Abanindranath Tagore’s paintings evoke the idea of India as a diverse cosmopolis, his great-grandson, a professor in California, said in Calcutta.

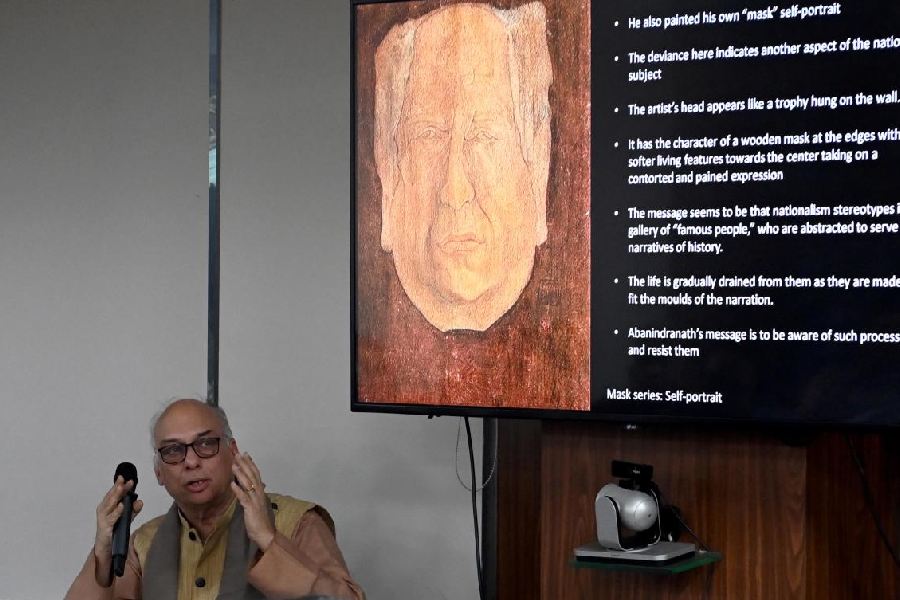

Debashish Banerji, Haridas Chaudhuri Professor of Indian Philosophies and Cultures and Doshi Professor of Asian Art at the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS), San Francisco, spoke on Abanindranath’s works at the Victoria Memorial last week.

He cited The Arabian Nights series, comprising over 40 intricate paintings based on medieval folk tales from West Asia that Abanindranath painted around 1930.

The series is a rich tapestry of medieval Arabia and colonial Calcutta. In the series, interspersed with characters from Arabian fairy tales is Jorasanko where the artist grew up.

“The Arabian Nights is assimilated into the Indian nation, its urban citizen-

subjects being asked to see themselves as belonging to its diverse cosmopolis,”

said Banerji.

One of the paintings Banerji spoke about from The Arabian Nights series was The Hunchback and the Fishbone.

Abanindranath’s depiction of the story is set in his local neighbourhood of Jorasanko. A tailor, his wife and the hunchback are the focus of the painting. The signboard of Kerr Tagore & Co, Dwarkanath Tagore’s failed enterprise, is part of the canvas. As is the Union Jack atop a building.

“Here, we are shown parallel diverse worlds.... At the same time, it is only at the highest level that one can see the Union Jack, the sign of coloniser or state power. At this level, the colonised is in affective dialogue with the coloniser, in a slippery interweaving of narratives aimed at inverting state control,” Banerji told the audience.

Banerji was delivering a lecture titled “Narrating the Nation through Paintings: Abanindranath Tagore’s Nationalism”, in the conference room of the Victoria Memorial Hall.

The lecture was followed by a guided walkthrough of Abanindranath’s paintings in an ongoing exhibition in the museum gallery.

Abanindranath (1871-1951), a nephew of Rabindranath Tagore and the younger brother of the artist Gaganendranath Tagore, was a transformative figure for Indian art and culture who spearheaded the revivalist movement that came to be known as the Bengal School of Art.

He was the vice-principal of the Government School of Art in Calcutta from 1905 to 1915. In his early years, he was trained in the Western tradition of painting. He went on to incorporate swadeshi values in his works, a pioneer at that.

At the height of the Swadeshi movement, the Bharat Mata painting established Abanindranath as the leader of the nationalist movement in art. On Thursday, Banerji talked about the work in detail.

Iconographically, the painting is based on Buddhist goddess Vasundhara, the deity of

fertility and prosperity. But the Bharat Mata painting deviates from Vasundhara in replacing opulence with austerity.

“It is a renunciant image instead of an opulent one in keeping with the need for concentrated austerity during the freedom struggle,” Banerji said.

Abanindranath was backed by the founders of Indian art history, like Ernest Binfield Havell, the British art historian and administrator who worked in India in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and Sister Nivedita, the Anglo-Irish social reformer.

“They were invested in an idea of India based on a history of art... The place of art in nationalism is to inspire a connection to the nation as an idea, an identity based on an origin, a history and a telos or goal,” said Banerji.