In the 1950s and 60s, cars had expelled cyclists from the streets of Holland, but at great expense. By the early 1970s, road accidents were claiming thousands of lives every year and among the dead were many children. This led to a movement called Stop de Kindermoord, meaning stop child murder.

In the Dutch capital of Amsterdam, activists adopted the bicycle in protest. Around this time, the Arab countries had imposed an embargo on export of oil to Holland and a few other European countries for supporting Israel. This led to a steep rise in oil prices. Even politicians began to see the advantage of a lifestyle not too dependent on oil. Holland, and especially Amsterdam, began to change.

Amsterdam is currently known as the bicycle capital of the world. Calcutta today, despite all obvious differences, may be where Amsterdam was in the 1970s, feels Bicycle Mayor of Calcutta Satanjib Gupta. The title conferred on Gupta by BYCS, an Amsterdam-based global network that promotes the bicycle, may sound absurdly grand, but the lockdown has led to so many absurdities already.

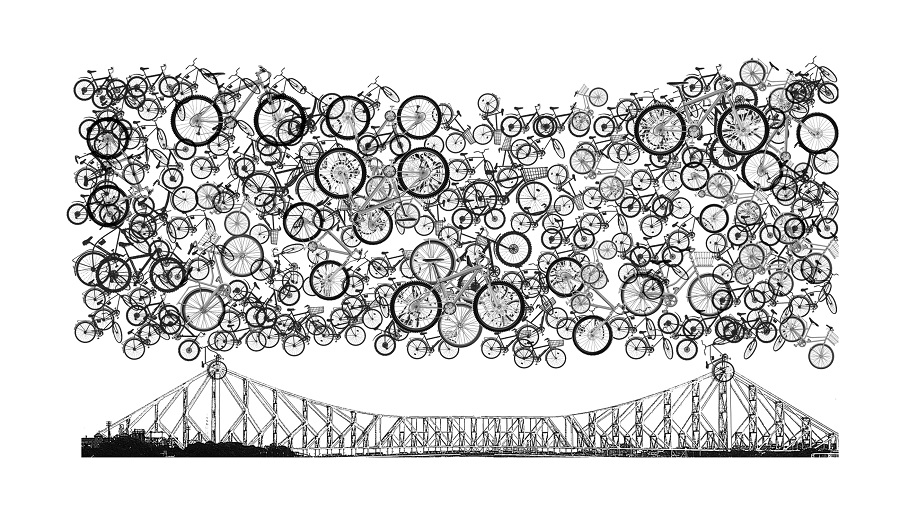

“Have you seen photographs of the Howrah Bridge during lockdown,” asks Gupta. “Full of bicycles, it was a wonderful sight.” The number of bicycles in the city’s streets, estimated to have been over three lakh before the lockdown, has gone up several times. Its sales have soared since June. “The cycle is not only helping maintain livelihoods but also opening up livelihood options,” says Gupta. It is helping the delivery of products and services.

This, for Gupta, could be the moment of change for Calcutta.

The bicycle is the perfect vehicle for social distancing, for exercise, especially for lung power — advocated during the Spanish Flu, too — and for immunity. It is fuel-free and hence an antidote to climate change; cheap and almost zero-maintenance. It ensures equality of all and had played its part in empowering women. And yet, how poorly it has fared in Calcutta, which also has the highest percentage (11 per cent) of bicycle commuters among all Indian metros. Over the last two decades, it has slowly been pushed off the streets by the authorities.

A circular issued by the police commissioner in 2008 had banned bicycles, categorised as “slow-moving vehicles”, from 38 city streets. In 2013, another police circular raised the number of streets to an impossible 174. In 2014, that was brought down to 62 by yet another circular. Cyclists would complain of harassment by the police, who would stop them and impose fines arbitrarily.

So this year, after a nod from the chief minister, on June 9, the latest police circular raised hopes. It stated that with public transport restricted because of the pandemic, all bicycles would be allowed in the lanes and bylanes. But the harassment of cyclists continues, claim enthusiasts, and there is no clarity about routes. “Why can’t the main thoroughfares be opened for now to bicycles,” asks Gupta.

A humiliating fine had led Raghu Jana to found the Kolkata Cycle Samaj with his friends in 2009; its primary aim is to get the ban lifted. Jana, a private tutor, who took part in political movements, speaks about the peculiar position the bicycle occupies, or does not occupy, in the law and regulations of the city.

The classic way to undermine someone is to look through. It applies to bicycles too. “The bicycle is never addressed,” rues Jana. It is only banned. “Two years ago, we saw a police notice asking cyclists to follow the rules. We were glad. They were speaking to us,” he says.

Encouraged, he and his Kolkata Cycle Samaj colleagues met a senior police official. But nothing changed.

Jana points out that the police circulars were issued under the West Bengal Traffic Regulation Act, 1965, and the West Bengal Motor Vehicles Rules, 1989, but there is no specific body of rules in the city relating to the bicycle. “We are only told what we can’t do,” he says.

The roads have only “No Cycling” signs.

Sabuj Sathi, the state government showpiece programme, is far more successful in distributing bicycles among school students in the districts. This is ironic for a city in which the bicycle, which became popular in its contemporary form from the 1880s, had enjoyed pride of place. It is even said that in 1870, a Santragachhi resident manufactured a bicycle that would require two persons to ride it, says Gupta. Eminent Bengalis, including Dwijendranath Tagore, J.C. Bose and his wife Abala Bose, P.C. Ray and Nilratan Sircar, had all patronised the bicycle, Gupta adds.

In Rabindranath Tagore’s short story Ponrokkha (1911), a young man yearns for a bicycle, which promises him freedom and joy, at only Rs 125. Personal Assistant, a 1959 Bengali film, has a beaming Bhanu Bandyopadhyay breezing through the still elegant and roomy central Calcutta roads on his bicycle, at par with motor cars.

“Just the joy of riding a cycle,” says Jana. “Your body develops a unique relationship with it.” He questions the right of the police to decide the fate of cycles in the city. “This is a matter of urban planning,” he stresses. And of policy. Yet he is hopeful. “This is a moment of transition. Many may not want to give up on the joy of riding a bicycle when things normalise,” he says.

The bicycle just needs a little encouragement in the city.“At the moment, it will be enough if the guard rails, lying everywhere now, are used to mark off a part of street at one end for cycles,” says Jana. Official bicycle lanes can be created later. “This is also the best moment for the ban to be lifted,” he adds.

State transport secretary Prabhat Mishra is happy that so many cycles are in the streets. “But finding space in the city (for bicycles) is the biggest challenge,” he adds. In Calcutta, roads constitute only 7 per cent of the city area.

The larger issue is an absolute lack of transport policy, says leading environment activist from the city, Naba Dutta. Since the formulation of the Comprehensive Mobility Plan (2001-2025) and discussions around another plan in 2011, there has been no planning for the city,” says Dutta. Roads, flyovers, overbridges have been built, but in a piecemeal, ad hoc way. “CNG buses are yet to roll out in the streets and bicycle lanes were part of the original plan of the E.M. Bypass.”

The lack of planning has been made worse by the lack of environmental concern, says Dutta. Like bicycles, trams have been removed from the city streets. The car culture has overtaken everything and the bicycle has become the poor person’s vehicle. All this despite the fact that vehicular emissions are the biggest contributor to air pollution in Calcutta.

At more than 350 cars per kilometre, Calcutta is one of the country’s most car-dense cities. Since the lockdown, with many cars off the street, the air feels much clearer. A study by the Centre for Science and Environment shows that peak levels of particulate matter or PM 2.5 and nitrogen dioxide have dropped by 46 and 74 per cent, respectively, during the lockdown compared with pre-lockdown days.

“The stretch from Sealdah to Dalhousie can be made car-free. Before the lockdown, lakhs of people walked down the stretch every day to reach their workplaces and back. Same for the Chitpore to Esplanade stretch,” says Dutta. Calcutta could also use its waterways, he adds. “From our environmental platform Sabuj Mancha, we have been repeatedly asking the government for a comprehensive transport policy,” says Dutta, a cyclist himself.

Urban planner Tathagata Chatterjee, who is professor in the department of Urban Planning and Governance at Bhubaneswar’s Xavier University, also insists on an overall transportation policy, but with planned intervention. “Just setting up bicycle lanes is not enough. This happened in Bhubaneswar, where now they are mostly used as parking.”

“Planning for cycle and pedestrian infrastructure needs to be addressed together,” says Chatterjee, stressing on a strategy that uses different modes of transport. He assesses the disadvantages of Calcutta to accommodate such transport: the population density, extreme low road space, mixed traffic, road condition, encroachments, car parking, garbage dumps, movement of pedestrians, chances of collision with motorised vehicles, particularly autos, scooters and motorbikes, weather conditions of rain and heat, and lack of supporting infrastructure. Where does one park the bicycle is an important question he raises.

But Calcutta has its advantages. It is a city of small distances. An average trip length in Calcutta is about five to six kilometres. Chatterjee says that this and a system of feeder transport can help the bicycle here. “In Calcutta, cycles should be used for short neighbourhood streets, not main roads. Dedicated cycle lanes are more suitable for planned areas such as New Town and Salt Lake,” he adds. According to him, while treating trams as feeder transport, authorities need to focus on creating a non-motorised rail-based mass transit system linking suburban rail, Metro rail and trams. Attention should be paid to good pedestrian infrastructure too. Thought has to go into creating parking spaces for bicycles. Cycle-friendly cities such as Copenhagen, London, Singapore — have done all of this. “The Comprehensive Mobility Plan has to be revisited,” says Chatterjee.

In the meantime, here, the public sector undertaking Hidco is encouraging bicycles in the New Town area and the Kolkata Metropolitan Development Authority has decided to take part in the national-level competition “Cycles 4 Change Challenge” organised by the Union ministry of housing and urban affairs.

A 56-year-old Calcuttan, Sudipto Roy, chief public relations officer of a multinational company that also manufactures car batteries, has turned cycle fan. He has taken to cycling to work every day during lockdown. He says, “In two months my blood pressure and blood sugar levels have come down.”

He too has a question — “Why does this city reward the motorists and punish the cyclists?”