He begged him to come and watch his play 'Ghasiram Kotwal'.

Little did Mohan Agashe know that Satayjit Ray would one day ask him to play Ghasiram in Sadgati, the 50-minute telefilm Ray made in 1981 for Doordarshan.

Based on Munshi Premchand’s story, Ray’s Sadgati was a searing indictment of the caste system perpetrated by upper class Hindus.

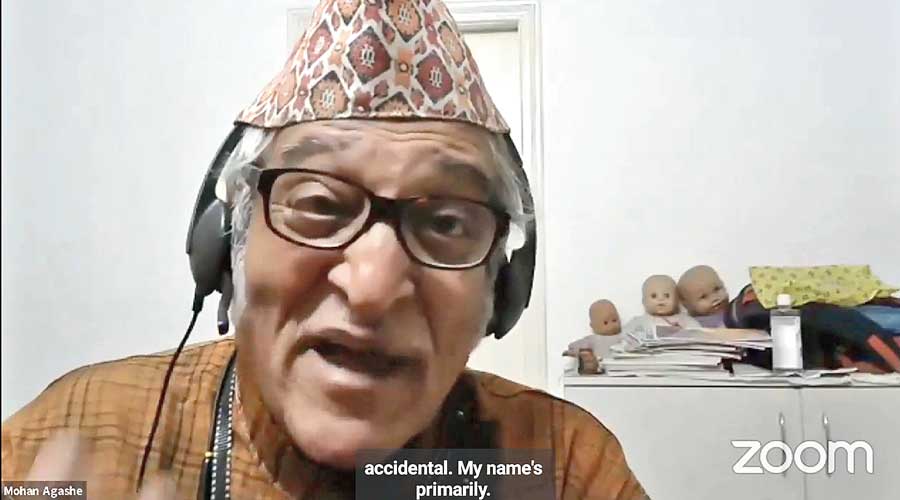

Agashe paid his tribute to Ray on his birth centenary on Friday with an online talk — Elephant and the Blind Man presented by the Victoria Memorial Hall in its centenary year.

Explaining the title of the talk, Agashe, a theatre and film artist, who did just this single telefilm with Ray, said: “I am fully aware that there are a lot of Bengali actors and technicians who have worked with Manikda in umpteen films. My experience with the legendary filmmaker is much shorter. So, what I shall say is my personal experience and not personal information gathered from others. Hence, my story is like the Elephant and the Blind Man.”

Agashe came back from his tour with Ghasiram Kotwal from the US in 1981 and was laid down by a spine problem. He received a type-written letter from Ray offering him the role in Sadgati. He lost no time in accepting it, going at lengths to convince Ray that he had fully recovered.

Satayjit Ray. File photo

Agashe showed Ray’s letters on screen. He goes on to show the next letter, which was handwritten. “This shows how the relationship changed from formal to informal. These days when I agree to do a film, I get a 20-page contract. Its like a slavery contract while I got a humanistic letter from Manikda,” said Agashe. Om Puri (who plays Bhiku in Sadgati) and Agashe boarded a train from Mumbai to Raipur to shoot for the telefilm for a couple of weeks. They were to share a room too. “As Om and I were discussing how would we know who from Manikda’s team would come to meet us at the station, we saw Manikda himself standing on the platform,” said Agashe.

Back at the hotel, Puri and Agashe had to sit with Ray for the sketches, costumes and trials before they were allowed to rest and next day right at seven in the morning they had to leave for shooting.

“On the first day we were late by 10 minutes. Manikda did not say a thing, he just looked at his watch. We were acutely embarrassed. Next day, Om and I got ready quickly and were waiting for him from before seven. Manikda looked at us and exclaimed ‘Am I late?’ Such was the humility of the world renowned filmmaker,” said Agashe.

There was never any need to ask questions to Manikda, for all the answers were there in his kheror khata. “Everyone could access the khata and Manikda had also written the storyboard. No director at that time ever wrote storyboards. He would design his shots, angles and shot divisions depending on what his actors could do for him. He would notice the strong points of his actors and design the shots accordingly. Not once did he raise his voice. Smita (Patil) was obviously his favourite and they had a good rapport,” said Agashe, who felt Ray added value to Tagore and Premchand’s works in the form of giving their works an “audio-visual literacy”.

Describing how Ray would use nature as an additional character, Agashe said: “The climax was supposed to have been shot in scorching sun. But it had begun to rain. So he improvised and there you have that fantastic scene of the dead body in torrential rain, Smita crying and the Brahmin dragging it.”

A lot of filmmakers have done films on caste, but here in Ray’s Sadgati, it is the culture that is the villain, not the humans, points Agashe.

Dukhi has come to Ghasiram asking for an auspicious day for his daughter’s marriage. In a barter, Ghasiram asks him to split the wood in return for finding the auspicious day. “It’s a favour accepted by Dukhi, both the exploiter and the exploited have accepted the culture,” says Agashe. Later, Ghasiram’s wife feels guilty, she asks if Dukhi has eaten, to which Ghasiram asks her to give him food but she refuses saying she can’t start cooking in the heat. Later, when Dukhi dies at the Brahmin’s house, the husband and wife blame each other. “Casual comments become serious in crisis,” said Agashe.

In the scene where Ghasiram goes to the chamar village to ask them to remove the body, nobody responds. While returning Ghasiram encounters the Brahmins who ask him to get the body removed for they cannot go past it to get water. “Here Manikda uses locals. In case the locals couldn’t act he had planned out a scene where he would show Ghasiram’s open umbrella and then a few other umbrellas converging on Ghasiram’s umbrella with the dialogues played out in the background and then the umbrellas would disperse. But fortunately, the locals did manage to act and the scene was shot with the local artistes pitching in,” said Agashe, showing a clip of the scene.

The actor also explained how Ray would use body language to emote scenes. Ghasiram entered his own house after coming back from the chamar’s village. He emerged from the dark and saw his wife who was picking clothes from the clothesline. He exited on the left of the frame to avoid her. She followed him. He laid down on the charpoy. “Ray asked me to put my arm over my face to avoid my screen wife and her questions. When she still persisted, Ray asked me to turn my back to the wife and face the wall. This is how he shows Ghasiram’s reluctance to answer questions, frustration at the situation.”

Comparing Pather Panchali with Slumdog Millionaire, the theatre personality said: “Ray showed dignity in poverty, in image, sound and dialogue. Often one would not notice the background music that he scored so carefully. It would merge with the visuals so much but only later would you realise and go back to it.”

Ravi Gupta of NFDC (National Film Development Corporation), who was a friend of Agashe, told him that Ray had returned unspent amount that was sanctioned for his film to the NFDC. “In his span of career, Ravi had never seen anyone returning a sanctioned amount,” said Agashe.

In Sadgati, too, Ray wrapped up his shooting a day in advance and returned one day’s expenses to Doordarshan.