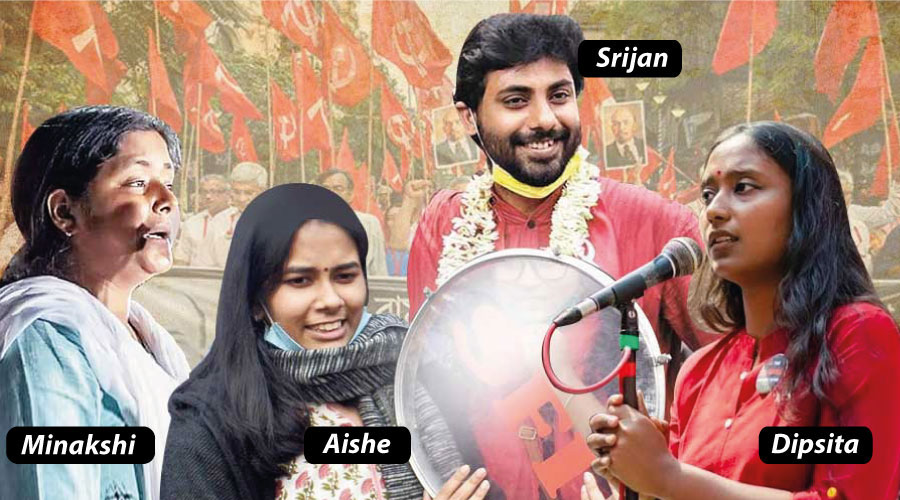

She is no fiery orator. She does not possess a trace of glamour. And almost everyone knows that her chances of winning are next to nothing. Yet Minakshi Mukherjee, the 33-year-old CPI(M) youth leader, has emerged as the unlikely new star of the 2021 Bengal elections. Videos of her quiet and determined campaign in Nandigram have gone viral; she is the most sought-after speaker at Left rallies throughout the state; and even those who have no allegiance to Left politics express a grudging admiration for the way she managed to make her presence felt in a high-pitched battle between Mamata Banerjee and her one-time protégé –turned-bitter adversary Suvendu Adhikari in Nandigram.

But for all the publicity that has come her way, Minakshi is less about an individual than a phenomenon: one among a host of new young faces that symbolizes the efforts of the Left to rejuvenate itself at a particularly critical historical juncture. And the response she is getting also reflects a bigger trend which has been largely suppressed in the din created by the big players in this election: that despite an all-out effort by both the TMC and BJP to make 2021 a bipolar contest, the CPM-led Samyukta Morcha remains a factor in the politics of Bengal.

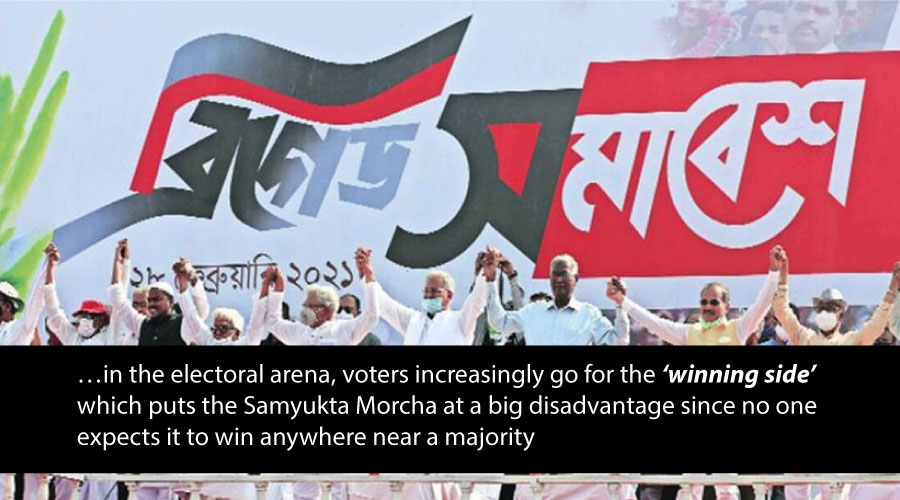

With the BJP taking full advantage of the anti-incumbency mood and lacing it with its patented tactics of communal polarization, and Mamata Banerjee fighting back with even greater ferocity after the Sitalkuchi violence and its aftermath, the space for a “third force” is certainly limited. Besides, in the electoral arena, voters increasingly go for the “’winning side” which puts the Samyukta Morcha (or “jot” as it is colloquially termed) at a big disadvantage since no one expects it to win anywhere near a majority.

Despite these factors, or perhaps because of them, the surprise element of this election is the number of people who seem to be looking towards the Left with more hope than despair. What makes it surprising is that both in perception and in reality, the once mighty CPM-led Left has been in a state of terminal decline – organisationally decimated by the TMC onslaught since 2011 and ideologically isolated after right wing Hindutva captured power at the Centre in 2014 and began rapidly spreading its tentacles into Bengal from 2016 onwards. The Left’s inability to withstand this twin assault has been reflected in the steady erosion of its vote share over the last ten years.

When it lost power and was reduced to just 40 seats in that cataclysmic election of 2011, the CPM alone still managed to get over 30 per cent of the vote. That plummeted to less than 20 per cent in 2016. It reached near rock bottom in the Lok Sabha elections two years ago when the party failed to win a single seat and garnered a meagre 6.34 per cent vote share.

The current assembly elections are taking place when the Bengal Left is at its lowest ebb ever. Apart from facing two formidable adversaries in the form of the TMC and the BJP, it is also the target of much criticism from secular and Left forces outside the state.

After the BJP’s spectacular performance in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections when it won 18 of the 42 seats with an over 40 per cent vote share, these sections felt that an enfeebled Left was in no position to check the BJP’s takeover of Bengal and should therefore back Mamata Banerjee. An intra-left debate between Left intellectuals and activists continues to rage in the virtual world of social media with many sharply critical of the CPM’s electoral tactics, including the setting up of the Samyukta Morcha.

The story is different in the real world. With Left supporters being the main target of TMC violence over the years, any question of backing Mamata Banerjee in the election was untenable. Left leaders insist that the “Aage Ram, Pore Baam” slogan which gained much currency during the 2019 polls started out as a pernicious RSS whisper campaign aimed at confusing the Left voter. The media and the TMC amplified it and falsely claimed that it was a sanctioned Left tactic. Whatever be the genesis of the slogan, the fact is that large sections of the erstwhile Left mass base shifted to the BJP in 2019 -- many because the Left was in no condition to protect them from TMC “terror” at the grassroots level.

Given this backdrop, Left activists point out, joining hands with the TMC in the name of “secular unity” would have only helped the BJP. The revulsion towards TMC’s corruption and violence is so great among Left sympathisers that such a tie-up would have ensured a further exodus of voters towards the BJP.

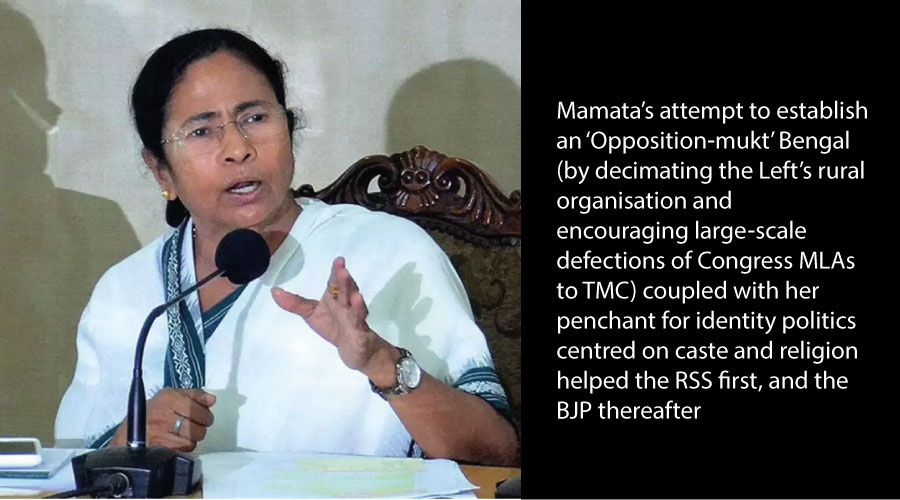

Ideologically too, there appears to be a big difference in how Mamata Banerjee is viewed in Bengal and her image outside the state. For BJP critics in the rest of the country, the TMC supremo is regarded as India’s most formidable secular icon – singlehandedly taking on the might of the BJP. In Bengal, leftists of all hues, claim the opposite. They insist that Mamata Banerjee facilitated the rise of the BJP in multiple ways. Her attempt to establish an “Opposition-mukt” Bengal (by decimating the Left’s rural organisation and encouraging large-scale defections of Congress MLAs to TMC) coupled with her penchant for identity politics centred on caste and religion helped the RSS first, and the BJP thereafter to take advantage of the new fault lines that appeared in the social and political fabric of post-Left Bengal, they contend.

But while the theoretical understanding of the need to fight the TMC as an essential element of the fight against BJP is one thing, to translate that into a meaningful exercise on the ground is something else altogether.

In order to do that, the Left has adopted new electoral tactics in this election of which the most talked about is the “youth factor.” At its state committee meeting in January, the CPM decided that 60 per cent of its candidates would be under 40 years and barring exceptional cases, it would not field anyone above the age of 60.

Minakshi Mukherjee apart, several of the youngsters such as former JNU students’ leader Deepshita Dhar in Bally, current JNUSU president Aishee Ghosh in Jamuria, state SFI secretary Srijan Bhattacharya in Singur, and SFI president Protikur Rahman in Diamond Harbour have attracted media attention. Youth is not the only factor that makes them different from the past. Many come from humble backgrounds such as Jhunu Baidya, the daughter of a sharecropper, who is fighting the Krishnaganj seat in Nadia district or Chandicharan Let, whose father runs a cycle repair shop in Bardhaman. “The truth is that after a very long time, a communist party has fielded communist candidates,” an old timer said.

The CPM has not just fielded young candidates but has also left it to the youth to plan and execute the campaign. That has lent a freshness and vivacity to the Left’s outreach seldom seen before. Social media has been flooded with funny memes, catchy songs and snappy videos that have reached out to a whole new generation in the state. The take-off on a peppy film number (Tumpa Shona) before the Brigade rally in February may have come as a bit of a shock to older comrades brought up on a diet of IPTA-era revolutionary songs. But Tumpa proved a monster hit and signalled the Left’s makeover efforts even before the list of candidates was announced.

The fielding of youth candidates, dismissed as a “publicity stunt” by both the BJP and the TMC, is much more than an electoral tactic. After decades of being in power, the CPM was seen as a party of the status quo, its leadership dominated by middle class bhadralok in starched white dhuti-panjabi even if the base comprised of poor peasants and workers. The crop of youth leaders who came up through mass movements in the 1960s and early 1970s were now old men. Those who joined later came to a party entrenched in power; when the terms “struggle” and “sacrifice” had long become empty shibboleths. It is a different story today. With the Left at its weakest and with little hope of any overnight recovery, the young men and women who have joined the party are seen to be driven by a sense of idealism and conviction rather than the opportunism and careerism of yore; they know that fighting elections is only the first step in a long hard journey ahead.

Another element of the new electoral tactic has been to focus on “livelihood” issues -- unemployment, price rise, hunger -- and steer clear of the emotive issues of religion and ethnicity that has come to dominate both the TMC’s and the BJP’s campaign.

The third, and perhaps most controversial, has been the decision to form the Samyukta Morcha that includes not just the Congress but also the Indian Secular Front headed by Abbas Siddique, the peer of the famous Sufi shrine in Hooghly district, Furfura Sharif. CPM supporters may have got over their old anti-Congressism, but the decision to join hands with an “Islamic cleric” has not gone down well with many of them. Even though the ISF seeks to be a multi-faith platform of the “downtrodden” including Dalits and adivasis, and Siddique’s speeches have focussed on secular rather than religious concerns, many Left sympathisers are uncomfortable with the decision. A CPM leader said the decision to form the “jot” was to make the third force more “visible, credible and winnable.” For now, it is has certainly made it more visible since Siddique (or Bhaijaan as he is known) has drawn huge crowds at every rally he has addressed. Whether it has made it more winnable won’t be known for another three weeks. And the credibility debate will continue for much longer.

So is the Left’s new experiment working? The answer is both no and yes – in that order. After innumerable conversations in street corners and chai shops dotted across small towns, villages and in the big city itself, it is clear that the bipolar contest between the TMC and the BJP is the central leitmotif of this election. The “jot” is a factor in less than a third of the assembly seats. Being a “factor” does not mean victory. And if the mood for “poriborton” assumes the dimension of a wave, the chances of winning more than a handful of seats in a three-cornered contest become even slimmer.

But elections are not only about winning. They are also about reaching out to people, making oneself heard, attracting new sections and converting hostility to goodwill. On that score, as we discover to our surprise, the campaign seems to be working.

Even in seats where the Left has no chance, the names of their candidates come up in random conversations. In Domjur, for instance, where heavyweight TMC minister Rajib Banerjee is now fighting on a BJP ticket against TMC’s Kalyan Ghosh, we get talking to Sayan Naskar and Biswajit Bag, two young men watching Mithun Chakroborty’s road show. They will probably vote for “change”, they say, but on their own bring up the name of Uttam Bera – the CPM/jot candidate in the seat. “Uttam Bera is a very good man. He is always there to help,” Sayan says. His friend adds: “The CPM candidates are very good this time: they are educated, disciplined, sober.”

It is a sentiment we come across in other places too. The words “shikhitto (educated)” and “bhodro (decent)” are used often. With the Left out of power for 10 years, the seething hostility towards the “Party” during the 2011 polls is now over. That Minakshi Mukherjee and Srijan Bhattacharya could campaign door to door for weeks on end in Nandigram and Singur respectively -- the two famous epicentres of the movement that felled the CPM -- is evidence of that.

What is more remarkable though are the many voices asserting that the Left has a future – even if the present is bleak. Biswajit Datta, who runs a chemist shop in Jadavpur, says that Sujan Chakraborty is a strong candidate but even he may lose in the “poribortoner jhod (the storm for change)”. But he goes on to add: “The Left will come back. They must, they should.”

Some distance away in Sonarpur, Pranab Ghosh says “Baam ashbe. Aaro unnoto baam aashbe. Ashtei hobe (The Left will return. A more rejuvenated Left. It has to).” And a retired schoolteacher in Champdani in Hooghly district concedes that “Baam prochur bhool koreche. Kintu shaasti o peyeche. Aabar notun hoye uthbe (The Left made many mistakes. But it has been punished too. A new Left will rise).”

Election strategists believe that the bulk of voters do not “waste” their vote on a party or alliance that is not a contender for power. This explains “wave” elections – a common phenomenon in other parts of India which has of late spread to Bengal too.

But perhaps because Bengal had a long tradition of firm loyalties (towards either the Left or the Congress), there are still people (numerically more significant than in other states) who do not go with the “winning side” regardless of any ideological convictions.

The rise of the BJP and the possibility of it gaining power have, in fact, drawn support for the “jot” from unexpected quarters. An elderly Sikh, at the wheel of an Uber taxi, does not know the names of any of the candidates in his constituency near Dum Dum. “Jo bhi jeetke aaye, Bangal mein bahut jhagde phasaad hone wala hain. (Whoever forms the next government, Bengal is in for turmoil)”. That is why, he adds, he will vote for the party he still associates with “discipline.”

The concerns of more politically conscious citizens go beyond the possibility of immediate post-poll turmoil. They envision a long, drawn-out ideological battle against the Right. A middle-aged couple in a Ballygunge highrise who were unsure about who to vote for at the start of the elections have decided to vote for the “jot” because TMC is incapable of fighting a prolonged ideological battle, now or later.

Sumit Chowdhury, a filmmaker and activist who was deeply involved in the movements in Singur, Nandigram and Lalgarh during the last term of the Left Front government, says there are many ideological differences within the various parties and groups that come under the broad “Left, secular, progressive” umbrella. These differences will remain and the debates will continue because that is what makes the Left a vibrant force unlike the monolithic Hindutva Right. But despite these differences, the time has come for a united battle to fight the new force that is taking over Bengal. “The real battle will start after May 2,” he says, a view echoed by several others in different parts of the state.

The CPM’s decision to field fresh new faces untainted by their years in power, and experiment with new alliances to break the communal binary that threatens to engulf Bengal may yield modest electoral gains. The real test, it is clear, lies ahead: will the new seeds from an old tree be smothered in a field overrun by the lotus? Or do they possess the resilience, the stamina, the strength to sprout and grow and flower in an increasingly inhospitable environment? These elections are just the starting point for a much bigger challenge.