The craft of Soumitra Chatterjee, a screen actor of unmatched timbre, hinged on two distinct poles. At one end was his personality that radiated charm and gravitas, at the other was his magical ability to dissolve into a role so completely as to become one with the fictional character he played. That apart, he straddled the two streams of Bengali cinema – artistic and commercial – with equal ease. No wonder Soumitra Chatterjee had an extraordinarily varied film career.

He was a thinking man’s screen performer who combined deep thought and awe-inspiring creative dexterity with deceptive ease to flesh out many a memorable character that will live on as long as cinema exists. His worldwide reputation — few Indian actors can match it because it isn’t mere movie stardom that we are talking here — is obviously intertwined with that of the trailblazing Satyajit Ray.

If Ray was an imposing banyan, Soumitra was one of its sturdiest branches, which eventually spread out and grew its own roots to itself become a flowering tree that never stopped growing and blooming. In the late 1990s, French filmmaker Catherine Berge made a documentary in tribute to Soumitra and titled the work Gaach (Tree). We have lost the tree; the flowers and fruits it bore will stay with us forever.

In India, outside of Bengal, Soumitra’s name might ring at best a faint bell except in informed circles. This has as much to do with the distance he kept from the pan-Indian Hindi cinema – into which his great contemporary Uttam Kumar forayed with a fair amount of success – as with the kind of films he generally championed.

Soumitra had no peer in India. He worked with Ray until the very end of the latter’s life, from 1959’s epochal Apur Sansar (the actor’s screen debut) to the maestro’s second last film, Shakha Prosakha (1990), building a 14-title body of work that would have ensured him immortality even if he hadn’t done anything else in life. But as things panned out, he did an immense amount of work not only in the movies, but also in theatre, poetry, publishing and art.

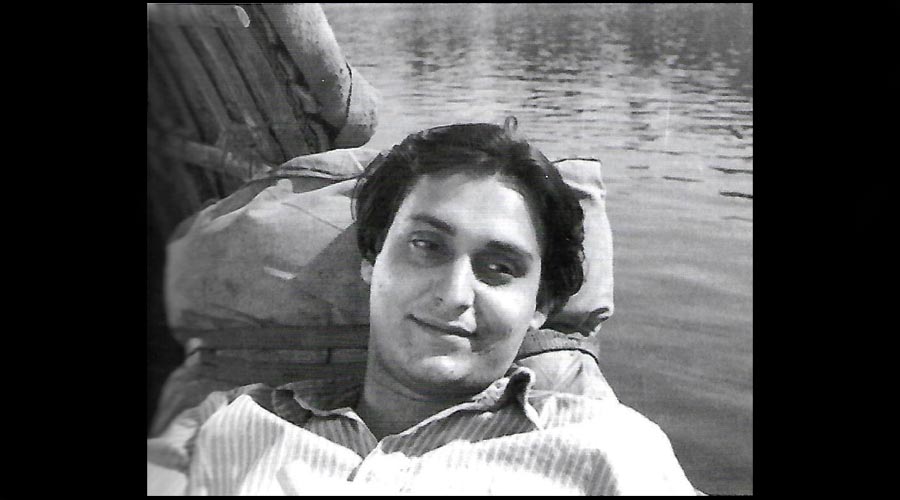

In Apur Sansar. The Master and I

Soumitra was in his early 20s when Ray decided to cast him in Apur Sansar. He was a visitor to the set of Jalsaghar, Ray’s fourth film, when the director introduced the youngster to Chhabi Biswas as “the lead actor of my next film”. Soumitra was taken by surprise. In fact, even after filming of the last part of Ray’s fabled Apu Trilogy began, the actor wasn’t sure he had chosen the right calling.

He spent the first ten years of his life in Krishnnagar. He was a diffident boy. The stage – to begin with, his mother’s bed was the arena around which he used her saris and bedcovers as wings and curtains – was his big refuge. It allowed him to hide behind assumed personas and express himself. For one, Krishnangar, poet, playwright and musician Dwijendra Lal Ray’s hometown, had a flourishing theatre culture. Two, his father, a practising advocate in Calcutta High Court, was an amateur actor. His grandfather, too, had links with the performing arts.

The shift to Calcutta for a post-graduate degree in Bengali literature exposed the young man to the city’s professional theatre, then dominated by Sisir Kumar Bhaduri. Soumitra learnt acting under the tutelage of another doyen of Bengali stage, Ahindra Choudhury. Ray, on his part, was quick to recognise the actor’s potential. He gave Chatterjee the first draft of the Apur Sansar script well ahead of filming.

Ray had already made four films but never had he given any actor the entire script to read and well before the shoot had begun at that. The director also gave the debutant two sheets of paper that spelled out the profile of the film’s titular character down to the minutest detail. Another first! Ray’s faith paid off in a way that quickly became the stuff of legend.

The Ray-Soumitra partnership was, in terms of output and impact, on par with the iconic director-actor combinations that Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune, Ingmar Bergman and Max von Sydow, Federico Fellini and Marcello Mastroianni and Yasuziro Ozu and Chishu Ryu forged.

The films that Ray and Soumitra made together put Bengali and Indian cinema on the world map like nothing else ever has before or since. But Ray was only one chapter of the eventful career of the Dadasaheb Phalke Award-winning actor who was in the business for well over six decades and died literally with his boots on. Only late last year, he had two new films, Barun Babur Bondhu and Sanjhbati, out in the multiplexes.

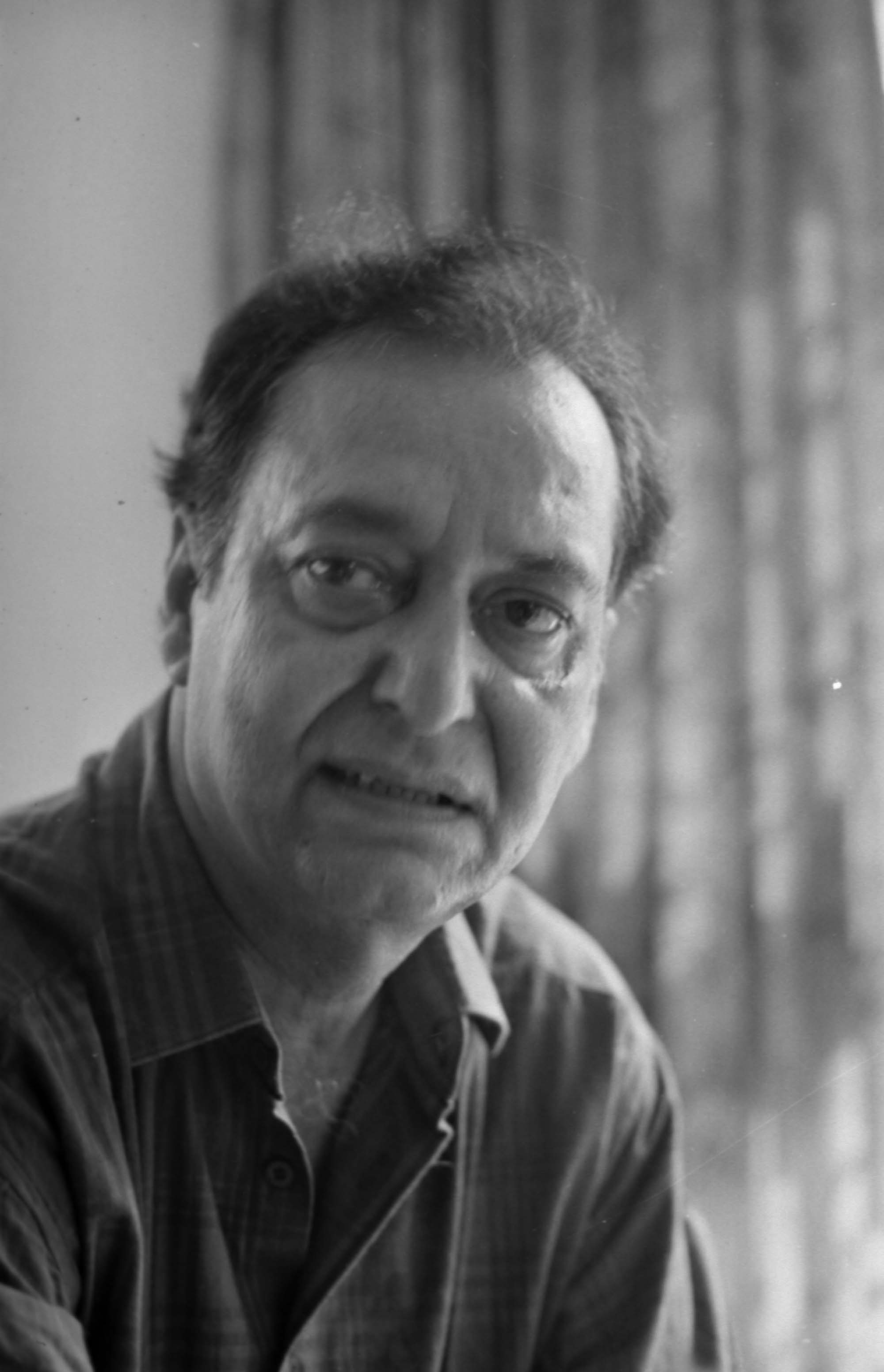

At a function in Calcutta. The Telegraph

It is easy to forgive those that believe that Soumitra’s reputation rests solely on the work he did with Ray. But nothing could be further from the truth. The iconic thespian held his own under many other directors and in several other strains of Bengali cinema. He also collaborated felicitously with Tarun Majumdar (Sansar Simantey, Ganadevata), Ajoy Kar (Saat Paanke Bandha, Parineeta) and Dinen Gupta (Basanta Bilap, Sangini), among many others.

Soumitra’s association with Sharmila Tagore began in Apur Sansar, which was the latter’s debut too. Ray subsequently cast the two enduring Bengali stars together in two films made ten years apart – Devi (1960) and Aranyer Din Ratri (1970). The Soumitra-Sharmila screen pairing, thanks to the sheer collective critical acclaim the three Ray films garnered, remains unparalleled in the history of Indian cinema.

Soumitra forged a hugely successful screen pairing with Aparna Sen, who debuted opposite him in the third segment of Ray’s Teen Kanya (1961) – Samapti. Soumitra and Aparna were also cast as a pair by Mrinal Sen in Akash Kusum (1965), by Dinen Gupta in the 1973 romantic comedy Basanta Bilap, and by Ray’s assistant Nityananda Dutta in Baksha Badal (1965). The last-named film had music by Satyajit Ray.

With Tanuja, who had an active stint in Bengali cinema in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Soumitra featured in three major films – Protham Kadam Phool, Teen Bhubaner Paare (both 1969) and Aparna (1972). Teen Bhubaner Paare, in which he played a drifter who falls in love with a woman way out of his league, had him jiving to the timeless hit “Jibone ki paabona bhulechi shey bhabona”, sung by Manna Dey.

The song led into the interlude “Ke tumi Nandini aage toh dekhini”, which quickly passed into film music folklore. The number ranks alongside Ei poth jodi na shesh hoye, the Uttam Kumar-Suchitra Sen duet from Saptapadi (1961), as the most unforgettable musical set piece ever mounted in a Bengali film.

Rarely, if ever, was Soumitra not on song as an actor. The range of roles he played was nothing if not phenomenal. Two films come instantly to mind – Goutam Ghose’s Dekha (2000), in which a he played an ageing glaucoma-stricken poet who goes nearly blind, Suman Ghosh’s Podokkhep (2006), for which the veteran actor won a long overdue National Award for the best male lead performance of the year, and the more recent Mayurakshi, directed by Atanu Ghosh, who cast the seasoned actor as a dementia-afflicted retired professor of history.

Walking up the podium. The Telegraph

Soumitra’s early triumphs were primarily in films made outside of the Bengali cinema mainstream – besides Ray, he worked with Mrinal Sen (Akash Kusum, 1965) and Tapan Sinha (Kshudita Pashan, 1960). But he eventually established himself as a major commercial movie star, starting with the success of Sinha’s Jhinder Bondi (adapted from Anthony Hope’s The Prisoner of Zenda), in which he shared screen space for the first time with Bengal’s reigning matinee idol Uttam Kumar.

Soumitra’s life did not begin and end with cinema. He remained active in theatre, co-edited a literary journal for 18 years (Ekkhon, 1961-1979, with Nirmalya Acharya), authored a dozen books of poetry and also produced paintings of no mean quality. Do we know any other film actor who can boast such a range of creative pursuits?

Soumitra’s acting technique was a fine blend of minimalism and meticulousness. As a result, his histrionic sleights were often invisible to the naked eye. At their best, they could only be felt. It was the subtlety of his art that made it possible for the incredibly versatile Soumitra to internalise Apu, Amulya (Samapti) and Narsingh (Abhijan), three dissimilar characters he played for Ray in a span of four years, without the effort showing.

For another Ray classic, Charulata, Soumitra changed his Bengali handwriting for good. He spent six months practising the letters and strokes of a pre-Tagore era and emerged, at age 27, with an all-new running hand. Didn’t we mention his ability to merge himself with a screen character? It bordered on the miraculous.

Saibal Chatterjee is a cinephile who has been writing on films for over three decades.