As I write this the global death toll from Covid-19 approaches 9,000 and the total number of cases has breached the 2,00,000 mark.

The chief minister of Bengal has demonstrated war-like urgency in the battle against the virus, and we would do well to heed the Indian Prime Minister’s call for a voluntary curfew this Sunday, whether we choose to clap our hands while at it, or not.

Meanwhile, Calcutta has its first two Covid-19 cases imported by students from the UK.

This is clearly a red flag.

How many other such carriers are already in our midst, yet to exhibit symptoms, and infecting others? We do not know.

Official figures put the number of diagnosed cases in India above 200 at the time when this is being written, with four deaths so far. From the Chinese experience, it is likely that the number of undiagnosed cases in India is greater and waiting to explode upon us, as I shall illustrate later. Having worked in our healthcare system, there can be little doubt that our capacity to respond to a mass outbreak isn’t a fraction of what we have witnessed in China or South Korea. We need to take urgent steps now to prevent a disaster of the scale we have witnessed elsewhere.

A pandemic evolves in four stages. In stage 1, the disease is imported into a region from affected regions, as illustrated by the case in Calcutta. India is currently in stage 2, characterised by local transmission from positive cases. Stage 3 is defined by the disease spreading in the community. Stage 4 takes on the features of an epidemic with no clear end-points in sight, as already experienced by China and Italy.

Let us review the evidence we have so far to understand why we may be approaching stage 3 (or perhaps already in the midst of it) and what needs to be done to prevent it.

Data from China, South Korea and Italy show that the number of people infected with Covid-19 doubles every 3-6 days (doubling rate) once the disease is in the community. Roughly translated, this means that the number infected can increase 100 times in three weeks! The incubation period of the disease — the delay between infection and first onset of symptoms — is around two weeks. Moreover, data scientists have documented a further delay of approximately 11 days between the onset of symptoms and hospitalisation. Therefore, by the time that patients start to get diagnosed and hospitalised, levels of infection in the community will have already sky-rocketed. And 1-2% of them are likely to succumb to it.

The world’s most advanced and well-equipped healthcare systems in the USA and Lombardy (Italy) are either threatened or on the verge of breakdown, faced with exponentially increasing numbers of patients who require hospitalisation, often for weeks, and often requiring ventilatory support. There are simply not enough beds, and medical and nursing manpower is being strained beyond capacities. In Lombardy, doctors are having to perform heartbreaking wartime-like triage in hospitals to decide which patients to prioritise for admission and treatment, and who to leave behind to die.

On any given day there are more people milling about in Gariahat than you would find on the streets of the average town in Lombardy. Given our population, it is worrying to imagine what form a public outbreak could assume in our scenario.

Let us now look at infectivity. In the past few weeks social media has been swamped by people trivialising this disease by saying, among other things, that ‘common flu kills more people’. On average, the common flu has an R0 of 1.3. This means that each person (generation) with the flu would infect around 1.3 people, who form the next ‘generation’ in the chain of infection, each further transmitting the virus to 1.3 other people. If the R0 drops below 1, the disease stops spreading. If the R0 > 1, the disease spreads. For

Covid-19, the documented R0 so far outside China has been 2-3.

The Telegraph

To illustrate the difference in infectivity between the two diseases let us consider a numerical analysis published by Fast.ai, a leading institute on data science and deep learning — after 20 ‘generations’ of infection, an R0 of 1.3 would result in 146 total infections while an R0 of 2.5 would result in 36 million infections! Yes, let that sink in — 36 million.

However, R0 is subject to counter-measures taken to limit the transmission of disease. In China, it has already dropped below 1. Yet, that has been possible to achieve as a result of unprecedented measures taken by the Chinese government — a million people tested per week, entire metropolises put on lockdown, and the first Covid-19 dedicated specialty hospital built in six days!

Let us contrast this with the Italian experience. Millions of Italians were also put in lockdown, later extending to the entire country. However, these steps were taken only once millions of Italians already had sub-clinical infection. The differences in results are there for everyone to see. Following an unprecedented and aggressive response, China is already on its way out of the epidemic while Italy is struggling.

Italy, South Korea and Iran had time to take lessons from China and take necessary measures. They failed to respond quickly and effectively, thus paying the price for inaction. This is the most critical lesson for us — aggressive and uncompromising steps for containment must be initiated early in the evolution of the disease in stage 1 and 2, when the disease load is not yet apparent. Once community transmission is widespread in stage 3 the case load jumps in thousands, as opposed to single-double digits in the first two stages. That is when the game would likely go out of our hands.

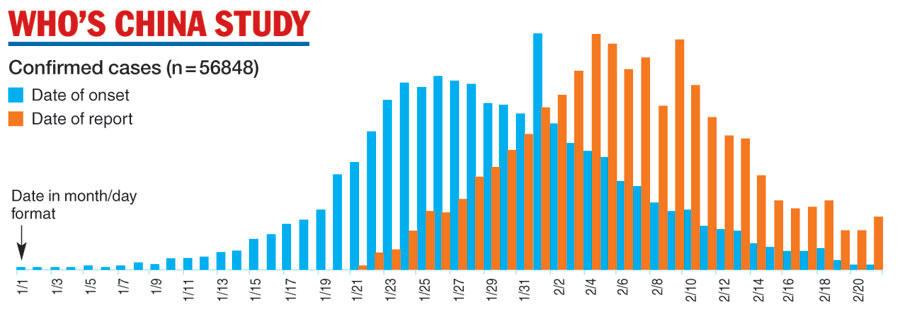

What do I mean by ‘when the disease load is not yet apparent’? Let us take a look at the above graph published on 24 February by the WHO-China Joint Mission on Covid-19.

This figure charts the pattern of progression of all cases in China till February 20, 2020. The bars in orange document the number of cases diagnosed by testing or admitted in a healthcare facility on the particular day. The blue bars represent the number of cases which were retrospectively found to have been present in the community on that same day by questioning diagnosed patients later on about onset of symptoms. We can clearly see how at the initial stages of disease progression the actual disease load in the community was far greater than what was diagnosed, day-for-day.

The graph also shows that later on, the actual case load started to decline in the community although patient numbers in hospitals had started to rise.

There is one lesson and one warning here.

First, once a public outbreak of Covid-19 takes place, sincere efforts at containment need to be sustained even in the face of disappointing results in terms of continuously rising patient numbers.

Second, the declining blue bars (actual community cases) are testament to the unprecedented efforts China was able to mobilise in the fight against this disease. It remains to be seen whether India, or others, can achieve equally impressive results.

What must we do now? We must break the chain of disease transmission in the community. That is all-important. Because, it is critical to ‘flatten the curve’ of disease progression.

This can only be achieved by widespread, voluntary public participation to contain this disease. Every individual who has the slightest option to stay at home or work from home must do so. Please remember that there are those who simply cannot afford to do this — daily wage workers, medical personnel, police, essential services, press, branches of administration etc. Please help to keep hospital beds and treatment facilities free for those who necessarily must go out to work, voluntarily risking themselves to the disease as many of them are direct spokes in the wheel of action against Covid-19.

If you must go out, practise social distancing from others, wash your hands frequently with soap and water for 20 seconds or use an alcohol-based hand sanitiser after every contact with any surface which may be potentially infected, wear masks where appropriate, and do not touch your face at any time. Avoid gatherings, sports events, religious melas, political meetings and pre-planned events.

“Don’t panic, stay calm” appears to be a favoured theme doing the rounds right now. It is good advice and makes every sense. But complacency should not be likened to calmness and panic must be recognised for what it is — a distant cousin to aggressive action.

Uniquely, the coronavirus has placed the bulk of the onus of fighting it squarely on the shoulders of the public. This is, in every sense of the term, a community disease. A public health problem. The biggest fight has to come from the public. Political will, administrative efficiency, and the front-line role of healthcare workers are crucial. However, there is no treatment, and no vaccine yet. Non-pharmaceutical, public health measures to prevent transmission followed rigorously by the public are key here. And the next 2-4 weeks will be decisive for our country.

Please also remember that if you are young and fit and get infected, you will likely suffer for a week and then recover. However, transmitting the disease to an elderly or immuno-compromised person could be fatal to them. That person may be a neighbour, friend, parent, or grandparent — and the burden to bear will forever be yours.

It is as though Covid-19 has put to the test existing gaps within the entire global public health infrastructure. But equally, a test of community spirit, of political will, of scientific prowess, self- discipline and optimism. It is far better to rise to the challenge now rather than once it is already too late. We need to look Covid-19 in the eye and declare “Sorry, Earth is closed today”.

Sources: WHO-China Joint mission statement on COVID-19; WHO COVID-19 Situation Report 59; US CDC; Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics, Harvard University; Fast.ai deep learning institute

The writer is visiting academic at Cambridge Endometriosis and Endoscopic Surgery Unit (CEESU); associate researcher at University of Cambridge Strategic Research Initiative (SRI) on Reproduction and research director at GD Institute for Fertility Research