The 31 seats going to polls on Tuesday in the third phase will decide whether the new political equation put forth by the CPM and agreed upon, albeit reluctantly, by the Congress will change Bengal’s political landscape.

In their struggle for existence, the two parties have held the hand of a religious leader from the minority community who keeps the skullcap on his head, but talks about education, jobs, Hindu-Muslim and Muslim-Dalit unity and not the dogma that he spewed till even a year ago.

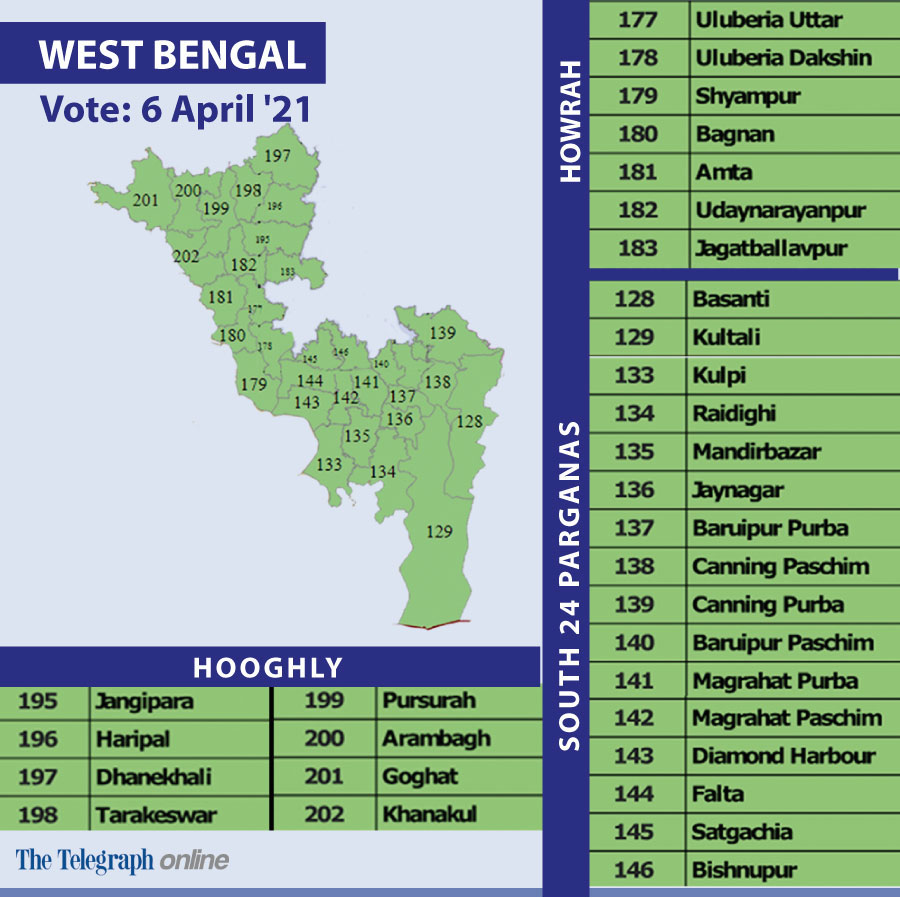

The next phase of polls in parts of South 24-Parganas, Howrah and Hooghly does not have the high profile focus of the second phase that saw Mamata Banerjee and Suvendu Adhikary locking horns in Nandigram. But it will be watched for Indian Secular Front (ISF) chief Abbas Siddiqui, the newest entrant in Bengal’s politics who has latched on to two grand old parties: the Congress and the Left.

Both have been out of power in Bengal for some time now. Congress had a brief taste between 2011 and 2012 when it was in alliance with the Trinamul. It is largely forgotten that the Bengal Congress despite its shrunken size had a role to play in putting an end to the 34 years of Left rule in Bengal.

The Muslim vote in Bengal is between 28 per cent to 30 per cent and since the 2008 panchayat polls, the vote has shifted from the Left to Mamata. The next phase of polling is crucial because it will decide whether the emergence of Siddiqui has made any dent in Mamata’s support base among the minority community. A shift in the Muslim vote could help the Left in retaining some of the vote share that it had lost to the BJP in the 2019 Lok Sabha polls.

The ISF has fielded 26 candidates _ Bengal has 294 seats in all _ after several rounds of parleys with the CPM. The adjustment has not been smooth with the Congress, for, a section of the party has been uneasy at sharing a dais with the religious cleric turned political leader.

“Do you want a government that will say something else to Hindus, Muslims, Dalits and Adivasis? Or, you want a government that will speak in the same voice and language to all the communities?” Siddiqui asked at a rally in Uluberia last week. The Left Front chairman and veteran CPM leader, Biman Bose, accompanied Siddiqui that day. Some CPM leaders have taken pains to “groom” Siddiqui and keep his focus on socio-economic problems and the importance of communal harmony in a state like West Bengal.

“However rough they play we will stop only after hitting the goal. Whatever needs to be done to form the government in 2021, we will do that,” said Siddiqui.

Indian Secular Front (ISF) leader Pirzada Abbas Siddiqui addresses a protest rally on the ongoing farmers' agitation, in Calcutta on February 23. PTI file picture

The ISF candidates' list for the 2021 polls is a mix of Muslims and Hindus, including Brahmins and Dalits. It has fielded candidates in Kulpi, Mandirbazar Canning East (South 24-parganas), Jagatballabhpur (Howrah), Jangipara, Haripal and Khanakul (in Hooghly) which will vote on April 6.

Elsewhere in these three districts, the ISF will campaign extensively for Left candidates.

In late November 2019, when the Pirzada was toying with the idea of a political party, Siddiqui had sent out feelers to all major political parties in Bengal, barring the BJP, seeking an electoral alliance or adjustment. It so happened that both the CPM and the Congress, who had then made up their mind to reignite the experiment of 2016, thought it prudent to include another partner, the CPM more welcoming than the Congress.

Traditionally, Bengal has never had a Muslim political leader with a pan-Bengal appeal. The Congress or the Left parties have had many a stalwart from the minority community. But none of those leaders, like, say, the Congress’ ABA Ghani Khan Chowdhury, were representative of the community in the strict terms.

In 2016, Mamata had picked up the Bengal unit chief of the Jamait Ulema-e-Hind, Siddiqullah Chowdhury, a bitter critic of the Left, who held sway over 900 Madrasas in the state and was believed to have a say in the community. For years, Muslim clerics made appeals from the Trinamul dais to vote against the CPM. At one point of time, Mamata had actively wooed Abbas Sidiqqui’s uncle Pirzada Toha Siddiqui. Siddiqullah went on to become a minister in the incumbent government. The decision then was considered a masterstroke.

Cut to 2021. Despite facing her most crucial election, Mamata ignored the overtures of Siddiqui, opting instead to rely on her connect with the community via her “service”. Whether that decison was to her advantage will be known only on May 2 when the EVMs are opened.