Soumitra Chatterjee did as many as 14 films with Satyajit Ray, among the most celebrated of collaborations in the history of cinema. At 5 feet 11.5 inches, he turned out to be a bit too tall for Ray’s Aparajito, and hence his debut was with Apur Sansar, the third and concluding part of the Apu Trilogy based on two Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay novels. How did Ray end up choosing Soumitra? Was it the screen test? Was it the actor’s diction? And when did he finally tell him that he was to play Apu?

Here’s Soumitra in his own words. Excerpts:

Manik da used to live on Lake Avenue those days. He was sitting in the room with the familiar kurta-pyjama. The moment I entered, he said, 'Oh dear, you've turned out to be much too tall.' Restraining himself immediately, he said, 'Please come in, take a seat.' I was shaken. How engrossed he must have been in his work to be able to say something like this. It only meant that he was looking for Apu everywhere, all the time. He had already received international recognition, and even won several awards. I was touched by the fact that he spoke to a nondescript stranger like me for such a long time and on such a variety of subjects. I had noticed all his life that he spoke to everyone freely and with complete sincerity.

His baritone and his towering figure inevitably projected the image of a unique personality, but he never tried to create a distance between himself and others. Still, no matter how many funny things he said or light subjects he touched upon, playing the fool with him was unthinkable. And yet, when the time was right, he used to laugh and joke with many of us - just as we do with our friends - including me.

I didn't realise it then, but I learnt later that Manik da would size up new actors and actresses for certain specific abilities during the course of his first conversation with them. Qualities such as their manner of speaking, their voice and pronunciation, what their expressions were like, and if they could speak Bangla fluently. I had noticed from the beginning that he put particular emphasis on their ability to speak Bangla – the sort of words they used during their everyday conversation. I have worked with many other film directors afterwards, but none of them usually paid much attention to this aspect. Everyone who's worked with Satyajit Ray knows the importance of dialogue delivery in his films.

He had asked me two specific questions in the course of our tête-à-tête that day – whether I really loved acting, whether I was ready to act in films, if necessary. In other words, he wanted to observe just how keen I was on acting. Given my immense fascination for Pather Panchali and the identity of the person asking the questions, my response was exactly as it ought to have been.

'Exactly how tall are you, Soumitra babu?' Manik da asked suddenly as I was about to leave. 'Five feet eleven and a half,' I said. Summoning his production manager Anil Chowdhury, he said, 'Would you please stand next to him for a minute, Anil Babu?' When I left, he repeated, ‘Do come again, keep in touch.’

After that first meeting, I didn't go back very often although he had asked me to. Why disturb such an important man while he was busy with his work? I did take two or three friends of mine to see him in case he found any of them suitable for Apu. He didn't, though. Eventually, he picked Smaran Ghoshal. There was a stir again after the release of Aparajito – all of us loved it; it was indeed an extraordinary film. We discussed the distinctiveness of many of the scenes over and over again- the ghats of the ganga in Kashi, Harihar's death, Apu plucking grey hair off the old man's head and then racing away as soon as he was paid, Apu screaming 'Africa!' dressed as an African child, Apu missing the train deliberately so that he could go home, Apu's first visit to Calcutta and many other scenes which are still preserved carefully in my memory. I used to recollect these scenes every now and then, and do so even more so now.

Youth lorded over our lives those days, with endless adda at the Coffee House. Another of Manik da's assistants, Subir Hazra, used to join our Coffee House sessions. He would often tell me, 'He hasn't forgotten you, he's going to send for you soon...' and so on. And I would say, 'Forget it, why should he send for me...' Naturally, I assumed these were just empty promises. I joined All India Radio soon afterwards _ the office was in Garstin lace, the year, 1957. I spent some time in bed with chicken-pox that year. When I had recovered, I was home one day, running my hand over the mementos of my illness, when Subir arrived. 'Come with me, Satyajit Ray has sent for you.' I went a few days later. As soon as I entered he exclaimed, 'There you are, please come in. But everything seems fine, I don't see any marks on your face! Someone was saying you have developed pockmarks. This is nothing, it should be fine.' After a pause, he added with a smile, 'I hope you're still as keen on acting as you once were.' Lowering my eyes, I said, 'yes, of course, I am.’

Anyhow, after we had spoken about some other things, Manik da said that he had decided to make another film taking cue from the second part of Aparajito, and that he might need me for it. Although he was always straightforward in whatever he said, he was also very careful; so he added immediately, ‘I am not giving you my word at the moment, but I want you to be prepared.’ A natural reserve prevented me from telling him at once that I had been waiting impatiently for one opportunity to work with a film-director like Satyajit Ray. ‘I’ll take a screen test soon,’ he continued. ‘A very simple affair.’ Then we talked about other things for quite some time, after which he said, ‘Why don’t you come over to the studio when I’m shooting?’

He was shooting two films virtually simultaneously – Parashpathar (The Philosopher’s Stone) and Jalsaghar (The Music Room). Even today, after all these years, I’m astonished when I consider the energy and the genius needed to make two films of that quality at the same time. Parashpathar was the first to be completed, followed by Jalsaghar. He had somehow found out that I was in regular contact with Sisir Kumar Bhaduri. He had even come to know that I visited Sisir Kumar frequently, borrowing books from his collection and getting him books to read. He would ask after Sisir Kumar during our conversations – what kind of books he read, what kind of books he enjoyed reading, what kind of discussions we had about acting – and so on.

When he learnt that I was a student of literature, Manik da would sometimes discuss books with me. Such discussions with a new actor – and that too about literature – were unthinkable in the environment of Bengali cinema. Besides two or three cultured, well-educated film-directors, I have never met another person like him ever again.

On the appointed day I went to the studio to watch Parashpathar being shot. I was dazzled by Bansi Chandragupta’s sets. Was it humanly possible to create such sets? I couldn’t even imagine such a thing at the time. I should mention that we had become instant fans of Satyajit Ray’s cameraman Subrata Mitra and art director Bansi Chandragupta after watching his very first film. We used to discuss them intensely, for both of them were like demigods for us. They’re just the kind of people a great director’s unit should have, we’d say. The sets hadn’t been completed yet, with the finishing touches still being put. I went up close and began to watch, practically open-mouthed. Manik da was preparing for the shoot. He caught sight of me devouring the scene with my eyes. Later I realised that Manik da had arranged all this for my convenience, opening all the windows to the special world of cinema to me so that I could get familiar and comfortable with it.

The famous party scene of Parashpathar was to be shot that day. Virtually every famous actor of Bengali cinema was present for the shoot. Manik da gave me the opportunity to watch how renowned actors perform in front of the camera, how natural their behaviour is. In short, he was preparing me not to get nervous when it was my turn.

Manik da still used the formal ‘apni’ with me at the time and hadn’t yet told me that I was to act as Apu. I had expected to be asked to play a minor character. Or perhaps he had hinted at something that I had not grasped.

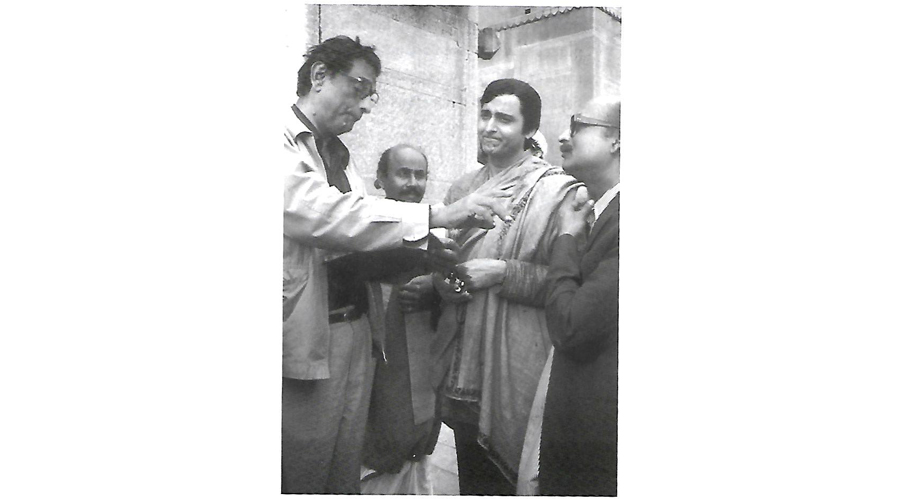

The practical aspects of shooting a film gradually became clear to me during my visits to the studio. I worked at the radio station and went off to watch Manik da shoot whenever I could. One day, I was there to watch a scene from Jalsaghar being shot, with Manik da giving me a vantage point as usual. After the shooting had ended for the day, I had to go off for my radio job. So I went up to him and said, ‘I have to go now Manik babu.’ Even if it was without any awkwardness, the words ‘apni’ and ‘babu’ did exist between us till that time of 1957. But both words vanished forever soon afterwards. The ‘apni’ that I did use with him till recently was just like ‘tumi’ in nature and in terms of intimacy. As I was about to leave, he said, ‘Let me introduce you to Chhabi Biswas, you haven’t met him, have you?’ I shook my head. But why did he suddenly want to introduce me to the legendary actor Chhabi Biswas? I was astonished as I was pleased. Going up to Chhabi Biswas, he said in his customary baritone, ‘Chhabi da! This is Soumitra Chattopadhyay, he is playing Apu in my next film, Apur Sansar.’ The penny had dropped! The chandelier on the sets of Jalsaghar began to sway in front of my eyes; my feet left the ground – I was flying, holding hands with the stars. That was when I realised for the first time that he had always thought of me as Apu. On the bus to the office, I wandered why it wasn’t speeding like a meteor – it was a feeling of pure, irresistible joy.

The days that followed went by in a blur, flying past like the pages of an open book put down by the window. The affectionate relationship that developed between us right then led Manik da to protect me all his life with the love of a father. Visiting him at his Lake Avenue house was no longer a special effort on my part.

He had personally taken several photographs of me in his room – stills which he spread out in front of his wife, whom I addressed as Boudi, and other members of his unit for discussions. He discussed my photographs with me too. He advised me to read Aparajito carefully once more in order to transform myself into Apu, and discussed all the books about acting that I had read. He also told me to read certain books I hadn’t read. I had already read Stanislavsky’s My Life in Art and Building a Character. One day he asked me during a conversation, ‘Have you read Stanislavsky’s An Actor Prepares, Soumitra?’ ‘No, I couldn’t get my hands on it,’ I said. He immediately gave me his copy of the book to read. I never saw Manik da being pedantic in his life, although there was no scope for doubt that he could have given classroom lectures on a number of subjects if he had wanted to. He always said what he needed to succinctly. Handing the book to me, he said, ‘When you read this you will realise how useful it is for beginners.’ He lent me other books of the same kind afterwards. Someone who had read so much, possessed such a superb collection of books, and was so immensely intelligent still exercised extraordinary restraint when speaking, never saying anything more than the essential – this too was a real sign of greatness. Every experienced connoisseur of the arts knows just how many people in India were capable of speaking or writing both Bangla and English the way Satyajit Ray did – my endorsement is unnecessary. He hated displays of erudition and the pretence of punditry.

Excerpted with permission from translator Arunava Sinha

Book: The Master and I, Soumitra on Satyajit

Author: Soumitra Chatterjee (translated by Arunava Sinha)

Publisher: Supernova Publishers

Price: Rs 395