In Rabindranath Tagore’s short story Jibito O Mrito (The living and the dead), a woman presumed dead comes back, but no one, including herself at times, believes that she is alive. In the end, she jumps into a pond and kills herself to prove that she had been alive.

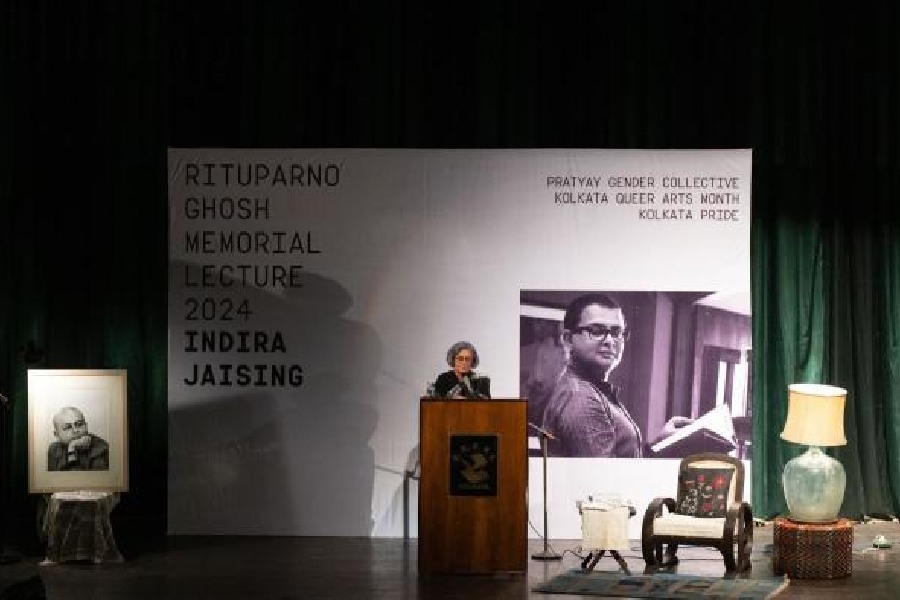

The law, too, takes a dead woman more seriously than a living woman. “The dead body speaks for itself. The living woman also speaks for herself, but her word is not accepted,” said Indira Jaising, eminent jurist, lawyer and activist, who delivered the 2024 Rituparno Ghosh Memorial Lecture here on December 21.

Titled “Sexual assault, outrage and the theatre thereafter: Triggers of a public-judicial response or its lack”, the talk addressed in particular how rape and death were inextricably linked.

Enumerating cases of sexual violence in the last five decades, from the Mathura case to the RG Kar rape and murder, Jaising said she found a few features of the law disturbing.

She has appeared in landmark cases for women’s rights and human rights, including the Rupan Deol Bajaj case, the Sabarimala temple case and the Kathua rape case. She has represented the Bhopal gas tragedy victims and activist Teesta Setalvad. Recently, she appeared in the Supreme Court for junior doctors in the RG Kar case.

“Throughout my career, I have seen that nobody takes any notice of a woman who is complaining that her bodily autonomy is being violated. Rape of a wife by her husband is not an offence,” Jaising told The Telegraph.

“It means I have no autonomy, I don’t own my own body. This has been a very disturbing feature of the law,” she added. “Yet when the woman dies, the judges will say this should not have happened. But what were they doing when she was alive?”

If we are to talk about justice, she said, we have to understand that the only property we own is our bodies. “That is why the living body is so important to me.”

Death is incontrovertible proof that violence was done to the woman.

“The dead body can tell no lies. A good forensic scientist can tell how the murder was committed. That is why the dead body is often eliminated so fast,” said Jaising.

The body of the young Dalit woman who was gang-raped in Hathras was cremated in a hurry and not handed over to her family.

“It is important for me to talk about life, death and rape in the same breath so that we understand that it is a very specific kind of violence against women,” said Jaising.

“Law is about language,” she said. “Look at the way (Dalit scholar) Rohith Vemula was killed. We called it an institutional murder. Since then we stopped saying someone had committed suicide. We say ‘death by suicide’. So I wanted to transpose that idea to the question of rape and that’s why I would use the phrase ‘death by rape’. Because the two go together,” she said. “A rapist finds it necessary to kill the woman.”

Jaising has appeared in the Mary Roy case that led to equal inheritance rights for Syrian Christian women; the Rupan Deol Bajaj case on sexual harassment, for Githa Hariharan, which led to the recognition of the mother as a natural guardian of a child; and the Sabarimala case where the temple management did not allow women of menstruating age to enter the shrine.

But sometimes even death is not enough for women. “So that will bring up the question of what is justice. Is it giving a life sentence to the accused? Is it giving death penalty as has been done by Bengal recently? A death penalty only encourages the rapist to kill,” Jaising said.

“The question is how is the context going to change?” she asked.

Here one can consider the impact of the women’s movement in India. “We can’t overlook the successes of the movement which took a step back from the incident itself and then focused on the context,” Jaising said.

In the case of Roop Kanwar, who “became” a sati in 1987 in Rajasthan’s Deorala village, women activists demanded a law that would not glorify the sati. In the case of Mathura, when in 1972 a tribal girl was raped in custody in Maharashtra, they demanded change that led to amendments about consent and custodial rape. The Bhanwari Devi case, in which she was gang-raped because she tried to prevent child marriage, led to the Vishaka Guidelines. “In the case of the pogrom of 2002 (in Gujarat), they demanded a law which said that rape within a sectarian strife will have to be dealt with separately,” Jaising said.

“All changes have come on the backs of these (grassroots-level) women. We owe them,” she added.

“When I was arguing the RG Kar case the most important demand the doctors had raised, which remained unanswered, is that we want our own elected bodies. That I would consider structural change,” she said.

The talk was organised by the Pratyay Gender Collective in collaboration with Kolkata Pride as part of its Kolkata Queer Arts Month programme.