On this day 30 years ago, our neighbour from AL Block Ashis Hazra was on a Swedish icebreaker ship headed to Antarctica. The scientist spent the winter of 1989-90 (in Antarctica this is peak summer) conducting experiments on the white continent as part of India’s ninth expedition there.

Now an emeritus scientist, former additional director of Zoological Survey of India (ZSI) and a core committee member of the government’s Antarctic research, Hazra shares his experience with The Telegraph Salt Lake:

Ship that breaks ice

Back in the day, during a ZSI meeting, I had proposed that our department send a team to Antarctica. Our director loved the idea but everyone else backed out at the thought of actually going there. So I was chosen to do the job.

The Indian expedition had 81 people — scientists, members of the army, navy, air force and doctors. We set sail from Goa and headed southwest on the Thuleland, a Swedish ship that was so huge it would stretch from City Centre to Sector V!

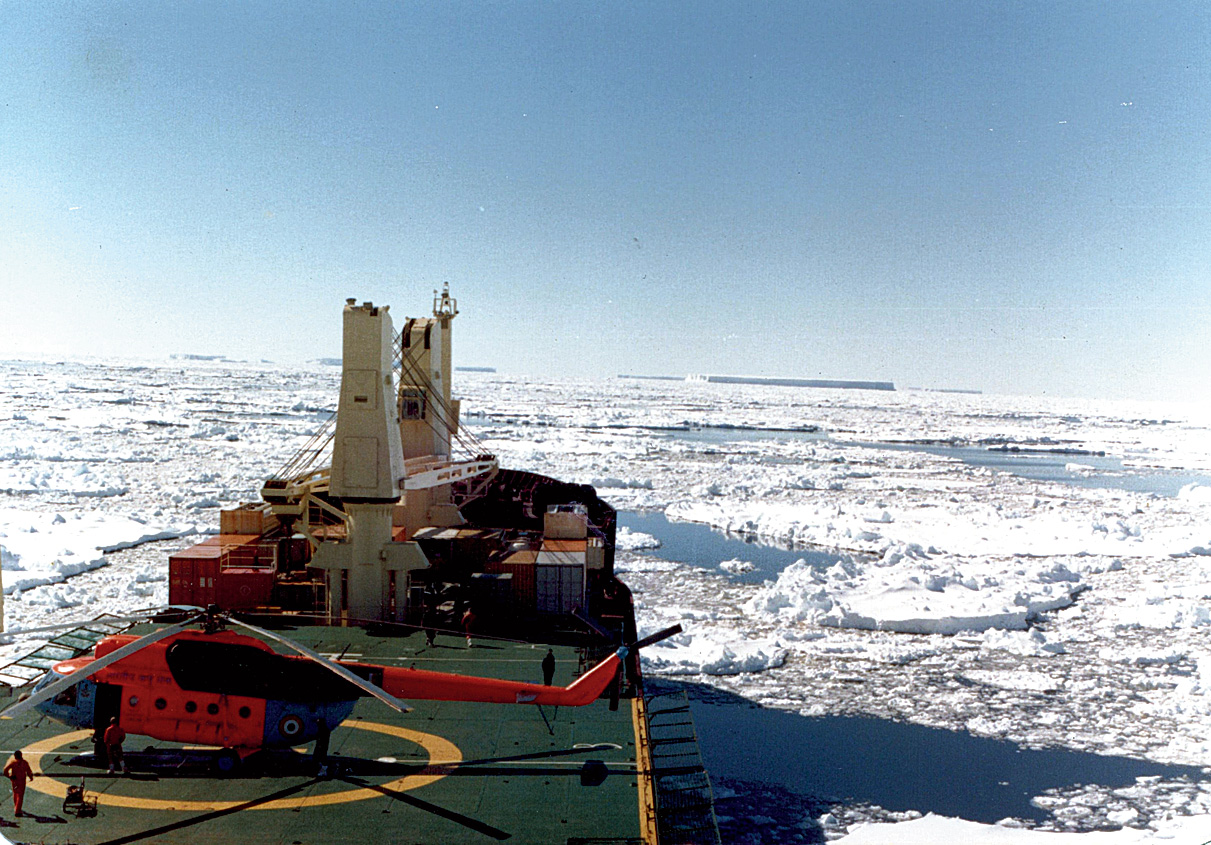

As we crossed the 51st parallel south latitude, we started encountering what looked like sheets or boulders of ice on the water. Sometimes we could witness the water turning into ice and approaching the ship! While it looked harmless, nine times of what was visible lay hidden underwater and we had to dodge it, lest we did a Titanic.

When the ice got too much to dodge, our ship would deploy machines to break the ice and push its way through. But when the icebreaker could move no further, our air force pilots brought out our Mi8 helicopters and flew our team to mainland Antarctica.

Centre lost under snow

Antarctica is abundant in minerals like coal, gold and oil and so many countries want to claim it as their own. So an Antarctic Treaty was formulated in 1959 in which member countries agreed that it would be no man’s land. However they are free to go over and conduct peaceful and eco-friendly scientific research.

When India reached the continent in the early 80s, they built an ad hoc research centre near the eastern shore and called it Dakshin Gangotri. But within weeks of our stay there, it got drowned in snow and we had to move into a new station — Maitri — in a rocky part of the continent that continues to be used.

Drinking molten lake water

On paper, Antarctic summer means sunlight even at night, but in reality the sun shone bright just once or twice a week. The rest of the time it was stormy, with low light.

Blizzards, at speeds of up to 200kph, were common. They would make our huts tremble and leave so much snow around us that we would have to shovel our way out of our huts every morning. But this snow would not fall from the sky like rain. It doesn’t rain in Antarctica. The blizzards lift loose snow or ice from the ground and blow it around.

When we reached the continent, the temperature was -2°, although up to -89° has been recorded there. Humidity would sometimes slip even below 2 per cent and oxygen level was low as there are no plants to create any.

We lived in prefabricated huts, where the ground floor was our lab and first floor was the living area for three or four of us. We ate packed food, drank water melted from an adjacent lake (that we named Priyadarshini after Prime Minister Indira Gandhi) and were flown to the ship once a fortnight for a bath.

The ship kept sailing in the vicinity for the months that we did our work and since the choppers had no helipads to land on the ice, we would climb in and out using ladders dropped down.

Protective papa penguins

We had a lot of zoology work to cover on the trip but everything depended on our colleagues from the meteorology department. They would release weather balloons every hour to predict storms and we would have to plan our excursions accordingly.

Since the land has snow whichever way you look, one has no visual reference to navigate. This is a condition called “whiteout”. To help us find our way, we would plant “colour sticks” for up to 4km outside our centre. And if we needed to cover an extra mile tomorrow, we would have to go today and plant extra sticks.

On the work front we got to study plant and animal life. We found moss, mites, nematodes and springtails and are still studying how they adapt to the inhospitable conditions.

We studied albatross, huge birds with wingspans of 12ft, and skuas, predatory birds with webbed feet. They do not have perching claws like birds in Calcutta as there are no trees in Antarctica for them to perch on. Rather, they have webbed feet that lets them swim and eat krills, a shrimp-like creature that supports most of the food chain on the continent.

The most fascinating birds were the emperor penguins. These are the largest penguins — about 5ft in height and over 30kg in weight — and are the only birds that lay eggs in winter.

A female lays a single egg in April, hands it over to her mate and heads to the ocean. She feeds there for the next four months while the male incubates the egg in a pouch above his feet. He stands still and goes without food; and in case of strong blizzards, huddles with other males to protect their eggs.

The females return in August when the eggs hatch. Penguin colonies have lakhs of them living together but a couple recognises each another by their distinct voice calls.

The male now transfers the chick to the mother’s feet and heads to the sea to feed. The mother regurgitates part of what she has eaten all winter and feeds the fledgling. Penguins mate for life and the couples will continue this cycle every year.

As per the Antarctic Treaty we aren’t allowed to take any live animals out of the continent but I brought back a penguin chick that had died, a spoilt penguin egg…. They are on display at the ZSI museum in New Alipore and the Indian Museum.

Death & disease

One of our team-mates got appendicitis but the doctors were not worried. Antarctica is too cold even for bacteria so they removed his appendix without any fear of infection.

Before heading out on this trip we underwent intense training. We were made to sign a government bond and told in unambiguous terms that there was a 50-50 chance of survival in Antarctica. Little did we know that four of us would, indeed, not be returning home.

On January 8, three scientists and a naval officer were found dead in a tent they had erected for research 70km from our centre. It was probably due to carbon monoxide poisoning from a generator they kept in their tent to run a heater. They knew generators weren’t allowed in tents but perhaps the cold was unbearable.

We were very upset, as were the Russians who came down from their station to offer condolences (with the help of dictionaries).

Usually bodies of those who die in Antarctica are left there as a lasting tribute but we wanted to send our friends home. We kept the bodies in coffins and a month later a Russian plane would carry them back.

But so punishing was the weather that when the plane arrived, we couldn’t find the coffins under the snow! We had to get a bulldozer to do the job.

Antarctica holds 90 per cent of the earth’s ice. This is why global warming is such a concern. If all that ice melts, imagine how much the sea level would rise and how much of the rest of the world would get submerged.

The place is pollution-free but ironically the ozone layer above it has got a hole. We can draw political boundaries across the earth but pollution does not abide by it. People in Europe and Asia could be using excessive air-conditioners and fridges but the effect is showing in the South Pole.

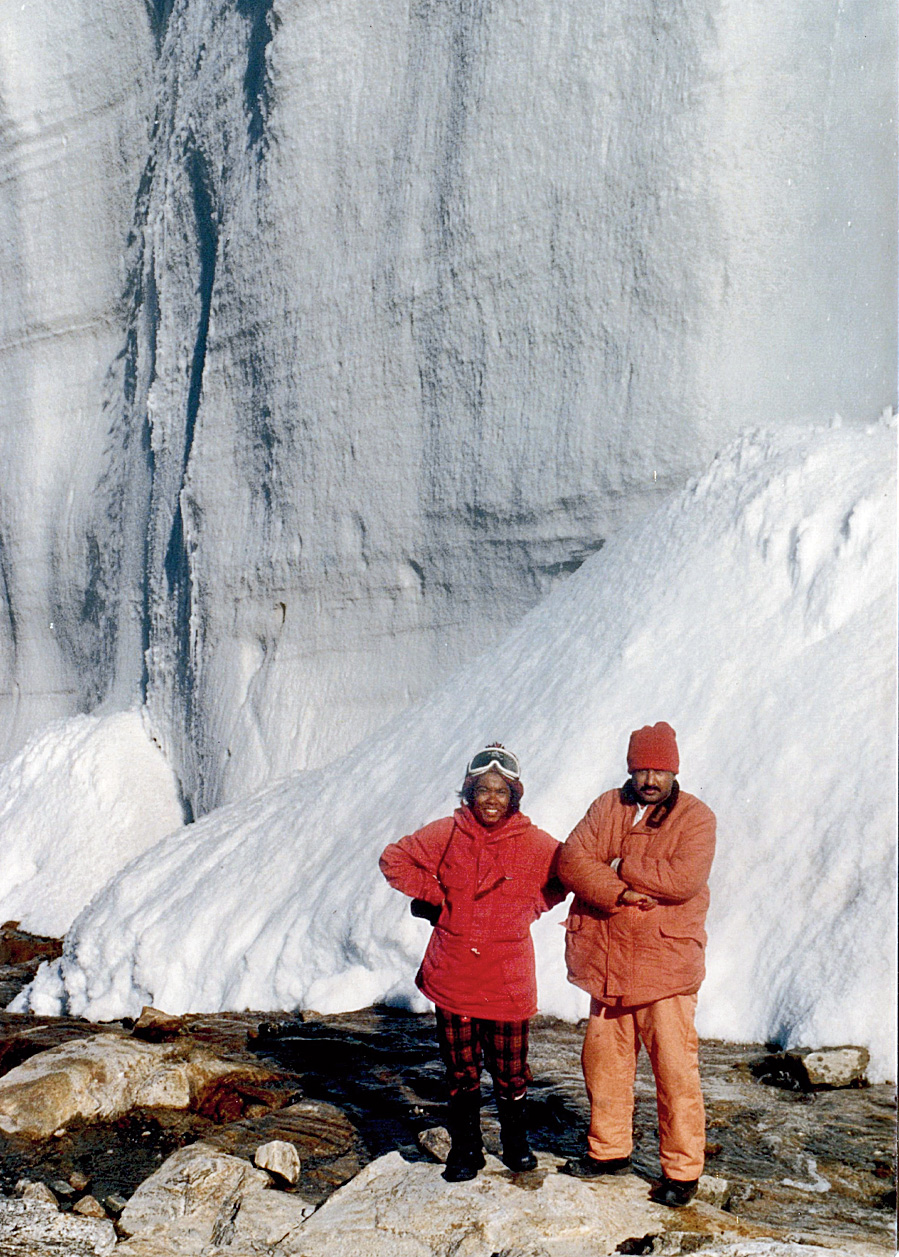

Hazra with teammate and geologist Sudipta Sengupta. The Telegraph picture

Due to a superstition, passengers of a ship crossing the Equator were to enact a play seeking permission from the sea king and queen. The Telegraph picture

Thuleland, the Swedish icebreaker, veers it way through icebergs. The Telegraph picture