The framed logo, designed elegantly by Ramananda Bandyopadhyay, is a human head in the traditional Bengali style of bold and curved outlines. Looked at closely, the features of the face are revealed as the letters “a” and “t”, fused together. The logo, hanging next to a door, announces a rather unusual enterprise: an archive of Bengali theatre.

It is called the Academy Theatre Archive and has been set up on the first floor of a residential building at Netaji Shubhas Road, Howrah, by Devajit Bandyopadhyay, 66, a well-known performer of Bengali theatre songs. The archive is one large room and Bandyopadhyay conducts a tour around it, which turns out to be a mini, but grand journey into Bengali theatre.

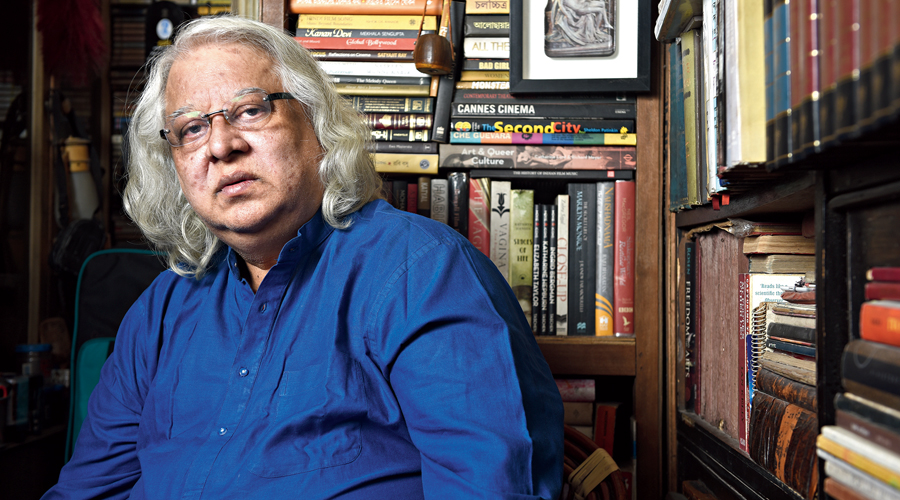

Through the years Bandyopadhyay has collected about 30,000 books, many from the nineteenth century or even earlier, and 30,000 gramophone records, a substantial part of them of theatre songs. The collection lies spread between his Howrah archive and his south Calcutta home, where his study looks like a tiny museum crammed with bookshelves that move on wheels, so that humans can move about.

Bandyopadhyay has a huge, impressive list of first-edition books and first or early records of Bengali songs, among other things. And every object around him has a story, and you almost hear it buzzing, and then Bandyopadhyay tells it. He is a natural storyteller, and one story leads to another, and you land softly and pleasurably into depths of the world of old Bengali theatre and performance.

It is a remarkable, fascinating and strange world, more so because unlike writing or the visual arts, which are there in front of us, often in their original form, live performance gets lost. In some way, even if it recorded. In addition popular entertainment changes its medium much more than the other arts and especially from the point-of-view of our social media-saturated times, the age of early Bengali theatre, though barely 200 years old and centred in Calcutta, looks unfamiliar. But it is, if we quote a leading playwright of all times anachronistically, “a brave new world”: of a performing art rendered in the language of the land, taking shape during colonial rule but being formed by influences from all over.

Bandyopadhyay starts at the beginning, at 1795, with Gerasim Lebedev, the Russian scholar-adventurer who ended up starting modern theatre in Bengal. Through a series of extraordinary events, and with some help, he translated two European plays into Bengali, one of them as ‘Kalpanik Sangbadal’. These were the first Bengali plays performed on a proscenium stage, which was also introduced by Lebedev here, and the plays were staged at the “Bengally Theatre” in Domtala, later named Ezra Street. Lebedev used songs from Bharatchandra’s Vidyasundar, the long poem on a love story, written between 1752 and 1758, says Bandyopadhyay. He has a copy of the early editions of Lebedev’s plays, and also a scanned version of Bharatchandra’s poem, which he obtained from the original punthi (manuscript) at Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris. He also has an 1817 edition of Vidyasundar.

The collection contains the first edition of Dinabandhu Mitra’s play Nil Darpan, about the savagery of the indigo trade in Bengal controlled by Europeans. This was the first play to be commercially staged by Bengali theatre pioneer Girish Chandra Ghosh in 1872. Bandyopadhyay has a first edition copy of Amar Katha, the autobiography of Nati Binodini, the actress who was mentored by Ghosh and made his plays memorable.

Music notations form a bulk of Bandyopadhyay’s collection, much of them of theatre songs. He has the earliest notation prints of Kshetramohan Goswami and Krishnadhan Bandyopadhyay, who worked with the production of Michael Madhusudan Dutt’s plays. “As well as those of Shishir Kumar Ghosh, Sourindramohan Tagore, Dakshinamohan Sen, Manmathanath De, and of course of Jyotirindranath Tagore, to Rabindranath Tagore to Upendrakishore Roychowdhury.”

His collection of gramophone records go back to the first decades of the 20th century. He proudly refers to a record of the songs of Banabiharini, who had acted as Nitai with Binodini as Chaitanya in Chaitanya Leela (1884). Other records include those of Danibabu (Surendranath Ghosh, Girish Chandra’s son), Shashimukhi and Ardhendu Sekhar Mustafi, Shishir Bhaduri, singers Gauharjan, Krishnachandra Dey, Angurbala and Kanandevi, most of them singer-actors. “One of the records has Bertolt Brecht speaking,” he says.

The first edition of nineteenth century jatra palas, such as Akrur Sambad, and several palas of Krishnakamal Goswami and Motilal Roy are a part of the archive.

A piece of music notation, in fact, had inspired Bandyopadhyay into archiving. He was in Europe in 1986, and on stage he felt encouraged to perform songs from Bengali theatre. The same year in London he was invited to perform by the BBC, where they meticulously checked the notation of the song he was about to sing by consulting Sourindramohan’s version. Bandyopadhyay was tantalised by the BBC library.

“That is how the idea of an archive began,” he says. How he collects his materials is another story. But music has ruled his life, for which he had to make difficult choices.

His father, a well-established chartered accountant and a resident of Howrah, wanted Bandyopadhyay to follow in his footsteps. Bandyopadhyay grew up in Howrah and studied B.Com. (Honours) at Shibpur Dinabandhu College in Howrah and took up accountancy and auditing work. But by that time he had already fallen for music.

He had trained under stalwarts of Rabindrasangeet (which he called Rabindranather gaan, a less reverent description of Rabindranath Tagore’s music) from the early 70s. From 1975, he was training under Ustad Sagiruddin Khan, internationally acclaimed sarangi player, who changed his relationship with music. “I realised commerce and music do not go together,” says Bandyopadhyay. He began to move away from his father, though he always remained close to his mother, who encouraged him. The archive, however, is housed in a flat that he received as his share of family property.

In 1990, he left home. He was already focusing on the music of Bengali theatre. In 1995, he began his Ph.D. on Bengali theatre music at Jadavpur University and completed it within a year.

The archive includes musical instruments — a 300-year-old veena, sitars, sarods and sarangis, including Ustad Sagiruddin Khan’s, gramophones, cameras and about 4,000 posters, starting with the posters of Naramedh (1932, record play). “Theatre cannot, of course, be studied in isolation,” says Bandyopadhyay. No arts, no discipline can be. But he talks about the special relationship between theatre and Indian cinema.

“We must remember that theatre here was the popular entertainment form for a long time. Common people paid money to watch plays. And theatre songs were the popular tunes. They were also sung by prostitutes as entertainment for their guests,” he says.

Songs in Indian cinema is a feature borrowed from theatre. And cinema, theatre and fiction have traditionally shared a basic structure, of the narrative. “Cinema in Bengali was called ‘boi’, a book,” says Bandyopadhyay. A film was being compared to the novel. “Indian films have never been able to discard the narrative.”

The books are mostly in Bandyopadhyay’s study and the bigger items at the Howrah archive, which is obviously work in progress. The posters need to be hung better and the other objects — imposing gramophone players, an old sitar with intricate carvings — need better display. The lockdown stalled the work, says Bandyopadhyay. He feels that the state should encourage such projects more, also financially. “It’s my life’s work,” he says, looking around.