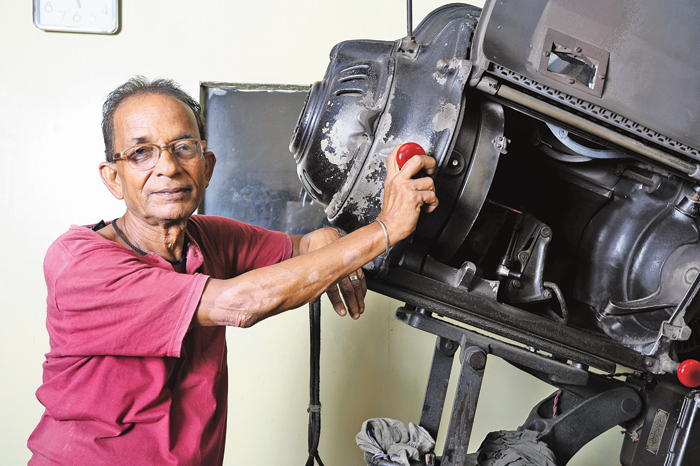

Sukumar Ghosh cycles every day for two hours from Sonarpur to the theatre in Bhowanipore, travelling a distance of about 20km, carries his bicycle up the stairs to the third floor and parks it in the projection room. He has been doing so for the last 41 years. He is the projectionist at Basusree theatre in Bhowanipore, and comes to work 365 days a year. Though the projectors do not work anymore, they are his life.

The film Dream Girl can be glimpsed on the big screen through the rectangular holes of the projection room. The theatre only has a handful of people. Sitting here, Ghosh has seen the shift from film to digital and cinema changing forever.

Now around 65, Ghosh, a small wiry man with a smiling face, has spent most of his life inside a theatre. He was in his teens when he was employed as an usher in a small theatre in Sonarpur. He was asked to help two women ushers who were in charge of the “Ladies” section of the theatre. “I still remember their names: Meera Goswami and Parama Pathak. But you don’t need such details,” he says.

Soon Ghosh, a bright boy, was promoted to a room above and initiated into the mystery — also in the medieval sense of the word, which meant a profession — of the film projector. It was a discipline in itself.

The projection room was then the nerve centre of the theatre. The projector was a grand piece of work, a thick-set machine that stood above human heads, its finely-tuned elaborate parts running the film. Reels needed to be changed deftly, without delay. The sound had to be synchronised with the images. If there was one glitch, the audience would protest. Film projection required great skill. But the projectionist at the Sonarpur theatre thought Sukumar would be up to it.

And he was. In a year he was even managing shows on his own. Then came his big break: a projectionist’s job at Basusree cinema in 1974.

Basusree then was a different place. The theatre, founded in 1947 with a grand staircase inside, had a glorious past: Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali had released here in 1955. Ritwik Ghatak’s Ajantrik was premiered here. For the event the car had been pulled up to the upper floor. It had screened several other landmarks of Indian cinema through the Fifties and Sixties.

When Ghosh joined, it had a glamorous present: blockbuster Hindi films, featuring “Dharmendra, Shashi Kapoor and Bachchan”, were being screened here, says Ghosh.

But he got sucked into another kind of action. The projection room had its own intense drama.

The process was elaborate and demanding. First, the reels would have to be managed.

A film could consist of 20 reels. Basusree had three projectors. To ensure smooth transition from reel to reel, the projection would have to be co-ordinated between the projectionists and their machines; as soon as one reel ended, the other one had to start. The ends of the reels would be marked by projectionists to signify it was about to end. Different projectionists had different signatures. Ghosh shows his marker. It would leave an imprint of round shapes on the film.

Second, a film’s reels could be reserved for a theatre, or they could be moving between theatres. If one film was being shown at different theatres, different teams of men would be running between theatres with different sets of reels. Once the first two reels were shown at the first theatre, one team would carry them to the second theatre, to bring it back to the first before the second show.

On release day, the projectionists had to come before the show to check the reels. Ghosh became a pro. “I didn’t have to look at the screen. I had to run the film through my fingers or just listen to the projector’s sounds. I would know something was wrong.”

Unlike the boy in Cinema Paradiso, Ghosh was not much concerned about what showed on the screen. He was captivated by the projector. He had no other life.

“I remember Do Anjane was shot here with Amitabh Bachchan and Rekha. I didn’t see much, except Rekha running into the theatre and collapsing on the aisle, against the screen showing the sign ‘Intermission’,” says Ghosh after some thinking. But he was thrilled when he showed that scene on the screen.

Five projectionists manned the show at Basusree. But no one worked on all shows, as that was prevented by law.

“The projector machine emits carbon. A projectionist needed a licence to work. Too much exposure to the projector often resulted in projectionists suffering from TB,” says Ghosh.

The digital age has eliminated the people, both from the theatre and from the projector room. Ghosh points at the small digital projector inside an air-conditioned enclosure in the projection room. “Our work was such hard labour. This makes us lazy,” says Ghosh.

Digital projection began around 2002 in the city. In 2007, it had replaced the old film projector. No one lost their jobs in the Basusree projection room, but they had lost their work.

Three have retired. Two of the projectionists are still to be found in the projection room, along with a younger man who is the digital projectionist.

“I can only thank the management for not taking our jobs away,” says Ghosh.

The current Basusree owners also take pride in the projectors.

“People stopped coming when every film was being showed everywhere. Also, here they cannot get the food they get at a multiplex,” says Ghosh.

One of Basusree’s current owners, Saurav Basu, calls the multiplex experience a “picnic”. He says how difficult it is to sustain an old world, single-screen theatre now.

But the show will go on. As will Ghosh.

“The projectors remain in top condition. This is the upper magazine box, this the projector head, the sound head, the lower magazine box. This is how it works,” he says, starting one projector.

But the machine does not start. Ghosh is embarrassed. “It’s the sulphate because of the rains,” he says. It will be corrected. Because his job is now to look after them.

He will cycle his way back home to Sonarpur in the evening, to return again next morning. He does not take a day off.