He gave us plays, songs and ideas that are timeless. About, famously, a thief who has vowed never to lie, a tiger who refuses to kill, a sweeper woman who steals our hearts as she challenges upper caste authority by turning religious dogma and privilege on its head; also, retelling many a tall tale by the likes of Shakespeare, Moliere and Brecht.

During the century that has passed since his birth, Habib Tanvir and his many creations have become signposts of what is essentially modern India’s theatre ethos, telling us where we have come from and what we can aspire to. And as Kolkata Centre for Creativity hosted Dekh Rahe Hain Nayan, a three-day celebration of that legacy in the presence of artistes and theatre stalwarts, another name shone through the discourse _that of a certain Safdar Hashmi. Yes, the Communist playwright and theatre director who was murdered, while his group Janam was performing Halla Bol on the outskirts of Delhi in 1989, by a mob led by a Congress goon. Safdar sustained severe injuries, a result of around 20 blows to his head with iron rods. He died a day later.

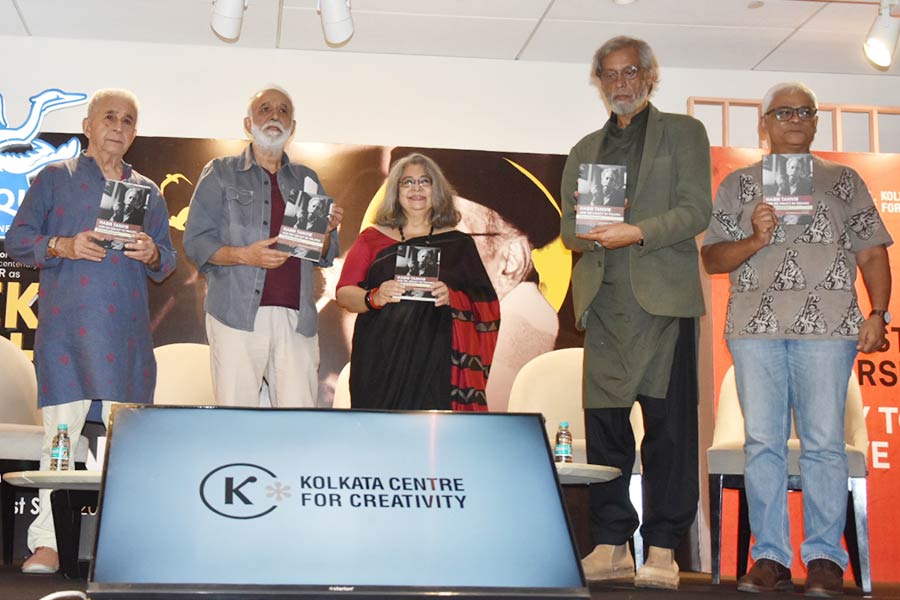

At the KCC event, two new books were unveiled. Habib Tanvir and His Legacy in Theatre: A Centennial Reappraisal, edited by Anjum Katyal and Javed Malick (Seagull Books) and Safdar Hashmi: Towards Theatre for a Democracy, authored by Katyal (Orient BlackSwan). Discussions, performances – Tanvir’s daughter Nageen sang songs from his plays _ a documentary film screening and an excellent book exhibition showcasing a constellation of like-minded theatre artistes, writers, filmmakers and their work, particularly Tanvir and his multifaceted devotion to a theatre that is fearless in ambition, secular in character and rooted to the pluralism that is at the core of India.

Safdar Hashmi got in peripherally, but naturally, because of what he stood for, the work he did in his short life and the kind of theatre his Jana Natya Manch continues to do. Tanvir also knew him, as a boy first __ he was the son of a colleague at the Russian Cultural Centre where Tanvir had worked for a while. By the time he was 34, and Tanvir 65, the two were working together. Guru and shishya. They barely had a few months together with the thespian attending Janam performances in the slums of Delhi, and Hashmi picking his brains on aspects of the craft that included writing in meter since songs, slogans and physicality were intrinsic to their productions. What a collaboration it was. If only it had not been cruelly thwarted, imagine what new peaks Indian theatre could have climbed.

Naseeruddin Shah, MK Raina, Anjum Katyal, Sudhir Mishra and Sudhanva Deshpande at the launch of the book, Habib Tanvir and His Legacy in Theatre at KCC. Amit Datta

“We were all in awe, initially at least. I was only 20 at the time, says Sudhanva Deshpande, actor, director and organizer with Janam. “And Safdar was already a guru and Habib saab a legend, a grand guru as such. That experience helped shape me fundamentally as a theater person,” says the author of Halla Bol: The Death and Life of Safdar Hashmi (LeftWord) that meticulously chronicles the vicious attack of 1989 and more. Why Sudhanva? Because he was there.

Tanvir's relationship with Safdar, his junior of 30 years, was completely democratic, recalls Sudhanva. “He used to listen to everything Safdar would say with complete attention, giving all due thought and consideration.”

The theatre they pursued was similar as it was dissimilar. Progressive social consciousness was at the core for both, reflected in productions that were energetic, vibrant yet thoughtful and reflective; at times, funny.

Safdar’s was street theatre. If he wanted to highlight, say, unfair labour practices and oppression, he would do it in slums, taking his message to the workers themselves with actors drawn primarily from the intellectually alive milieu of JNU and Delhi University. Tanvir worked with unlettered Chhattisgarhi actors, and after years of experimenting with Hindi, decided to perform in Chhattisgarhi, allowing them to improvise on situations dictated by the plays that were most often drawn from, and embellished with, elements of local cultures. This added a layer of festive exuberance to the performances.

In the context of today when there’s too much talk about India being “one” , Tanvir and Hashmi’s artistic consciousness stands against this diabolically unhistorical discourse that attempts to strike at India’s pluralistic roots. Both were committed to a form of theatre that foregrounds collaborations with the many Indias that unite India. “There are many Indias and every one of us has to engage with all these Indias,” says Samik Bandopadhay, theatre scholar and social commentator, agreeing that after a hundred years Tanvir’s legacy has come back as a charged, resonating, productive and creative memory.

Nageen Tanvir. Amit Datta

Consider why Tanvir decided to cast Nacha performers of Raipur (his birthplace) to act in Mitti Ka Ghoda, a Hindi translation of Shudraka’s Mricchatatika. See how Rahul Verma’s English play Bhopal, on the Union Carbide pesticide plant explosion and subsequent gas leak that killed or maimed over 365,000 people, becomes Zahreeli Hawa in Hindi and Chhattisgarhi with a preamble that weaves in a folk tale featuring a Baba Dev, along with a crab, crow, earthworm and spider, dovetailing Gond tribal mythology of Madhya Pradesh to incorporate contemporary ecological concerns about pesticides and MNCs.

Charandas Chor, the globally celebrated play about the honest thief who pays with his life because of his allegiance to truth, takes on many dimensions. Derived from Vijaydan Detha’s folktale-inspired story, the play turns an ordinary “chor” into a hero, beginning as it does with a dance by Satnamis who worship truth as God. As for his first play Agra Bazar (1954), the 18th century poet Nazir Akbarabadi, who offends Islamic conservatives with his popular (hence "vulgar") verse, is placed in a busy marketplace to illustrate the decline of Urdu poetry, all the while keeping the poet off-stage.

With all these innovations, Tanvir was helping us, the audience, engage with these local cultures that burst out of history, something he was able to pull off relentlessly throughout his life because of deep insights into the many Indias that reside within India. His politics was about addressing India through local realities that spring out of local histories and struggles. “So, grope into your own culture, delve into it, historicize it, read its politics and give it a form,” Bandopadhyay succinctly summarizes the key tenets of this inclusive approach.

Yet, Tanvir sadly remains persona non-grata for state-run institutions that exist to promote art and culture. Why? The documentary, Gaon ke naon Theatre, mor naon Habib, by Sanjay Maharishi and Deshapande, records an instance in September 2003 in Vidisha (MP) when the Tanvir-led Naya Theatre come under attack for staging Ponga Pandit, a play that deals with untouchability and intolerance in Hinduism.

Amid slogans of Ram, the audience is heckled and forced to leave the performance space. In the film, we see Tanvir trying to reason with the protesters: What are you doing? By all means protest and abuse if you have to, but don’t do it in the same breath as Jai Shri Ram! That day, Naya Theatre performed the play in an empty hall with only a few policemen present. “Here is a man with a Muslim name so steeped in the core values of Hinduism and its pluralistic ethos that it is clear he has internalized it," noted Despande, explaining why Tanvir and his oeuvre are real challenges for the right wing ecosystem to tackle.

Safdar, right from start, wanted political engagement with his theatre. It was a time, as Anjum Katyal notes in her book, when the youth were at the centre of potent political churnings in the world. Campus activism was making headlines with its kinship with Left idealism and joining hands with “causes” of the time, be it the feminism and women’s liberation, civil rights or anti-war movements.

After the Emergency was lifted, Safdar resumed work with renewed vigour. He realised, she writes, “Janam’s kind of theatre was an important part of the democratic process.” This meant Janam stayed focused on educating people and spreading awareness about their rights and responsibilities as citizens, all the while questioning and protesting injustice. That approach led to several plays, three of which are considered milestones: Machine (1978), Hatyare (1979) which confronted communalism and Aurat (1979) dealing with women’s rights. The street became Janam’s stage, offering at once low-budget easy accessibility to people, their audience. The street also offers an effective platform, especially in authoritarian times, to present an alternative point of view to the dominant mainstream narrative. The setup fits in with Safdar’s temperament of being against the use of art as a manipulative tool -- “It’s like taking someone by his collar and shaking him until he accepts your viewpoint. I’d rather appeal to the people with reasonable arguments and make them reflect about what’s going on.”

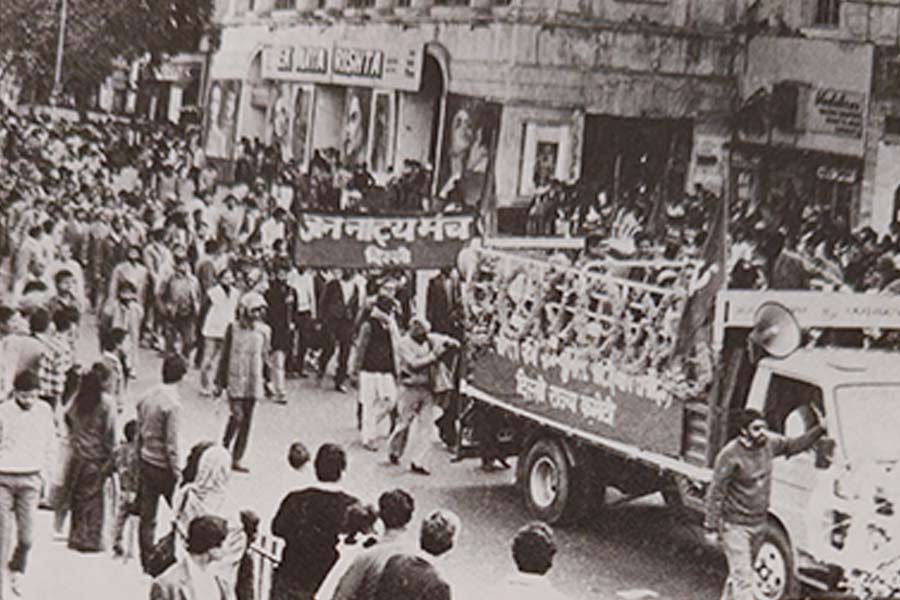

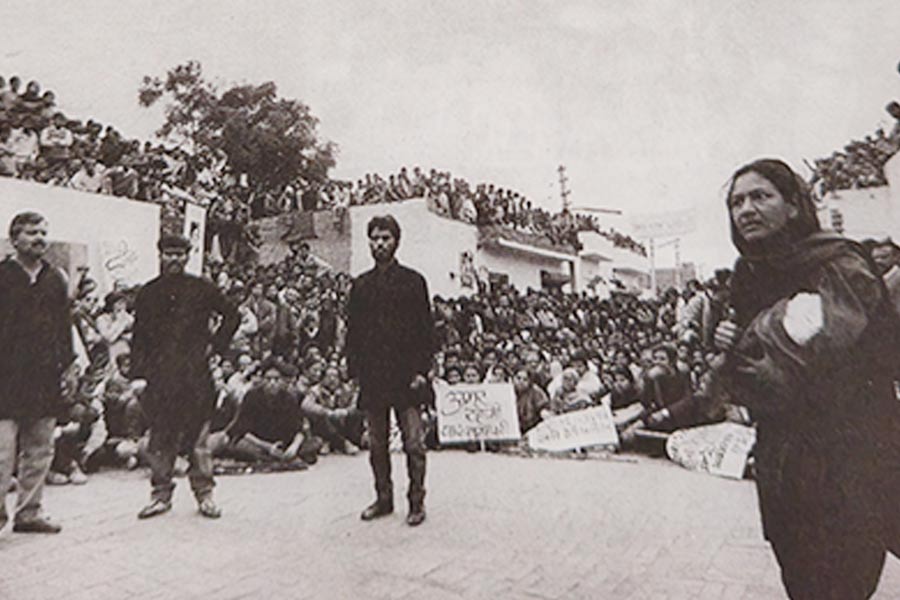

On January 2, 1989, a day after the attack, Safdar succumbed to his injuries. On January 3, over 15,000 people joined his funeral procession. The next day on January 4, Janam was back at Jhandapur, the place of the attack, to perform Halla Bol again. More than 5,000 people crammed the narrow streets to watch that performance of defiance. “End to police repression, to daily beatings and threats. We stand as one, we shall not rest till our demands are met,” the chorus chanted. A piece of history, local history, was created and etched in time. Today, 35 years since, we look back at that history as we create new histories of injustice; local histories springing to life here at home and afar.

THE DAY AFTER: The funeral procession, January 3, 1989. Picture Courtesy: Jana Natya Manch

IN THE NAME OF SAFDAR: Janam actors (from left) Tyagi, Jogi, Vishwajeet (seated), Brijender and Safdar’s wife Moloyshree, perform Halla Bol at Jhandpur on January 4, 1989. Picture Courtesy: Jana Natya Manch