Neighbours walking by DL Park can spot Amitendranath Tagore hunched over his study table in the ground floor of his two-storeyed house. The grandson of Abanindranath Tagore turned 98 on October 9.

“People come to see what it is like to be in the 90s. It’s just my knee that bothers me. I need a stick to walk these days. I used to walk so much in the park. I can’t do that any more,” he says, opening the door himself to let in The Telegraph Salt Lake.

But that does not deter him from either visiting City Centre to buy shoes or Santiniketan for Pous Mela. “I will visit Pous Mela as long as I live. Bhola drives me everywhere in our car,” he says, referring to his Man Friday who has been with him ever since he returned from the US in 1987.

He had spent 19 years teaching Chinese at the Oakland University in Michigan. “The food there was fresh,” he reflects.

On his return, he had settled in CL Block in a rented house with parents as his DL Block house was being built. “CK Market was so dirty.” The mention of market makes him complain about rising prices of daily necessities.

Watching and reading the news takes up much of his time. “I take my bath by 8am and come down from the first floor. I love to follow different interpretations of the same news involving Modi or Didi by different newspapers,” smiles the man who has not ever missed casting his vote.

He is upset at recent reports of Kala Bhavan students singing the Rabindrasangeet Sedin dujone dulechhinu boney in an altered tune and a disrespectful tone at Nandan Mela.

“Kala Bhavan and Sangeet Bhavan are the heart of Visva Bharati. How can they do this!”

The knee pain reminds him of his grandmother Suhasini Devi. “When I was about four or five, she used to ask me to tell tales of the epics while I massaged her feet. The day I finished the story of The Ramayana our kajer didi touched my feet and offered me sweets on a plate. I was taken aback,” he recalls.

He has vivid memories of his grandfather. Abanindranath Tagore had a water tank which was kept full for his bath. Children were barred from venturing near it. “That aroused my curiosity. One day, I climbed the side and was leaning in from the waist when Dadu dragged me down by the drawstring of my pyjama and pulled me upstairs to Ma, shouting: ‘Parul, Parul. See what your son has done. He was almost drowning!’ Then he buckled me to the railing of the verandah with the chain of our dog Bhalu who was playing downstairs. I was stunned that Dadu could tie me with the dog’s chain.”

This incident took place at Tagore house no. 5 in Jorasanko where his childhood was spent. “Dwarakanath Tagore had built it to entertain his clients of Carr, Tagore & Co. Much of it has been demolished. Rathindra Mancha stands where our garden was.”

He has faint memories of Rabindranath Tagore too. “Rabindranath was fond of mangoes. When he came to Calcutta, he would send word and my mother would visit him at house no. 6 in Jorasanko with mangoes. I would climb up the stairs clutching the anchal of her sari. He would say;” Oi dyakho, Parul abar aam enechhe,” and ask the attendant to serve the fruit to everyone.

He loves to read accounts of Thakurbari and has got Bhola to buy him some books on the subject. And when memory fails him on little details, he looks up his autobiography Amit Katha which is kept on his table.

He murmurs a song to himself with curious lyrics. “Makorta (makorsha or spider, he explains later) phul boney khasha boney jaal/ Pokamakor lotke pore, machhi paley paal).” A mischievous twinkle appears in his eyes when asked about it. “I was singing this in front of my Santiniketan home when Mohan Singh, who used to teach music there, was cycling by. He stopped to say this was set in raga Moru Behag. I had once bragged to Santida (Santideb Ghosh) that he might have learnt singing from Dinendranath Tagore but I had learnt a song from Arunendranath, Dinendranath’s uncle. This is that song.”

He used to be a regular at block programmes till some years back. “Now I am old and they don’t call me.” But he always goes to the pandal during Durga puja. “I go to check if they have placed the mouse at Ganesha’s feet. Once they had missed it and I had raised a ruckus. How can they miss the mouse when they never miss Kartik’s peacock?”

Santosh Kumar Ganguly: Age: 94 years (CK Block) Picture by Saradindu Chaudhury

He turns 95 next month but to everyone in the neighbourhood — including those of his grandchildren’s age — he continues to be the endearing “Ganguly da”.

Even those outside CK-CL Block are likely to have seen him on stage; once a radio artiste, he still performs. A childhood friend of Uttam Kumar’s, Santosh Kumar Ganguly loves chatting and recounts the story of his life with great gusto.

“My annaprashan took place at Uttam Kumar’s house,” says Ganguly. “We lived in Bhowanipore and his mother — Chapala mashi — and my mother were great friends. I was a year or so older than him.”

Ganguly’s family ran a clothes shop at New Market and he himself was a gifted singer. During college, he started performing on All India Radio, from 1943. “Those were the days of Manabendra Mukherjee, Shyamal Mitra….” It’s also through the radio that he met his wife Bani, who will turn 90 on January 1.

Bani joined the radio station as singer a few years after Ganguly. “When her father learnt that we lived in the same neighbourhood, he asked me to escort her to and fro. Soon, her mother initiated our marriage.”

Ganguly is said to have been a handsome man. “Uttam would joke that if Bhutoda (my nickname) entered films, he would not have become Uttam Kumar,” he laughs. “Uttam was a wonderful person, helpful and humble. In my opinion Nayak was his best film, but not just for his performance. It was the story of his life.”

At the insistence of his parents, Ganguly pursued a career in accountancy instead of music. The couple had two sons and moved to Salt Lake in 1984, post retirement. “After the hustle and bustle of Bhowamipore Salt Lake seemed lifeless; we would hardly see any people around,” he recalls.

Out of loneliness, Bani founded the ladies club of CK-CL blocks with about 10 members in 1984. The club is still active and the December meet is scheduled to be held at her house. Though her mobility is restricted now, Bani still trudges along with a walker, managing the household, haggling with helps. “I was also the founder-secretary of All India Women’s Conference (AIWC) Salt Lake Sector II branch,” she smiles.

In 1984, some neighbours got together and formed the CK-CL Block committee with Ganguly as vice president. They held a puja that year with seven neighbouring blocks. In fact, Ganguly was president of the committee till as recently as 2016.

The couple now lives with their elder son and daughter-in-law. “Baba has never been disciplined about food or sleep,” says son Gautam. Indeed, on Sunday, The Telegraph Salt Lake found him slurping chowmein for breakfast!

Healthwise, Ganguly has blood sugar, allergies and had broken a leg a few years ago. At present, he’s excited about his upcoming birthday. “In 2020, my birthday — January 29 —will be on Saraswati puja. Just like it was in my birth year 1925,” he smiles.

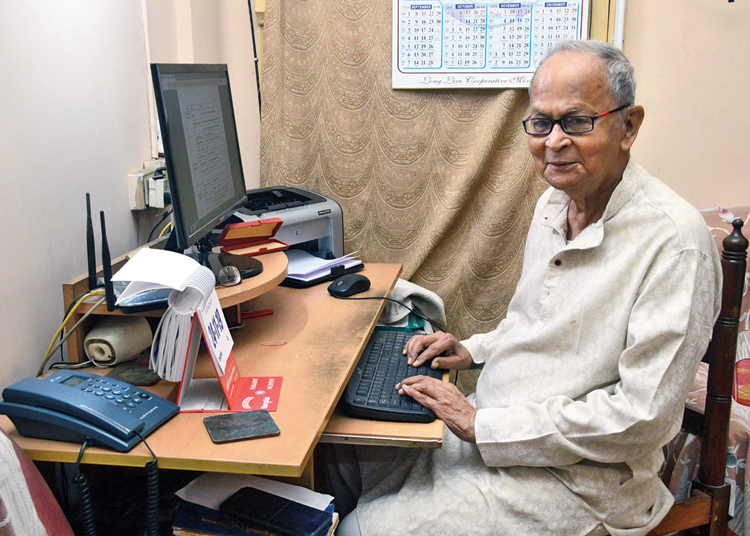

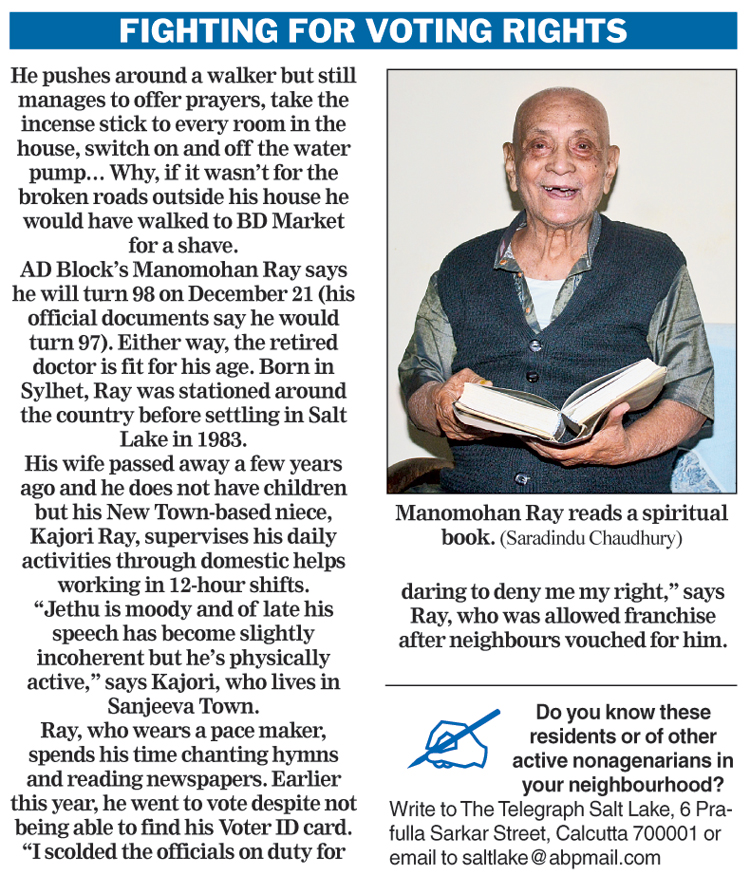

Bhattacharjee types out letters and takes printouts Picture by Saradindu Chaudhury

On his 94th birthday last month, Ratish Ranjan Bhattacharjee took a flight to Assam. It was the reunion of Oil India’s Old Boy’s Association so he, the senior-most member, had double the reason to celebrate.

On November 29, Bhattacharjee turned 94. An active member of nearly 10 organisations, he is as engaged as one can be. “People ask how I kill time. I tell them I wish there were 48 hours in a day so I could get more work done!” he smiles.

Bhattacharjee is regular on WhatsApp and Facebook, and doesn’t understand what the big deal is. “People of my generation have either passed away or got bed-ridden so if I want to make friends I have to speak the language of 60-year-olds,” he reasons.

Bhattacharjee is associated with professional groups like the Institute of Engineers and social ones like Paritosh Sen Memorial Elderly Care Society. He goes over in the afternoons, composes letters for some of them, types them out on his computer and takes printouts on his own.

The secret to good health, says Bhattacharjee, is to be content with what one has. “It doesn’t matter if your neighbour buys a 40 inch TV. Be happy with your 24 inch one. Today I can proudly say that I owe none a penny. I am happy.”

On TV, Bhattacharjee watches the news and cricket (he enjoyed the pink ball day-night Test format), and turns to YouTube to watch films. Amanush, Antony Firingee, Dadar Kirti and Sholay are his favourites.

He also is a good orator and at cultural programmes performs audio drama, and recites Tagore and Nazrul. “The first poem I learnt was Nazrul’s Daridro, in school, and I still remember it by heart, along with 10 per cent of Tagore’s Sanchaita.”

His only major health issue is that he is hard of hearing but hearing aids take care of that. He lives along with a full-time domestic help. “Dadu would drive till about five years ago. He would take me to CA Market to refill supplies,” says the help, Minu Mitra. “Now he Ubers.”

Bhattacharjee was born in Silchar, Assam in 1925. His father was in the postal department and he was one of seven siblings. A bright student and sportsman, he played cricket, football and won prizes for swimming across the Brahmaputra.

He graduated as an engineer and joined the then-British army on short service commission in 1943, during World War II.

After leaving the army, he moved to Digboi, the flamboyant town in Assam where oil had been discovered.

He remembers gathering with others at a field on the night of August 14, 1947. “We heard Nehru’s speech over radio and women blew conchshells at the declaration of our independence.”

But he had to leave the state and move to Calcutta in the aftermath of the Bhasha Andolon. The family moved to Behala initially. “By the 80s, we had acquired this flat in Vidyasagar Abasan. We moved in but only after a VIP resident stayed here first.”

In 1982, the Congress party held a session in the city for which Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was put up at what is now known as Indira Bhavan. “They needed space to put others up but Salt Lake had next to no infrastructure then.”

Party members learnt that Vidyasagar Abasan had two vacant flats — one of them Bhattacharjee’s. “So senior party members Atulya Ghosh and Priya Ranjan Dasmunsi wrote to me asking if I would let out the space. I happily agreed and without any charge. The person who stayed at my flat was the young Turk of Congress who would later go on to become Prime Minister — Chandra Shekhar. In fact I later wrote to him when he became PM and he replied, acknowledging his stay at my flat,” says Bhattacharjee proudly. “The letter must be somewhere... My wife would keep them well.”

His wife Minati passed away of a heart attack in 1991 at the age of 65. “I miss her but her death was a blessing. She died healthy, without suffering and without being a burden on anyone. People say they are waiting for me to turn 100 but I tell them I want to go while I am still on my feet,” says the man who was once 6ft but now stands at 5.11”.

The Telegraph