American entrepreneur and venture capitalist Nick Hanauer recently said that if he and Jeff Bezos had started Amazon.com in a poverty-stricken corner of Africa, there would have been no job creation because there would be none to buy the stuff from Amazon.com.

The India story may not be as bad, but with consumption growth facing headwinds because of factors ranging from high food inflation to low real incomes, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman attempted an eyeball-grabbing measure to boost consumption demand in her eighth budget.

The JNU alumna proposed to put more money in the hands of the “middle class” by offering personal income-tax relief. There will be no tax liabilities on people earning up to ₹12 lakh (₹12.75 lakh for the salaried, thanks to a deduction of ₹75,000).

This proposal was probably the only tangible measure to fulfil any of the five major objectives Sitharaman had outlined at the beginning of her 80-minute budget speech.

“This budget continues our government’s efforts to accelerate growth, secure inclusive development, invigorate private sector investment, uplift household sentiment and enhance (the) spending power of India’s rising middle class,” she had said.

That the government is banking heavily on the private sector and the middle class for demand creation became clearer towards the end of her speech: she said democracy, demography and demand were the key pillars of the journey towards a “Viksit Bharat”.

A closer look at the realities of the Indian workforce, however, suggests that Sitharaman has thrust a Herculean task on ordinary Indians with her direct tax proposals.

Numbers shared by the Central Board of Direct Taxes suggest that about 7.54 crore Indians filed tax returns in 2023-24, of whom only 2.8 crore individual taxpayers made a positive contribution to the nation’s income-tax kitty.

As a sizeable proportion of this population is urban and earns decent salaries, its marginal propensity to consume — the proportion of an increase in income that a consumer spends on goods and services — is likely to be low.

This means the impact of the tax cuts on this segment’s consumption spending may not have the kind of multiplier effect Sitharaman has in mind.

If kick-starting growth was her main objective, she should have done something for the majority of the Indian workforce, who have traditionally remained outside the tax bracket. Government data reveal that a sizeable proportion of the country’s about 59 crore workers experienced a dip in income in recent years.

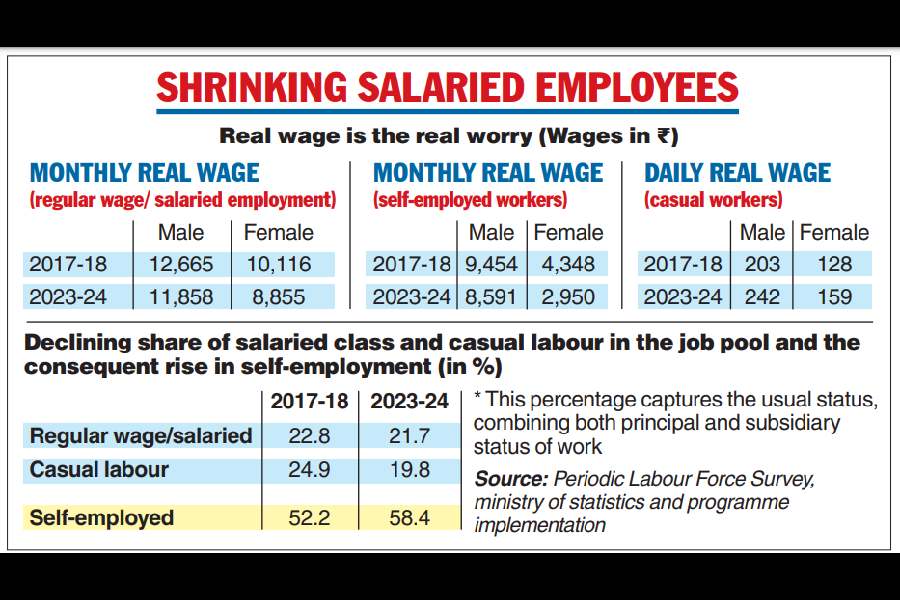

For instance, the average real monthly incomes of those who earn regular wages or salaries have fallen between 2017-18 and 2023-24. Ditto for the self-employed, who include kirana store owners, farmers and food vendors.

Sitharaman may seek solace in the marginal rise in the average daily wages of casual workers, but the levels are much lower than the laid-down minimum wages. Following last year’s revision, the minimum wage for construction, sweeping, cleaning, loading-unloading and unskilled work stands at ₹783.

Against this backdrop, Sitharaman could have considered reducing the indirect tax on ordinary Indians — by lowering excise or GST rates — to encourage them to spend more and spur growth. Higher government spending could have been explored, too, to achieve higher consumer-spending-led growth.

Dodgy data

Sitharaman claimed her direct tax proposals would slash revenue by about ₹1 lakh crore but projected an increase of over ₹1.8 lakh crore in income-tax collection in the next fiscal over the revised estimate for 2024-25.

She clearly expects a rise in revenue buoyancy, but achieving that target will be tough against the backdrop of economic growth sagging to a four-year low of 6.4 per cent, from 8.2 per cent last year. Although the Economic Survey has projected a growth rate of 6.3 to 6.8 per cent for 2025-26, India’s real GDP growth has mostly been lower than the Survey’s projections.

The budget documents reveal that Sitharaman has set the course for fiscal consolidation by announcing a fiscal deficit of 4.8 per cent for this fiscal, revised from the earlier estimate of 4.9 per cent, and setting a target of 4.4 percent for 2025-26.

Lower capital expenditure because of slower infrastructure execution in an election year and a ₹2.1 lakh crore surplus transfer from the Reserve Bank may have helped Sitharaman this fiscal. The fiscal consolidation roadmap, however, seems tricky amid the sluggish growth projections and the likelihood of the Eighth Pay Commission’s recommendations being implemented next year.