The revival of business, albeit marginal, has been a life-changer for many in the city. Salaries credited on time, after a long time, have come like a lease of life for some.

The Telegraph went back to some of the people first met during the course of the lockdown, people who had shared their plight back then, to find out how they were doing in 2021. Not everyone had something to cheer.

Biswajit Barua, bartender

August 2020: The Theatre Road pub where Barua worked was shut. An out-of-work and unpaid Barua was desperately looking for a job, including that of a guard.

January 2021: Barua is a month-old employee at a Sector V lounge, back to doing what he loves most. When this reporter called him on Thursday, Barua was at Esplanade with his family. “I have taken a day off. This is my first outing with my wife and daughter in close to one year,” said the 40-year-old Barrackpore resident.

He got his December salary on time. The lounge is busy on weekends, though the work-from-home culture has affected footfall, he said. But a timely salary is a bonus for Barua, who said he had not got any payment from June to September. Post-Durga Puja, he had apparently received “partial salary” for a couple of months from his former workplace. Now that his income has been streamlined, the topmost thing on Barua’s list is to start clearing his daughter’s pending school fees.

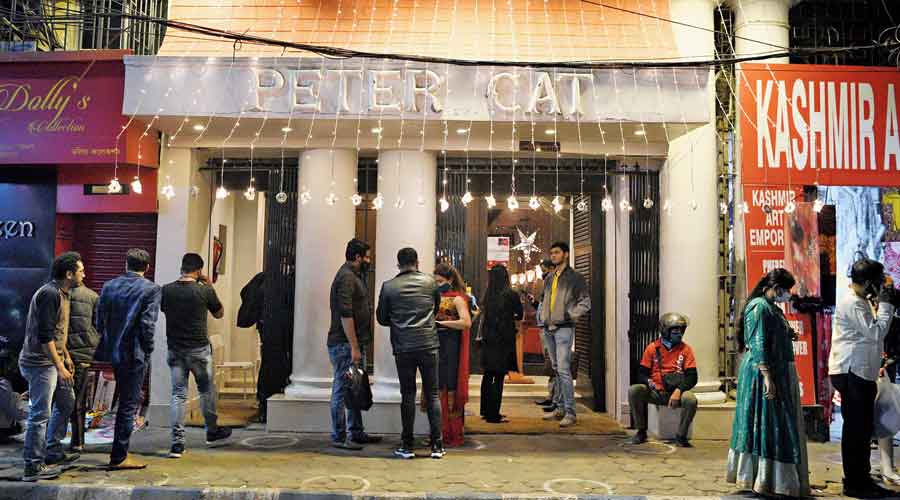

Customers at stalls outside Vardaan Market on Camac Street

Jitendra Pandit, phuchka seller

September, 2020: “Swatting flies and listening to the radio, that is what I am doing,” Pandit had replied when ask-ed about business in the first week of September.

He had reopened his stall behind Vivekananda Park on August 15.

January, 2021: The waiting time for a new customer on Saturday evening was 10 minutes, half of pre-Covid times but still a long way from the months immediately after the lockdown. For the past couple of months, Pandit has been selling around 300-400 phuchkas on weekdays and above 600 on weekends. This time last year, Pandit had been selling over 1,000 phuchkas on weekends.

He had zero income from March 22 to August 15, when his stall reopened. “I had to spend most of my savings on my daughters’ wedding. As a result, I had to borrow money during the lockdown to meet the expenses. Now that some cash flow is back, repaying the money is the first thing on my mind,” said Pandit.

An apparel store on Shakespeare Sarani

Kunal Kapasi, manager of a menswear store

June 2020: Only one item had some takers in Kapasi’s Shakespeare Sarani store — masks.

January 2021: Things have improved reasonably, said Kapasi. He has been selling around “15 to 20” blazers per week. Sale of 40 blazers per week was normal in December and January. “The wedding season was good but the dip in business travels and meetings have taken a toll on the revenue,” said Kapasi.

But he is not complaining. He has people to talk to in the store. From June to August, he would yearn for visitors, even casual walk-ins who would not buy stuff. The employees of the store who had been asked to stay home are back now.

Sonali Chakraborty, co-founder of a social welfare organisation for artisans in Indi

August 2020: A Ballygunge store run by Chakraborty, popular for its indigenous products, had re-opened in July. But there was hardly any footfall even in August. Exhibitions, the support system for the sale of indigenous products, had stopped totally.

January 2021: Thousands of rural artisans she works with are yet to cope with the losses borne during the lockdown, she said. She recently interacted with some Dokra artists in Burdwan and Bankura. “They are left with so much of unsold stocks and the cash flow has stopped. They do not have cash to buy raw material for making new products,” she said.

The only upside she has spotted is how a section of the artisans has for the first time shifted to the online mode to reach out to potential customers directly.

The entrance to Menoka cinema on Southern Avenue

Deepak Shaw, usher at a cinema hall

July 2020: Shaw was then getting half his salary and had to depend on help from several NGOs to run his family.

January 2021: His situation has worsened, Shaw said. The hall is still shut. He has been getting a third of his usual salary for the past few months. Shaw’s employer is said to have called him and a few of his colleagues — employees who have spent two decades or more at the hall — to offer a “severance package”.

“I was offered around Rs 2 lakh in total. After having worked for 24 years, this is nothing,” said Shaw. At the age of 50, it is nearly impossible for him to switch careers, said the Titagarh resident. As the country limps back to normal, the aid from NGOs has dwindled. Shaw’s borrowings — from neighbours to the local grocery store owner — are on the rise.

Divya Agarwal, event manager

September 2020: Agarwal had zero events from March to September. Many of the people she worked with — models to singers — had left their rented apartments in Calcutta to go back to their hometown.

January 2021: The wedding season has been busy for Agarwal, with bookings on almost every day. “But the budget is less than half of what it used to be, because of the curtailed guest list,” she said. Corporate events are yet to take off, though.

“There have been some virtual product launches but they are miniscule in terms of revenue,” she said.

The only sign of hope — the revival of events has allowed Agarwal to provide some financial support to some of her small vendors — decorators, florists and caterers.