American Indologist and Sanskrit scholar Wendy Doniger had arrived in Santiniketan in August 1963 at the age of 22 to study Bangla and Sanskrit.

She made a number of remarkable friendships about which she wrote back to her parents. In January 2019, when she retired from the University of Chicago, where she was the Distinguished Service Professor of History of Religions, and was clearing her desk, she came across a bunch of letters that she said “came to her as part of a tidal wave of books and other things” after her mother died.

Reading excerpts from those letters at the virtual Bengal Library Talk last month, Doniger described Santiniketan as a sort of “finishing school” for Bengali girls. “In the evenings, girls sang in Sangeet Bhavan, sketched and danced. The afternoons were filled with children’s voices as there were no classes then. The evenings were cool and everyone made tea for everyone else. Santiniketan was a retreat from the city jungle in every way,” she said.

Doniger came to love Santiniketan because of its Indianness, of the constant sound of songs where ashramites woke up at 5am to sing, of the familiar faces everywhere, of the personal tutoring and saturation of Rabindranath Tagore. She talked of the girl who taught her Bharatanatyam in exchange for language classes in German, who was also a sculptor. She recalled how she was asked to teach her friends the song ‘Oh, you can kiss me on a Monday’ from the film Never on Sunday.

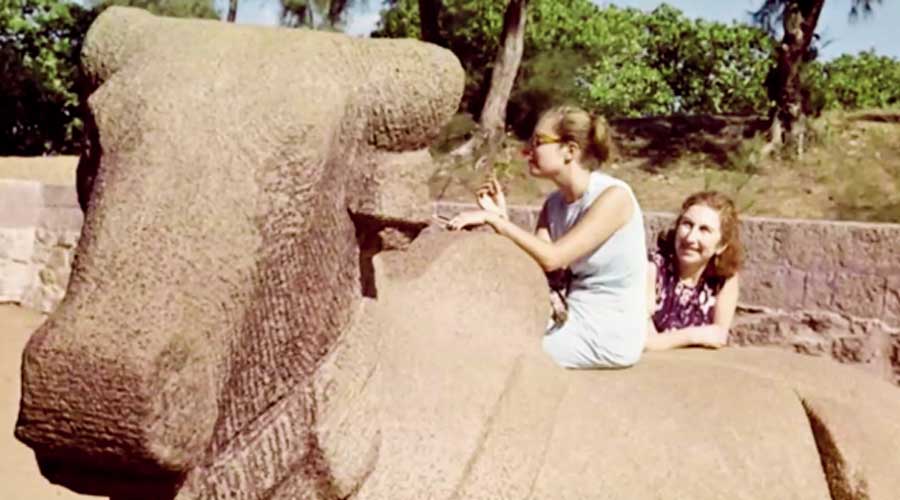

The American Indologist shares the picture during the virtual Bengal Library talk on her days in Santiniketan. The Telegraph

Doniger liked the slow-pace of life at Santiniketan, where one could enjoy life and where leisure afforded the study of scriptures and telling stories. “Bengalis always nibbled on something, whether it was betel leaf or sweet.” She remembered having dinner sitting cross-legged on the floor with a picture of Stalin over her. She met a man who had 8,000 books in his living room and Doniger tested him by randomly choosing a book and opening a page, which the man recited for her from memory.

Talking of the people she met on the train to Santiniketan, Doniger recounted how one Jyotindra Maity enacted the Ram Leela. “He danced the lines with his hands,” she described, adding: “if you tied his hands, he would become mute”. She would be brought tea on a running train, “the man would balance a tray on one hand dashing into the compartment as the train left a station”. Then there would be those who would chant the Geeta in the morning. People would climb in through windows and sit on luggage racks. Bus journeys, too, were similar with people hanging from every inch of space available yet the bus would go off route to reach a traveler his destination, she said.

Doniger spoke with great affection of her two women friends. One was Chanchal “whose mother cooked for her and brought her milk at night, which she would ensure she drank”. She narrated how the mother would bathe every time the shadow of a person from a low caste fell on her; Chanchal would run around her kitchen touching everything and her mother would then wash everything, she said. Doniger’s other friend Mishtuni Roy sang folk songs and recited Robert Frost and Emily Dickinson. Later in life, Doniger met Mishtuni at Oxford where she was with her husband.

The scholar spoke of meeting Jamini Roy at Santiniketan and buying a painting of his for 30 dollars. Calling him the greatest modern Indian painter, the Indologist wrote: “He paints with fervour and his paintings are basic to all people. They are purely Indian.”

She also met sarod player Ali Akbar Khan and described him as “he is to sarod what Ravishankar is to the sitar”.

These magical cross-cultural encounters, Doniger said, were made possible “by my youth, my optimism, my mad love for India and in part by the youth of the country, so newly freed from the colonial yoke”.