The first time Samir Chatterjee played table tennis was at a friend’s place, just after the Matriculation examination. “It was March, 1939,” says Chatterjee. They had placed a net on a dining table, though they had proper racquets. Chatterjee’s life changed that day.

“It was as if I found a part of me that was lost,” says Chatterjee, who turned 99 in July.

He went on to become a table tennis star in Bengal, feared for his forehand topspin and smash. A state champion, he met world champions, though could not represent India officially ever, to his regret.

Later in life, he would be considered a “living encyclopedia” on table tennis, a master of every aspect of the game, as a player, coach, umpire and mentor of younger players.

He was also a prolific writer on table tennis who contributed articles to several newspapers and journals in Bengal and outside.

His friend Kumar Ghosh, at whose dining table it all began, would become another top player.

Nothing came easy to Chatterjee. But nothing diminished his passion.

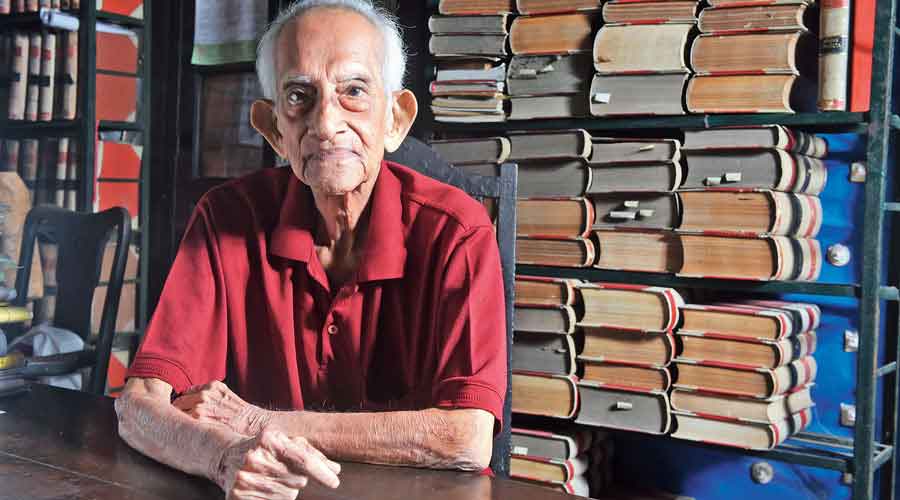

A resident of Bhowanipore, he is waiting for me at the Ballygunge residence of a family friend. He is a small, frail, gentle man and he cannot see very well. But his eyes light up as he begins to talk. His memory remains surprisingly sharp.

He remembers the year and month and sometimes the exact date of an event — and these are delivered with a stunning precision, memory marking a triumph against time. He has seen many ups and downs, and material rewards have eluded him, but he looks at his long life as a wonderful, rich, exciting journey. He dwells on every detail.

Growing up in a large family in Bhowanipore, he loved every sport, including football and cricket.

“But I was a thin child and a bhalomanush (simple) and was teased for being both,” smiles Chatterjee, who was a student of South Suburban school and Mitra Institution, where stalwarts like the poet Kalidas Roy and the mathematician K.C. Nag taught him.

So he stayed away from the rough sports. Then table tennis struck. Like fate.

“I passed Matric in the first division and took admission in the science stream in Asutosh College,” but he was obsessing about table tennis.

“I could not sleep or eat. The books looked frightening, too big, and the War had started,” recalls Chatterjee. “Prices were going up.”

His family had limited resources. “And I was making progress neither in studies nor in table tennis. I could not take the Intermediate examination,” he says. He felt guilty. Being the eldest of nine siblings, also responsible for his family.

“On August 19, 1941, at 19, I took up a job as a clerk at the war office, in the department of the chief controller of purchases department (munitions), at Dharamatalla, for Rs 45 a month,” he says. A year or so later, Japanese war planes began to mark the Calcutta sky and the bombings began. “I remember the shattered glass at a bombed building in Dalhousie,” says Chatterjee.

All the while he had been practising table tennis, mainly at the Bhowanipore YMCA, which later became Khalsa School. He began to travel to other Indian cities to participate in major tournaments.

An encounter at a Hyderabad tournament in 1943 made him find his game. It had basically been “chop-defence” and an occasional backhand smash. He could never master the forehand. At the tournament he saw a player from Bombay (Indian cities were still known by their colonial names), 40ish, who wore adjusting heels because one of her legs was shorter. Her forehand smashes were electrifying. “I got a 440 volt shock,” says Chatterjee. “If she can, why can’t I? I asked,”.

He mastered the forehand, his biggest weapon, the very same day, after missing it for years.

He did not ever need any distraction, not even romance. “No woman ever came as close to me as table tennis,” laughs Chatterjee. He remained a bachelor all his life. He lives alone now, with some family members living close to him.

He quit his job too, after a promotion, as he could not manage the greater responsibilities and keep practising. Being in the game itself was tough. Table tennis was never a star sport.

“I left my job in January, 1945. On January 13, 1947, I would join my next job at Indo-Burma Petroleum, where my father also worked, and from where I would retire,” he says. “But in March, 1946, I enrolled at YMCA Chowringhee. It was the best place for table tennis, along with the College Street YMCA.” The best five years of his life followed, to end rather drastically.

He remembers with great pleasure the “historic” tournament held at the University Institute Hall in Calcutta in 1947, “between December 22 and 31”.

“It was the first time a reigning world champion, the Czech player Bohumil Vána, was participating at an Indian tournament.” Vána’s forehand was a legend. In a match, Chatterjee and Vána were even for long, till “19-19”, but Vána won at “21-19”, says Chatterjee, recalling every score.

“We could not organise enough matches those days because of the price of the balls. They cost Rs 60 a dozen,” he says.

A few months earlier, India had become independent, which had brought its own trauma. Returning from Puri a few days after Independence, Chatterjee had seen the body of a riots victim being eaten by vultures in front of Government House (Raj Bhavan).

In 1948, Chatterjee became the Bengal champion, and also won two other titles with the singles. In 1949, in an exhibition match in Batanagar, he met reigning world champion Richard Bergmann, an Austrian-British player. Chatterjee gave Bergmann grief and was ahead in the game at “17-13”, but Bergmann won at “21-18”.

He is very clear-sighted about his strengths and weaknesses.

“I would have been ranked between No. 8 and No. 10 in India if there was ranking system then,” he says. “My defence was weak. There were better players than me in Bengal itself, such as my friend Kumar Ghosh and Tej Bahadur Kichlu. But my forehand had class,” he says.

Talent is not the everything, however. In 1949, Chatterjee found himself inexplicably excluded from the India team. He and others were convinced that he deserved a place.

“I came back home and tore up my racquet in front of my mother and then burnt it. I was so hurt.” Though he represented Bengal at Colombo the next year, he decided not to play at major tournaments any more.

But not everything is winning and losing. Among his friends, Chatterjee counted another world champion, British-Hungarian player Viktor Barna, who became a mentor. Chatterjee remembers Barna as a warm, generous person, whom he could interview once at length at Grand Hotel, Calcutta, just walking in. For years, Barna kept sending high quality racquets to Chatterjee.

Chatterjee considers Barna’s interview one of his best pieces. The best piece he has written, says Chatterjee, is one about Shri Ramakrishna, whose devotee he is.

Among Chatterjee’s other friends are also the numerous younger people that he coached and mentored. He was a well-known referee and umpire. He proudly mentions another close friend, filmmaker Hrishikesh Mukherjee, his classmate. They were in touch always.

Chatterjee has left his major trophies and all his writings, in five bound volumes, with his grandniece, in case anyone is interested.

By the way, he is also a champion bridge player, which he started playing at 53. First auction bridge, then contract bridge.

He is up for a tournament right now.