Cholera introduced city grids and underground sewerage systems that dictated streets above them be straight and wide. The third plague changed door systems and threshold heights. The aesthetics of modern architecture — flat roofs and balconies — were dictated by the menace of tuberculosis. It is likely that Covid-19 with its new norms and altered living patterns will impact urban planning and architecture.

Final-year students of École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Paris La Villette were in Calcutta in January for three weeks for the Indo-French Workshop 2020. The workshop, themed Learning from Indian Cities, was organised in partnership with the Bharati Vidyapeeth College of Architecture in Navi Mumbai and Thiruvananthapuram’s College of Architecture.

The students observed up close some thickly populated areas of north Calcutta with the aim of offering architectural solutions to enhance living and working conditions. Post the corona outbreak, three of them submitted design interventions — short, medium and long-term — for Chitpur Road neighbourhoods.

Urban conservationist Kamalika Bose, the local resource person for the supervised project explains the choice of place. She says, “Chitpur, with its intricate network of bazaars, is reliant on migrant workers. Labourers, artisans, porters come from neighbouring states, many of who headed home when work suffered during the lockdown. Prolonged lockdowns slowed economic activity along Chitpur.” She continues, “This design project merges socio-economic factors with spatial strategies to shape a more resilient and habitable Chitpur Road in the immediate two-year period. These are also scalable, adaptable models that can be replicated in similar sites across Calcutta.”

Faculty member at École Claudio Secci says, “Occupations and economic vitality are the strength of Indian old city cores… If we ensure that occupations thrive, then inner cities like Chitpur can survive well.” Secci, who is one of the project supervisors, also tells The Telegraph, “The pandemic has spotlighted the poor conditions of the physical environments that support traditional economic activity and the lives of workers. Therefore, we have a double crisis on Chitpur Road — the bad conditions of its buildings and the fragility of the occupations. That is what we have addressed in this project.”

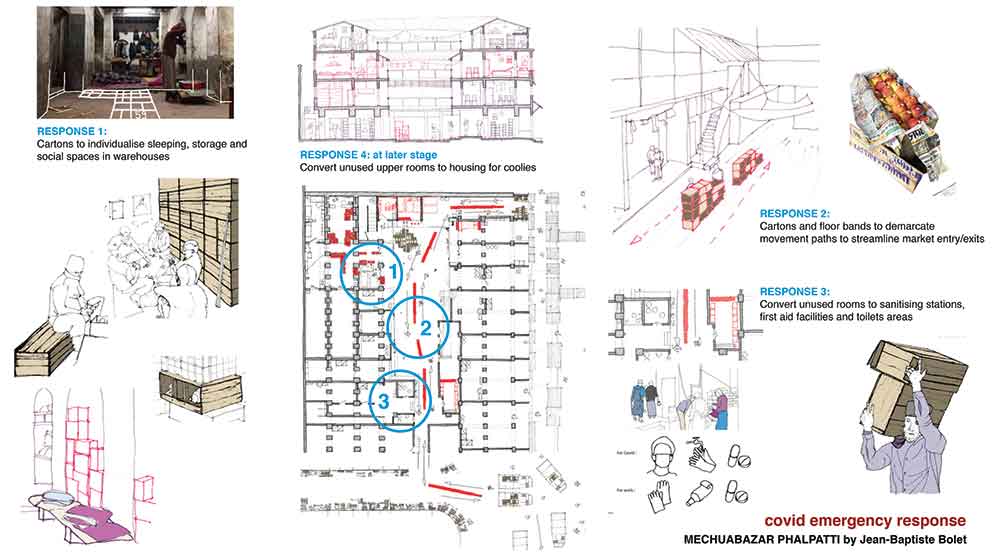

Mechuabazar Phalpatti

Site summary: Set up in 1825, it employs 1.5 lakh informal workers. The phalpatti, or fruit market, congests every building and spills onto the street. Covid-19 has diverted many trading activities to Santragachi in Howrah, providing an opportunity to reassess the market’s carrying capacity, reduce operations and manpower.

Proposal from Jean-Baptiste Bolet: Fruit cartons can be used as dividers to create sleeping spaces for labourers who do not have dedicated housing. Various configurations of wooden cartons could be used as beds, seating, storage, partitions and full-height space dividers to create cubicles and enable social distancing. Cartons along with flooring bands can also be used to control flow of people. As activities from the upper storeys of warehouses shift out in the long term, those spaces can be converted into dormitories for labourers.

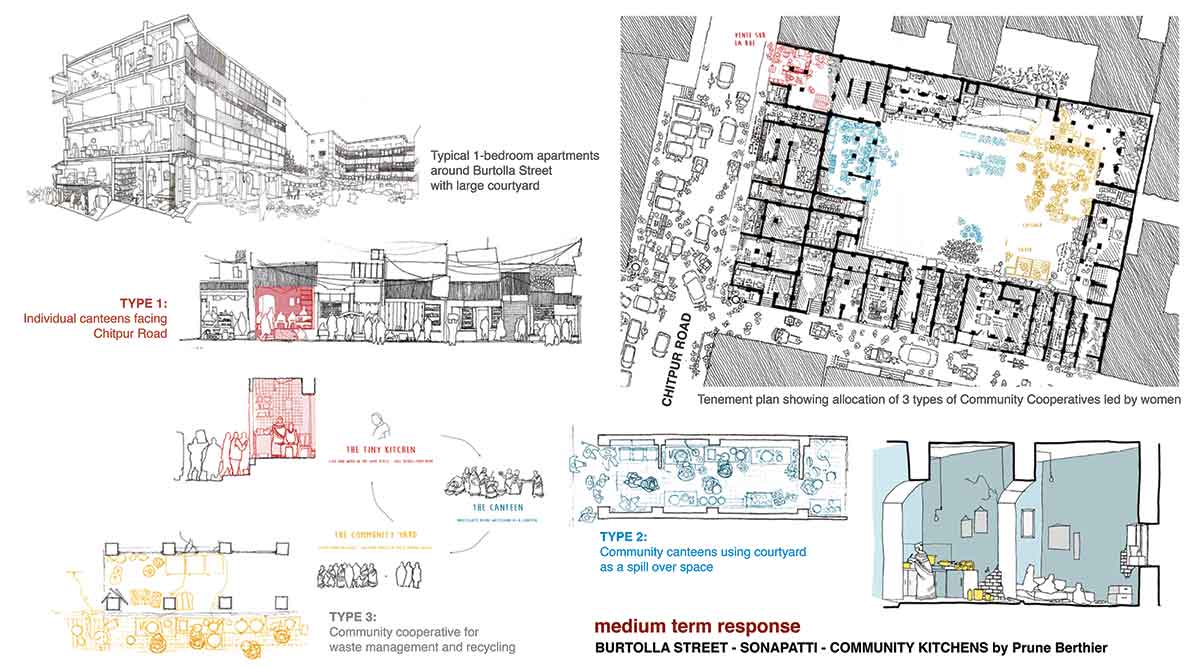

Burtolla Street Sonapatti

Site Summary: North of Mechuabazar, the area consists of four and five-storey tenements built in the 1920s. Each has 20-25 rooms on the ground floor, skirting the courtyard. Each of these 200-400 square foot rooms serves as karkhanas and gaddis. First floor upwards, there are 15-18 one-room tenements with common toilets on each floor. They house lower middle-income families.

Proposal from Prune Berthier: The large number of karigars and workshop staff eat at roadside stalls and informal eateries in Chitpur. This leads to crowding and littering, especially dangerous in Covid-19 times. Given the recent economic distress and job losses for many families here, as a medium-term intervention, community canteens are proposed in unused courtyards and vacant tenements. These could be run as co-operatives by women of the area.

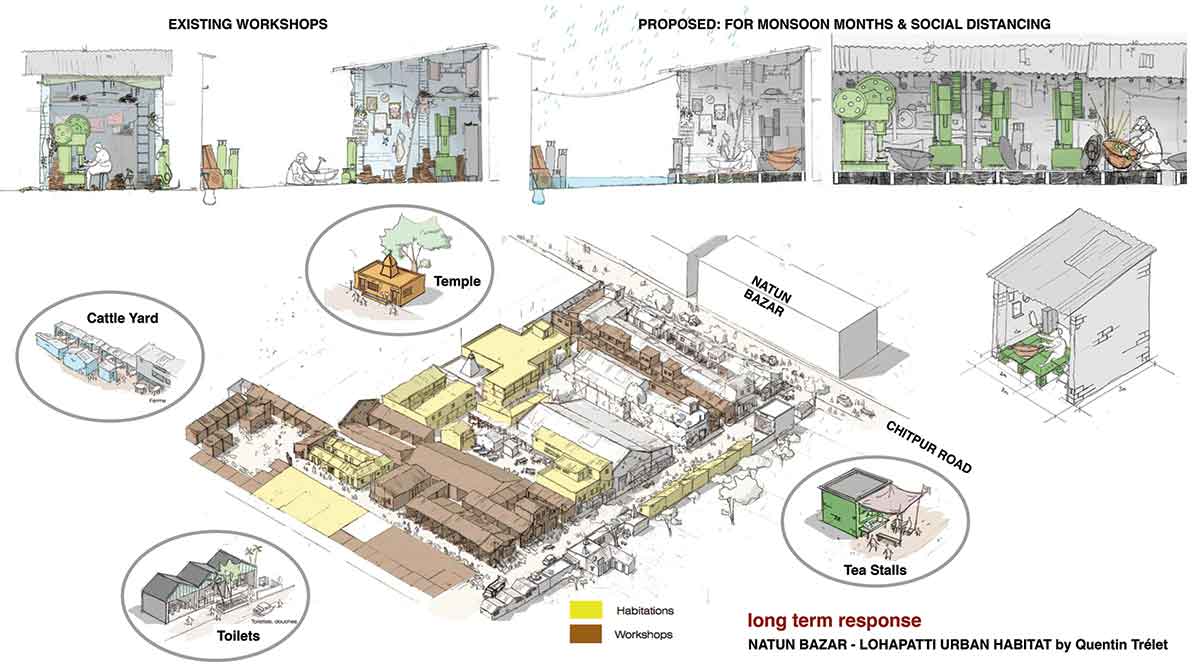

Natun Bazar Lohapatti

Site Summary: Iron market dating back to the 1890s. In the beginning it supplied metal utensils and equipment for the sweetmeat industry, but has diversified ever since. The skilled workers are migrants from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh who spend 11 months a year, contribute to the local economy, and yet live in abysmal conditions.

Proposal from Quentin Trélet: Workshop interiors are dingy, so workers use the bylanes and open area for cutting, shaping and welding metalware. This leads to waterlogging during rains. To avoid, create a temporary raised metal floor for workshops and add larger windows. This way they can work indoors, maintain distancing and be productive despite rains. In the longer run, segregation of live-work areas should happen. This will secure workers and their families from the dangers of metalwork, eliminate noise and waste strewn around and improve quality of life.