In Bengal, cow slaughter is legal. So is consuming beef. It is eaten across the social spectrum. It is among the handful of states where that is still possible to do. But as naysayers are consolidating their position, the wind is changing; the ayes would rather be safe than flaunt a liberal gut. Last week, on Gopashtami Karyakram in Burdwan, Bengal BJP president Dilip Ghosh said, “On the holy soil of India... consuming beef is a maha aparadh.” He even said, “A few intellectuals eat beef on the road. I tell them to eat dog meat too, their health will be fine whichever animal they eat, but why on the road?” During his brief stint in Bengal during the last phase of the general elections this year, BJP national secretary Sunil Deodhar told The Telegraph categorically: “If the BJP comes to power, cow slaughter will not be legal.” In June, the Kolkata Beef Festival was first renamed Kolkata Beep Festival, and then cancelled following threats to the organisers. Deodhar had also said: “Where the majority does not want to eat beef, we want to bring in laws and where the majority wants to eat beef, we will convince them not to.” In Calcutta, beef is bought and sold and eaten to date. It might not be a majority thing, like eating fish is, but it is widely eaten and is also integral to the city’s menu — high table, low table. It is also as much about the eating as a way of being.

It is late afternoon, about 2ish, but a section of the meat market in central Calcutta is open. True, at that time of the day there are not too many customers, but the butchers are at it. Chopping, dicing, slicing, piecing, all with dexterity that is most likely generational. Should any outsider venture into the largish hall, they look up from chattering knives and ask, “Kya lenge?… What would you like?” One woman asks after the price of cuts of sutli kebab, longitudinal strips of meat. Rs 250 a kilo, comes the reply. Same for boneless. The regular pieces come at Rs 180 a kilo. A man with a smartphone keeps clicking photographs, but no one seems to care. The market remains open from 6 every morning to 7 at night.

Out of the market and across the street there is a whole row of eateries. Most of these places seem to run off regulars who work around the area. From the looks of it, some of the shoppers who venture in without a word are returning customers; they seem to know exactly what they want. “Ek plate pagla bhuna,” shouts someone. A section of the menu reads: beef bhuna, beef korma with egg, beef stew, beef tikia... If you are an obviously unknown or out-of-place entity, man or boy will sidle up to you and rattle off the day’s specials — chicken, mutton, egg. Only if you ask for gosht or bada — colloquialisms for beef — they nod in affirmation. Yes, it is available.

“Yahan har dukan mein beef milta hai (Here you get beef in every shop),” the man at the corner paan shop proffers with a yawn. These shops stand cheek by jowl with others selling momos and rolls and whatnot. In fact, the only places that are conspicuous here are those that wear their caveats on their signage — No beef served here.

The Calcutta Cook Book was first published in 1995. A culinary chronicle of travellers and traders — as described in the preface. The book contains recipes for Salt Beef, Tehary, Bhoonie, Baked Lasagne and the cut of meat is specified for each dish.

The recipes are not clinical listicles but come with tips and asides. The one for Salt Beef reads: “A piece of salted beef in the larder is an excellent stand-by for unexpected guests, packed lunch for office or with thin slices of marinated onions and cucumbers in salt in a mustardy sandwich.”

According to the footnote, it was the Dutch who salted meat in Baranagar in the 17th century. Reads the excerpt: “Calcutta has kept the Dutch tradition and if the process given is too troublesome, the Calcuttan will go to beef man in the New Market who will do a good job.” Recipes of the Tomato Farci or stuffed tomatoes and Potol Dolma or stuffed wax gourds have beef as a central ingredient. Then there is reference to the Buffath, a beef and vegetable stew of Portuguese extraction and a recipe from the notebook of Mona Benham, an Anglo-Indian woman.

Bunny Gupta is one of the co-authors of The Calcutta Cook Book. Says the octogenarian, “Beef was unheard of in our homes. But it was not as if no one ate beef outside home. There was a certain closeness between communities, people respected each other.” Ardhendu Dasgupta, who is in his 70s, remembers having bully beef or corned beef out of a tin as a child. His father had picked up the habit when he served in the air force during World War II. Dasgupta cannot remember if the neighbours or relatives knew and it certainly never came up at the grandparents’.

Gupta talks about how in the 1950s and 60s, barbecue was very popular and the steak was an integral part of the barbecue experience. The meat could be bought from New Market, Beckbagan or Park Circus. Restaurants such as Olypub, Olympia and Pelitis served a mean steak. The bones were used to make consomme. The clubs also served beef. The cookbook quotes a senior club member remembering one old-time favourite, Steak Romain. It goes: “A fairly thin slice of grilled beef, on top of that grilled ham, on top of that mushrooms and on top of that a good appetite.”

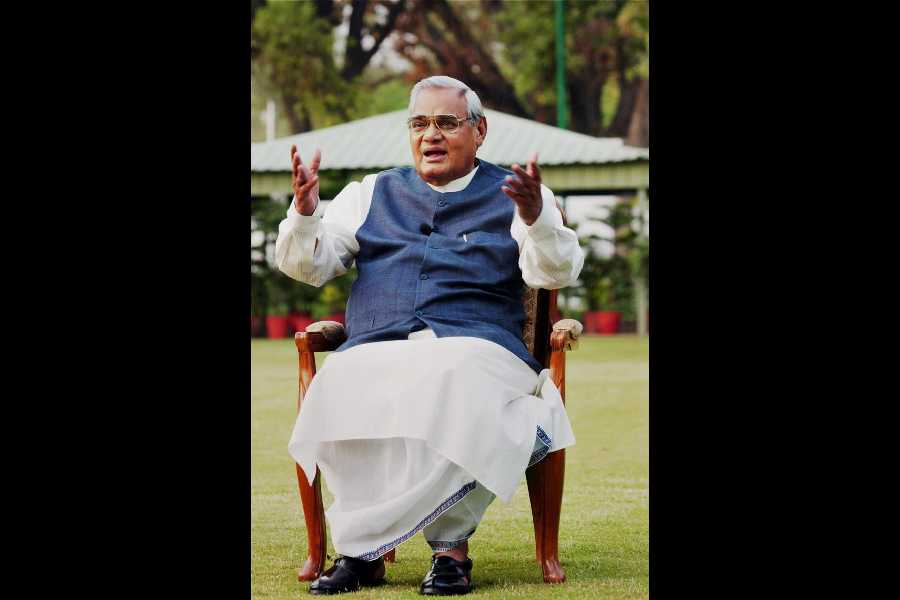

GUT FEELING: Lanes in central Calcutta that are still on the map of beef lovers in the city Subhendu Chaki

It was a matter of pride that the meat here, of humped cattle, was of superior quality. Now, things are different. Though a clutch of restaurants and clubs still serve beef, instead of boasts, denials pour in the moment the B word comes up. Disclaimers follow — buffalo, not cow, etc. etc.

Musician and food writer Nondon Bagchi talks about the 1970s and 80s. He says, “Most cooks, helpers and waiters [at these places] were Muslims. They wouldn’t have had a problem. Consumption of beef was accepted like any other form of community behaviour. It was not restricted to the elite but to people with an intellectual openness.” He adds, “Don’t forget that the Muslims ruled in Bengal. Then the British. And all were eaters of every kind of meat. So outlets selling what the ruling race ate was a common thing.”

It is 5 in the evening. The lane behind an iconic mosque in the heart of the city is recovering from its afternoon siesta. There is a thela with a huge pot on it. The signage reads: Salim’s Daleem. The man helming it puts cubes of meat into three katoris, plunges ladle into pot and splashes generous helpings of dal over each. Then comes the chopped green chillies, fried onions, chaat masala and lemon juice. Daleem? Isn’t that haleem, the rich, doughy dish made of, among other things, minced beef? The thelawala is mum, the elderly helper merely cackles and shakes his head from side to side.

Deeper inside the lane, dhaba-type eateries are prepping for the evening’s hungry tide. The first shop has a clay oven with a tawa bubbling with a red meaty gravy. The man standing next to it is kneading a mountain of silken dough. The blackboard in front reads: Beef Rs 60, Roll Rs 20, Sabji Gosh... “From now till 9 at night there is not a moment’s rest,” says the man with the long white beard who is coaxing tourist-types to try a freshly made pantheras — a kind of crepe stuffed with minced meat. It is chicken, he will tell you if you stare for too long. “I have long stopped serving beef,” he adds without making eye contact.

A few lanes away, bang in the middle of an old office para, there is a row of roadside stalls deep frying beef samosas, not conical like the regular samosas, but large golden semicircles with crinkly borders. There are nearly two dozen skewers ensconced by marinated meat. A daily-wager walks inside one and orders a plate of beef biryani; it costs Rs 30. A man in formals and an id card round his neck is wolfing down parathas with kebab. One paratha comes for Rs 4 and a plate of kebab is Rs 14.

At Rs 180 a kilo, beef is one of the cheapest meats, says Mohammed Ali Quraishi, president of the Calcutta Beef Dealers’ Association. The Tangra slaughterhouse, which he runs, used to butcher 300 animals every day. The number is now down to 100. He clarifies, “Only cattle that no longer produces milk is slaughtered.” After the cow-related lynchings, supply of cattle from Uttar Pradesh had stopped. According to Quraishi, the supply of cattle [to Bengal] from UP, Punjab and other far-off states by train had been discontinued by the Congress regime under Narasimha Rao. Says Quraishi, “All this has also meant reduction in supply of milch cattle for khatals. Milk prices have gone up.”

Bagchi had said that in the early 1960s, beef was Re 1 a kilo and mutton was Rs 6. Writer and educationist Ian Zachariah says beef was served in the hostel of a reputed boys’ school of Calcutta in the 1960s. He adds, “This bogey about eating beef is a political thing. It is doing a lot of damage to the country.” Bagchi expresses surprise when told about the cancelled beef festival.

In 1873, Rajnarayan Basu wrote Se Kal Ar E Kal, a comparison of the pre-English education days in India and the period that followed. He cites an anecdote about two Bengali men at Wilson’s Hotel. Gentleman A asks for veal. Not available, says the waiter. He proceeds to ask for beef steak, ox tongue, calf’s foot jelly. “No. Not that. Not that either,” come the waiter’s responses. “Don’t you have anything from the cow?” he says finally. Now, Gentleman B, who has been a spectator for so long, opens his mouth. “Just get him some dung,” he says exasperatedly.

Quoting Basu and invoking this anecdote, social scientist Partha Chatterjee said in a talk — it has since been printed and published with the title “Our Modernity” — “Many of Rajnarayan’s examples and explanations will seem laughable to us now. But there is nothing laughable about his main project, which is to prove that there cannot be just one modernity irrespective of geography, time, environment or social conditions. The forms of modernity will have to vary between different countries depending upon specific circumstances and social practices...”

Does eating beef make one modern? Or does shunning it make one a better citizen? You tell. No moral here, no story, only facts and a feeling gut.