Down the centuries, Calcutta has gradually moulded itself into a beacon of cosmopolitanism because it has been open to influences from around the world.

From biryani to Borodin (Christmas), the best of Calcutta has been imbibed and then customised in a way that they became inseparable from the city. That melting-pot culture is now facing a threat like never before against the backdrop of the state elections that the Right-wing ecosystem is desperate to trump, Calcuttans from different spheres told The Telegraph.

At stake, they said, was the soul of a culture that has always dared to be different in embracing various ways of life as its own.

Some snapshots of what makes Calcutta different:

King’s Palette

Meat sellers across the city would vouch for Navami of Durga Puja as the busiest day every year. Navami is the final day of Navratri, a period when non-vegetarian food is forbidden in swathes of India.

The mai n elements of the ubiquitous Sunday mutton curry — potato, onion, garlic and chilli — trace their origins to the outside world. Potato and chilli came to Calcutta from America via Europe and onion and garlic were Muslim ingredients.

Some of Calcutta’s iconic structures like The Oberoi Grand, Stephen House, Park Mansions and Queen’s Mansions were built by a clan of mostly wealthy Armenian merchants who preceded the East India Company.

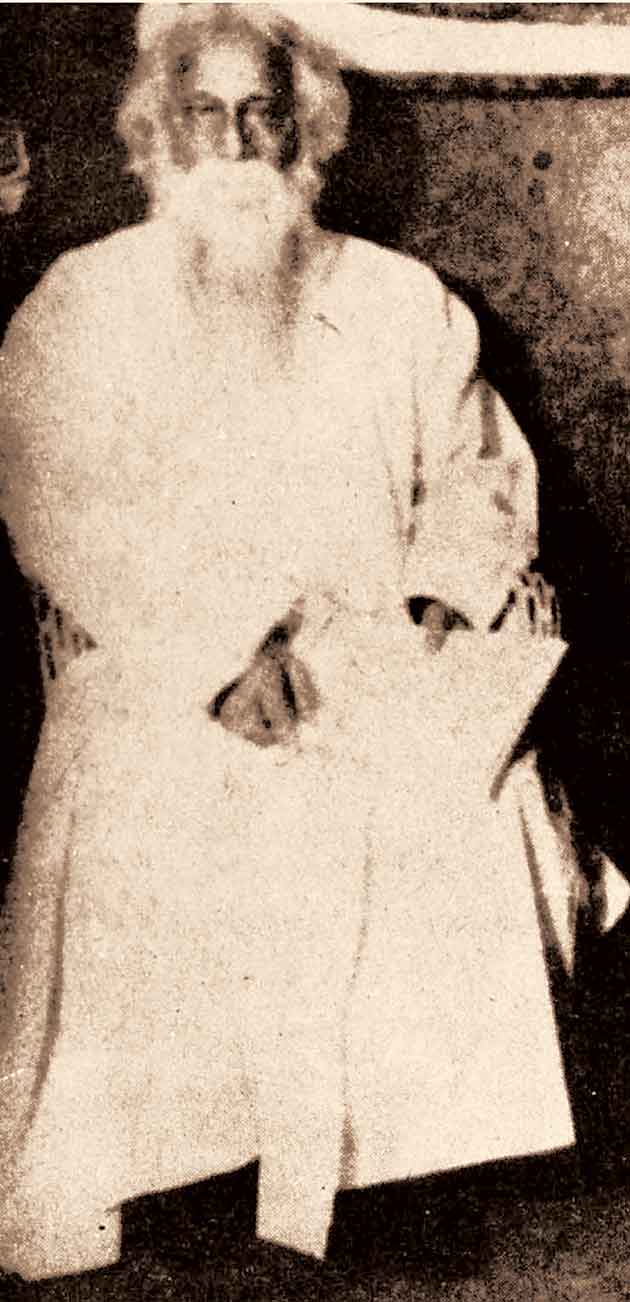

There is similarity in the attire of three foremost icons of Bengal, Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Rabindranath Tagore and Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay — a distinct Persian influence.

Biryani from Awadh, Chelo kebab from Persia and Fish Mueniere from France — Calcutta’s palate is one of the biggest examples of Calcutta’s cosmopolitanism.

Foodlore has it that biryani came to Calcutta with Wajid Ali Shah, the last nawab of Awadh, who arrived in the city in 1856.

Today, a celebration or a festival in Calcutta is synonymous with biryani.

Persian garb

“On any given day, the number of Hindus eating biryani is much, much more than Muslims. Similarly, many Calcuttans look forward to Ramzan because of haleem (a thick and nutritious stew of meat and different lentils), which traces its roots to the Arabic Harees,” said Shahanshah Mirza, the great-great-grandson of Wajid Ali Shah, born and brought up in the city.

Nitin Kothari, the owner of iconic Park Street restaurants Mocambo and Peter Cat, was on a two-day stopover at Tehran on his way to India from Germany many years ago when he had his first Chelo kebab. He introduced the dish at Peter Cat, with a dollop of butter and a fried egg, instead of the raw egg yolk served in Tehran.

The dish became a runaway hit and has remained a top draw in the city’s culinary list, a reflection of how Calcutta imbibes something from another world and then makes it her own.

Fly high, Persia

“I have lived in other places too but the way Calcutta has imbibed, and then owned, aspects of other cultures is unique. This cosmopolitanism would not have worked had it been unidimensional, related to only food, for example. The same cosmopolitanism is visible in all spheres of life in Calcutta, be it architecture or music,” said Kothari, 74.

A snippet about Nahoum’s bakery in New Market that had gone viral on social media a couple of years ago had summed up the city’s culinary character. Its central message — a Jewish bakery with Muslim chefs sees a long queue of mostly Hindus in a Christian festival (Christmas).

The willingness to experiment and embrace the unknown has been an inherent part of Bengali culture, with Calcutta as its epicentre, said scholars and historians. The city’s status as a thriving trade hub also attracted many communities like the Armenians, Parsis and the Chinese.

Jawhar Sircar, who retired in 2016 after having spent over four decades in the Indian Administrative Service, said “unorthodoxy and non-conformity” were the two fundamental characters of the “composite Bengali culture since its formative years in the fourteenth century”.

“In keeping with that tradition, the Bengali culture led by Calcutta was the first to embrace western and Persian influences. The Persian influence is visible in the iconographic dressing style of Ram Mohan Roy, Rabindranath Tagore and Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay,” he said.

Kite flying and pigeon petting in Calcutta also trace their roots to Persian influence. Wajid Ali Shah, who was deeply inspired by Persian culture, is said to have introduced kite flying to Calcutta. The sport has since evolved into being synonymous with Vishwakarma (the god of architecture) Puja in Calcutta, another example of how the city has made a borrowed sport its own.

This readiness to adapt to foreign influences was also at the root of Calcutta’s emergence as the cradle of rational thinking in India, something that had prompted luminaries like C.V. Raman and D.R. Bhadarkar to shift base to the city for academic pursuits, said historians.

Abanindranath Tagore, considered the father of the Bengal School of Art, is another case in point. One of his most famous paintings, The Passing of Shah Jahan, shows the fifth Mughal emperor on his deathbed, staring at the Taj Mahal.

From Iran’s platter

“His art is a tribute to the rich Indo-Islamic past of our country,” said Jayanta Sengupta, secretary and curator of the Victoria Memorial in Calcutta.

“His Arabian Night Series is a rich tapestry of medieval Arabia and colonial Calcutta. Interspersed with characters from the Arabian fairy tales are characters from Jorasanko and Chitpore, around Nakhoda mosque — people Abanindranath grew up around,” he said.

Anthony Khatchaturian, writer and amateur historian of Armenian origin, said the Armenians today numbered less than a hundred in the city but they once played a key role in shaping the history of Bengal and Calcutta.

“We are a dwindling community now because of our internal politics but Calcutta has always given us love. Armenians have always lived peacefully with other communities like Parsis, Jews and Chinese in Calcutta,” said the Calcutta-born Khatchaturian who went to London for higher studies and worked in the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police Service, better known as Scotland Yard, for a decade.

Mixed plate

The Armenian College in Calcutta will turn 200 this year. The Central Bank of Armenia is to issue a special coin to celebrate the occasion, he said.

Calcutta’s politics is but a reflection of her social psychology, said historians and social scientists. At the root of that politics is the right to dissent, to not conform to a majoritarian view. The emergence of a Right-wing ecosystem poses an unprecedented threat to that political character, they pointed out.

“The battle is between openness and orthodoxy, between an inherent heterogeneity and an inevitable homogeneity. It is non-conformity versus an imposed conformity,” said Sircar.

“Till the emergence of the Right-wing ecosystem, no mainstream political party in Bengal openly indulged in communal politics. The Muslim League and the Hindu Mahasabha did but they were fringe players,” he added.

Khatchaturian said “Muslims and Christians would be the first in the line of fire” if Bengal came under a Right-wing regime. “But I doubt if the BJP’s interpretation of orthodox Hinduism would sit well with the Bengali version of liberal Hinduism,” he said.

Armenian grandeur

Historian Sugata Bose, grand-nephew of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, said not differentiating between religions was the biggest tenet of Calcutta’s cosmopolitan character.

“As a kid growing up in this city, Id meant a visit to the house of one of my closest friends. I used to savour the delicacies made by his grandmother. I had always known this was normal, that we never saw ourselves as Hindus or Muslims. I never thought I would have to highlight this to make a point,” said Bose.

“A bigotry in a section of the educated Hindu middle class contributed to the Partition but we managed to recover our cosmopolitan character reasonably quickly. The huge number of Hindu refugees who entered India during the Partition were extremely vulnerable. But they did not veer towards the Right wing led by the Hindu Mahasabha,” Bose said.

The “spectre of 1946-47”, Bose felt, was looming once again on Calcutta. “We have to bring out our cosmopolitan best to resist that,” he said.