A canal has been stolen from Calcutta.

No one knows who the real offender is, but the 4km-long canal that used to drain water from Metiabruz, Garden Reach and Maheshtala has been filled and shops and hawkers occupy most of the stretch.

In government records, this is still a canal and it runs along Santoshpur Road, near Maheshtala.

The lost canal did not have any name. It used to drain water into another canal called Monikhal, which finally merges with the Hooghly.

Defunct pumps and pipes fitted to them still occupy a stretch of the dead canal. The pumps were installed to drain out water from localities served by the canal. They act as reminders that a canal once existed there.

Gautam Roy, a resident of the area, said he had seen water flow through the canal even about a decade back. “When I was a kid, there was a very good flow of water in the canal. There was water even 10 or 12 years back.

But now the canal is dead,” said Roy.

The resident of Santoshpur, near Maheshtala, said most homes in the area get flooded even after a brief spell of rain. “Had the canal not been filled, the problem of waterlogging would not have been so severe,” he said.

Monikhal canal. Sanat Kr Sinha

The canal has been filled over several years. It used to run close to the Garden Reach water treatment plant and the slush removed from the raw water in the plant was used to fill up the waterway.

“This (restoration of the canal) will need big planning. The canal has to be dredged. We will request those who have set up shops there to let us lay an underground drainage line,” said Firhad Hakim, the chairperson of the Calcutta Municipal Corporation’s board of administrators.

Tarak Singh, a member of the board, said residents along both sides of the canal, too, played a part in killing the waterway.

“When the Garden Reach water works was built in the 1990s, there was no plan to manage the slush. The water from the Hooghly is treated and the slush is removed. The slush used to be drained into the canal and it led to the fill-up,” he said.

“The capacity of the canal dwindled with slush being dumped into it. The canal was not even dredged. Over time, residents dumped soil into the waterway and completely filled it. Now they have set up shops on the stretch.”

Singh said a water treatment plant must have a management plan for the slush. Even now there is no robust slush management plan for the Garden Reach water works.

The shops along the stretch are not legal but the civic body will not dismantle them without finding an alternative site for the owners, Singh said.

“We are thinking about a system where we can dredge the canal and bring it back to life again. The canal will run underneath while the shops can function above,” he said.

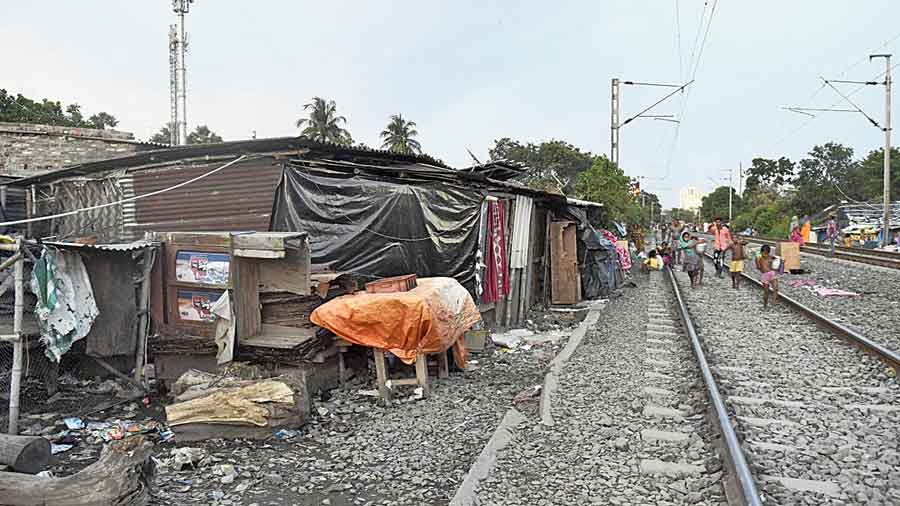

The mushrooming of shops and huts on the canal in Santoshpur is not unique. Across Calcutta, setting up of shops and huts by filling up portions of canals is common. Such encroachments is one of the reasons why it takes longer than usual for water to recede from streets after a downpour.

Sarojit Sarkar, another resident of Santoshpur, said waterlogging was very rare in the area when the canal was alive.

“Monikhal, into which the Santoshpur canal used to drain water, has not been dredged for years. The slush and silt accumulating there has severely impacted the flow of water through Monikhal,” he said.

Sarkar blamed the government, too, for the death of the canal. “They constructed an underground drainage line on a stretch of the canal. A road was built above it,” he said.