Manipulative disinformation, including deepfakes, is increasingly becoming the main problem for poll panels across the globe.

Members of election management bodies spoke about these challenges during a two-day conference here that concluded on Friday.

On the sidelines of the Global Election Year 2024: Reiteration of Democratic Spaces, Takeaway for Election Management Bodies (EMBs) conference, Kazakhstan’s central election commission chairman Nurlan Abdirov told The Telegraph: “It is most important to first define what deepfakes are, for which we would require scientific study. In my personal opinion, we need algorithms to quickly and professionally detect deepfakes in future, and help people identify deepfakes.”

He added: “The task of an election management body is to identify the motive for the deepfakes and then to tackle them. We must inform local officials and the general public how to do this…. Deepfakes will also push politicians to be transparent, for example, to show their families and the environment they live in to prevent disinformation being spread about them.”

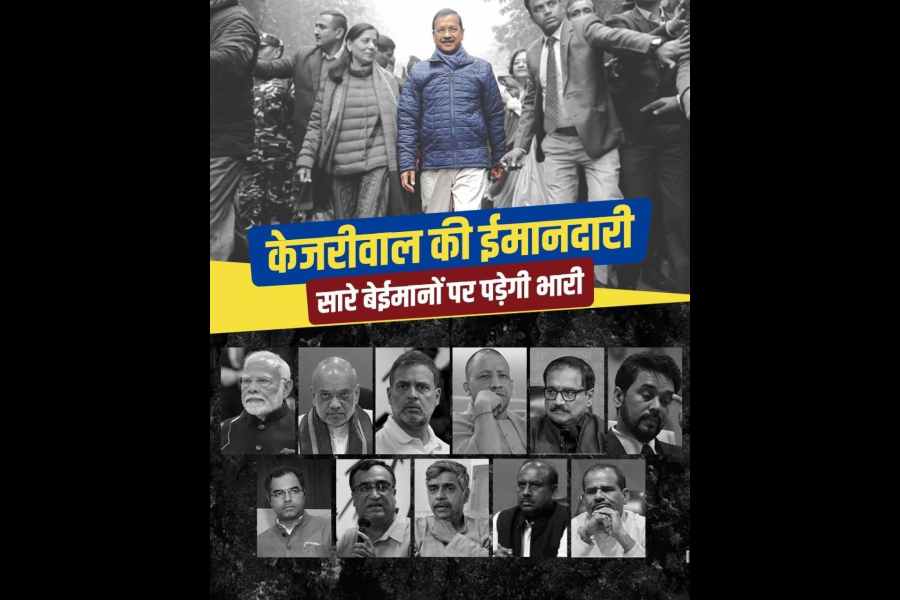

AI-generated audio, still images and videos that spread disinformation are a rash now and have upset the level playing field in several countries.

Kazakhstan’s polls were previously criticised for being undemocratic. However, in 2023, the ruling Amanat party was reduced from a super majority to a simple majority for the first time since 2004 in the Majilis — the lower house of Parliament. Newer Opposition parties gained strength in these polls, the first after the Bloody January protests of 2022.

Anusuya Shanmuganathan, a member of Sri Lanka’s election commission, said disinformation was a major issue there as well in last year’s polls. “We tackled it by meeting all stakeholders, including the media, before the polls. We informed them that violations — such as false propaganda, partial reporting and tarnishing the reputation of a person or institution — would be taken to court. We are proposing a law to the government to control this,” she told this paper.

Both Sri Lanka and Nepal have a large diaspora, and disinformation through the Internet has come from other countries as well.

Nepal’s CEC Dinesh Thapaliya explained: “We had a task force to deal with it. We also have a policy document in place (for social media)…. We find it difficult when political leaders make negative comments or blame other parties and candidates (without basis). But how do you control it?... There has been disinformation originating overseas as well from countries like the US.”

In his speech at the conference, India’s CEC Rajiv Kumar said: “It is not enough to leave it to fact-checkers to detect it. It is like allowing easily detectable fakes to pass through and then leaving it to organisations at the receiving end, like the EMBs, to engage fact-checkers and rescue themselves and the electoral process. Business interest appears to be at work here. It is like first spreading disease and then selling medicines.”

He added: “Social media companies need to introspect before it is too late…. It is in their own interest that fake clutter is detected and blocked before it is too late.”