Sanyal and Sadhana lived here. “Composer S.D. Barman used to live next to Lake Market,” writes Lahiri. She remembers Kamal Chowdhury’s mishti shop Madhukkhara, particularly its nikhutis, another fried delicacy in syrup that has vanished.

Suvo Guha Thakurta’s Dakshinee school, which taught Rabindrasangeet, was famous. Partha and Kalyani Ghosh founded Thema, their publishing house, which was located in the area.

Wafts of music would float out of the music store Melody. Near the gurudwara, Achin Patua would be spotted. Lahiri and her friends from art school would visit the gurudwara for its calm, and enjoy the halwa.

Jibanananda Das, one of the greatest Bengali poets, lived near Deshapriya Park. He lost his life after being hit by a tramcar on Rashbehari Avenue. Lahiri remembers a spectacular residence near Aleya cinema with a long gravel path, glass covering the gravel and a fish pond. She finally mentions her friend Dashu-da, a Triangular Park neighbour, who decided one day that he would live in a caravan. Magazines were bought from abroad. Many months were spent creating a design. A lot of his money and emotions were invested and a fine and elaborate caravan was built.

It was fit to be driven anywhere in the world. But not alas, on the streets of Calcutta. Because the vehicle was so much wider than the roads. The caravan was deserted. Trees grew from it and it gradually became a skeletal structure. But after darkness, the moon could be glimpsed through it.