There is a saying in Bengali that goes — Churi bidya mahabidya, jodi na poro dhora. Meaning: thieving is high art, provided you are not caught in the act. Of course, mahabidya, as purists understand it, is a different ball game altogether.

In these times of highly specialised crime and criminals, thief — sans prefix — sounds more like a sharp reprimand rather than a social threat. But there was a time when the thief basked in literary limelight in Bengal.

It is perhaps not incorrect to say that Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay has been the champion of the endearing chor in children’s literature in Bengali. Says the novelist and short story writer, “My father was employed in the Indian Railways. This meant we spent a fair bit of our lives in the countryside, in the mofussil. My stories and characters are born of that experience; the chor is no exception.”

There are many levels of thieving.

There is he who steals from the householder in the countryside by digging a hole in the wall of his mud hut. He is the sindhel chor. Then there is he who makes away with the most insignificant of objects from a house or a person. He is the chhinchke chor. A thief who cheats another thief is a baatpaar. And a thief who resorts to trickery is a jochchor.

Sudraka, the fifth century playwright, has written about the qualities of a petty thief in the Sanskrit play, Mricchakatika. Sudraka writes that a thief must be as soft-footed as the cat, as nimble-footed as the deer, as keen of gaze as the eagle, as keen of sense as the dog and as slippery as the snake. In the play, which is really about the common man and his travails in love and life, the thief boasts, “I can assume any form, perform magic like the best of sorcerers; I am a polyglot too; and I can move like a horse on land and like a boat in water.”

Bengal’s folklore is replete with details about the petty thief’s ingenuity. How he prowls in the dead of the night slathered in mustard oil — and carrying enough on his person — to quite literally give his captors the slip. This is also why he wears scant clothing and wears his hair in a very close crop.

The chor, be it of Rajsekhar Basu’s creation or Leela Majumdar’s, Sanjib Chattopadhyay’s or Mukhopadhyay’s own, comes suffused with pathos mixed with humour. And it would not be an exaggeration to say that what comes between the thief and the stick is the readers’ sympathy. One rarely comes across a story where a thief is handed over to the police or beaten to pulp.

Mukhopadhyay tells The Telegraph of his preoccupation with the chor, “No, I have not known any personally. But the writer should always take the side of the person who has lost the battle with life.” Mukhopadhyay and his ilk’s sympathy for the chor imbues the portraitures, and the sympathy becomes part of the characterisation of the chor — of his skeletal form, of his voracious appetite, of his propensity to faint in a crisis. Depending on individual style, the writer will emphasise the thief’s condition either with humour or stark telling. Oftentimes, even when caught red-handed, the thief is let off only with a boxing of the ears and a haanri of sweetmeats for the road. At other times, an indignant thief will return to his victim stolen goodies et al, only to have the latter know that the items he made away with were of unsatisfactory quality.

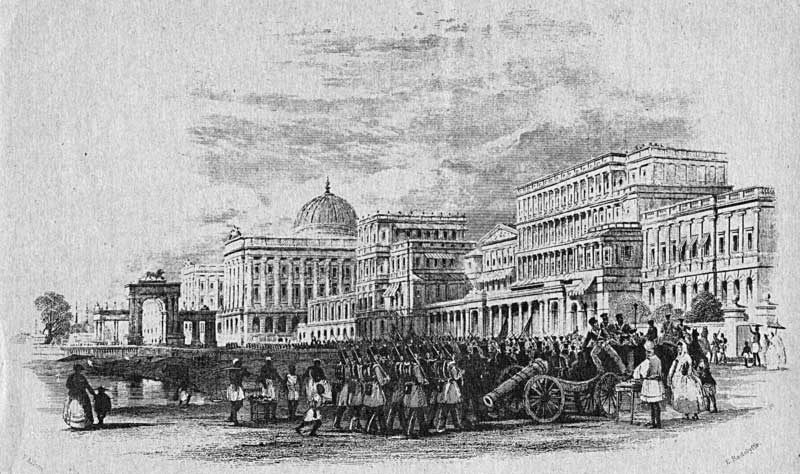

This sympathy and indulgence of the writer and reader most likely stem from collective social guilt. In the paper, City of Dreadful Night: Crime and Punishment in Colonial Calcutta, historian Sumanta Banerjee explores the why. He talks about how in the late 18th century, the East India Company started to clear the agricultural areas of three villages — Sutanuti, Dihi Kolkata and Gobindapur — to turn them into a city and how this ended up ousting a good many from their homes in the countryside of Bengal.

Banerjee writes: “…a large number of the city’s unorganised poor precariously scraped a livelihood by means that were often ignoble and furtive.”

The chor’s foil is not his victim but his more robust country cousin — the dacoit. The dacoit who announces his arrival, while the petty thief slinks about. The dacoit who is flamboyant, while the petty thief is near invisible, must be inaudible too. The dacoit who is feared and notorious, while the petty thief is endearing and pitiable. Says Mukhopadhyay, “My chors are mostly driven by hunger — a perennial problem in our socio-political scenario. And yes, many of them have attained a mastery over their craft.”

Banerjee writes about sindh-kata that involved a patient boring of a hole or sindh into the wall of a house with the help of a sindh-kaathi or iron crowbar. He writes, “Once the hole was wide enough to allow the sindhel (house-breaker) to crawl his way into the room, he managed to loot whatever he could lay his hands on, pass on the loot through the hole to his accomplice (who used to wait outside to alert his comrade about police patrols), and then escape back through the same opening.”

That committing theft requires art is evident from an olden Sanskrit sloka, which basically describes the shape of the sindh or hole bored by the thief. According to the unattributed sloka quoted by Manoj Dash in his book titled Banglar Chor, those shapes would be a lotus in full bloom, the rising sun, the scythe-shaped moon, a rectangular pond, the swastika and the pitcher.

According to Banerjee’s research, while the gang-robbers and river dacoits found themselves paling into oblivion from the Calcutta police records towards the latter half of the 19th century, “earlier crimes like murder, petty thievery, cheating, counterfeiting and receiving stolen goods continued at an unrelenting pace”.

By the 1870s, lock-breaking had replaced the art of sindh-kata and then the railways spawned fresh genres of thieves. Leela Majumdar writes about the thief waif hanging precariously from the window grill of the ladies’ compartment whining to be let in. Banerjee writes about the “Burwars”, who were known for travelling by train and alighting at wayside stations with the luggage of sleeping passengers. He also writes about the “Bhamptas”, who carried out their business under the benches in third class railway compartments and cites the case wherein one lifted the Governor of Bombay’s travelling bag “from brilliantly lighted saloon on the Southern Marhatta Railway, under the very noses of a strong body of police escorting the train”.

In Mukhopadhyay’s writings the chor is a benign presence, a deviant do-gooder, waiting to, wanting to, yearning to embed himself into the social fabric once again. Says Mukhopadhyay, “My thieves are overall good human beings, committed to social service. They are also very emotional. What I want to convey is that this league of petty thieves of rural Bengal should never be deemed abominable.” The writer goes so far as to say that petty thieves are any day better than those who make a life and living out of exploiting others.

And you still think it is abhorrent that a thief should run away with Tagore’s prized Nobel? He was merely taking things very literally.