Exhibits designed by Somsankar Ray in the lobby of Uttam Mancha, the venue of Kolkata People’s Film Festival. The cardboard cut-out in the centre resembles the front of a detergent powder pack. The slogan on it — “For a strong feeling of hatred, use Manuvadi Excel detergent powder”. A shirt whose buttons are open and a pair of khaki shorts are on two sides of the cut-out. “The shirt is not fitting because the chest is too broad,” said Kasturi Basu, a member of a collective that organsised the festival.

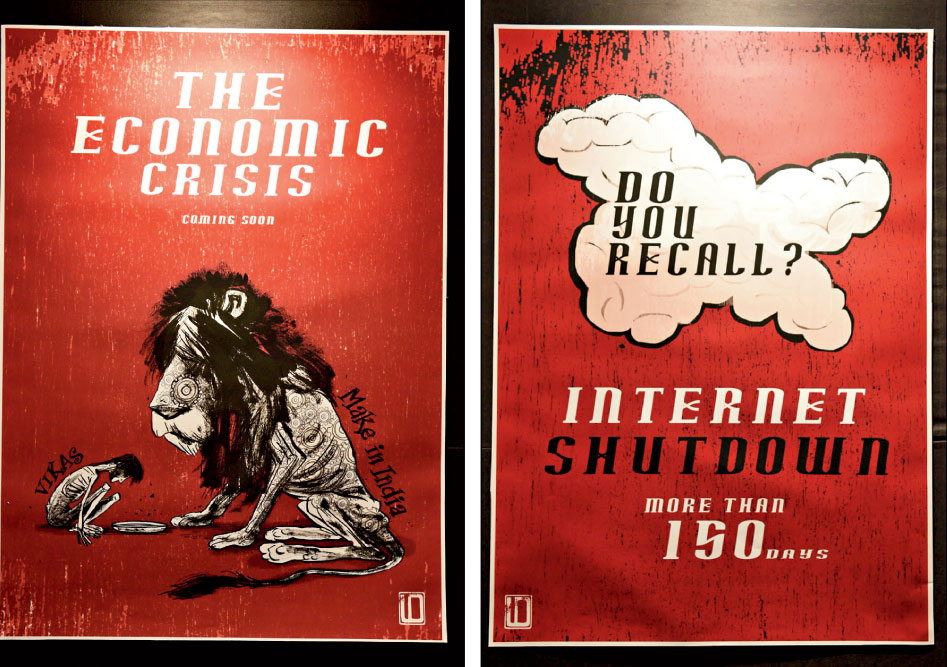

One of the many film posters adorning the wall of the lobby of a south Calcutta auditorium shows a lion and a man sitting together, both emaciated and looking at an empty plate. The lion is called “Make in India” and the man “Vikas”. The title of the poster is “The Economic Crisis; coming soon”.

At another corner of the Uttam Mancha lobby is an acrylic-on-canvas. It shows a crowded boat sailing in water. There is no caption but a peace flag mounted on the boat and the grim faces of the occupants draw a refugee parallel.

The auditorium is the venue of the seventh edition of Kolkata People’s Film Festival, which opened on Thursday and will close on Sunday. “No to NRC, CAA and NPR” is the message of the festival. The lobby has turned into an exhibition of protest against the new citizenship regime.

Spread over the 1,200sq ft area are different artworks based on refugees, migration and lockdown, some of them pulling no punches in targeting the central government.

The films — 34 will be screened — were selected “keeping in mind that we are living in a time when home-grown fascism is on the rise in the country”, said Kasturi Basu of People’s Film Collective, an independent, people-funded, cultural-political group that is organising the festival.

Author Arundhati Roy gave the keynote address for the festival on Thursday. “The real purpose of the all-India NRC, coupled with the CAA, is to threaten and destabilise the entire population…. But undeniably, the main target is the Indian Muslim community, particularly the poorest among them,” Roy had said.

Basu, a documentary filmmaker, told The Telegraph on Friday: “The sudden tussle over citizenship has instilled in people a real, palpable fear of becoming a refugee in their homeland. The art reflects that fear and the pain associated with migration and displacement.”

From posters to sunboard installations, the exhibition has works of seven city-based artists and art students. One of the exhibits is a series of writings and drawings around Calcutta under an imagined curfew and Internet shutdown. The project started on the 20th day of the Kashmir lockdown.

“I spent a lot of time that day contemplating what it would be like to be unable to communicate… and to live through a curfew. It was hard to piece together this experience given the suppression of voices from the valley. I made a series that tried, and may even have failed, to imagine the experience at a human and personal level,” Sumona Chakravarty, who made the series, writes in a note.

Next to Chakravarty’s project is a cardboard cut-out resembling the front of a detergent powder pack. The slogan on it — “For a strong feeling of hatred, use Manuvadi Excel detergent powder”. A shirt whose buttons are open and a pair of khaki shorts are on two sides of the cut-out.

“The shirt is not fitting because the chest is too big,” said Basu, of the Collective.

Anurag Paul, one of the artists, has made sunboard installations based on the works of Ramkinkar Baij, Zainul Abedin and Chittaprosad Bhattacharya. One of the installations shows a crow feeding on a body, based on Abedin’s famine sketches.

“We did not give specific briefs to the artists. They were told about the general theme.... There is deep disturbance among people about the citizenship drive. Artists are compelled to respond to that disturbance,” said Trina Nileena Banerjee, coordinator of the exhibition and an assistant professor at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences.

An acrylic painting. Made by Sampurna Pal, the canvas shows a crowded boat in water. There is no caption but the peace flag and the grim faces draw a refugee parallel. “The subject is derived from real-life footage of Rohingyas, Syrian and other refugees,” said Pal.

A sunboard installation by Anurag Paul shows a crow feeding on a body. It is based on the famine sketches of Zainul Abedin, a Bengali painter known for his depiction of the 1943 famine.

Some other installations made by Paul. The one in front shows Hindu and Muslim men, women and children with two flags, one with “peace” written in Hindi on it and the other in Urdu. The installation is based on a work of Chittaprosad Bhattacharya. Bhattacharya, who died in penury in 1978, was a member of the undivided Communist party and worked as an artist for the party’s publications.

Posters at the exhibition. The poster on the left takes a dig at the make-in-India campaign and vikas (development). The one on the right is a reminder of the Kashmir lockdown. Pictures by Gautam Bose