The humanism of Mirza Ghalib is the need of the hour in India, an Urdu scholar said at a programme to celebrate the 19th century poet’s tryst with the city.

“Humanism is the essence of Ghalib’s work. He did not believe in barriers of religion, nation and past history. That humanism is most needed in present times, where you should consider yourself a human before being a Hindu, Muslim or Christian,” Shamim Hanfi, literary critic, author, poet and professor emeritus in the Urdu department of Jamia Millia Islamia, told The Telegraph at Calcutta Madrasah on Friday evening.

“Bas-ki dushvar hain har kaam ka aasaan hona / Aadmi ko bhi mayassar nahin insaan hona (It is difficult for every task to be easily done/For a man, too, being human is not easy),” quoted Hanfi from Ghalib to stress the “difference between being aadmi (man) and insaan (human)”.

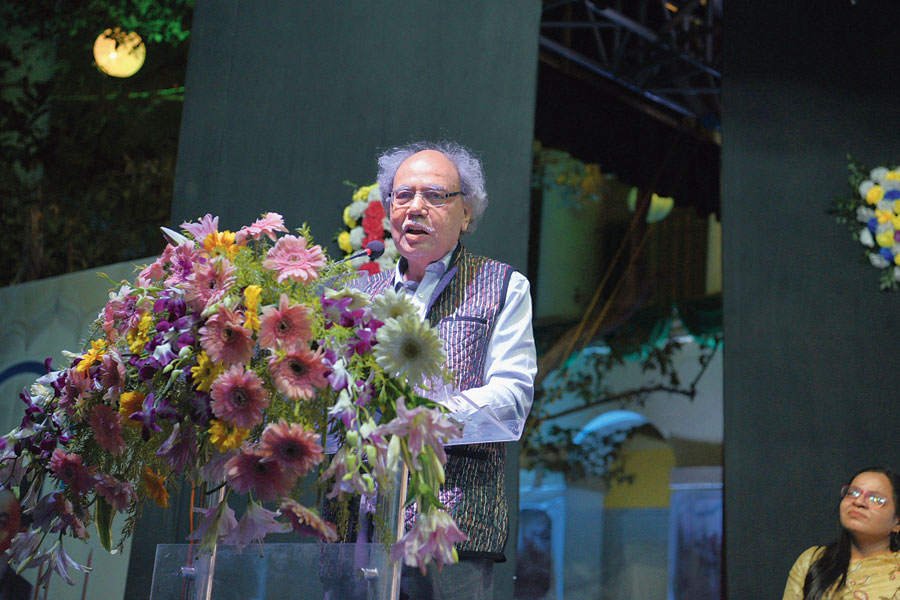

Hanfi, 82, delivered the keynote address at Bayaad-e-Ghalib (Remembering Ghalib), organised by Bengal Urdu Academy at Calcutta Madrasah Aliah University, in Taltala, on Friday to commemorate the 190th year of the poet’s visit to Calcutta. Ghalib had come to the city to negotiate his pension with the British masters and stayed here from February 21, 1828, to October 1, 1829.

Although the visit did not lead to a revision of his pension, Ghalib had found a new love in Calcutta. “Kalkatte ka jo zikr kiya tune humnasheen, ek teer mere seene mein maara ke hai hai (A mention of Calcutta by you, my friend, has pierced my heart with an arrow),” the poet had written.

Hanfi admitted to being in love with Calcutta as well. “Ghalib was not the only one in love with Calcutta. I am also smitten by the city,” he told the audience.

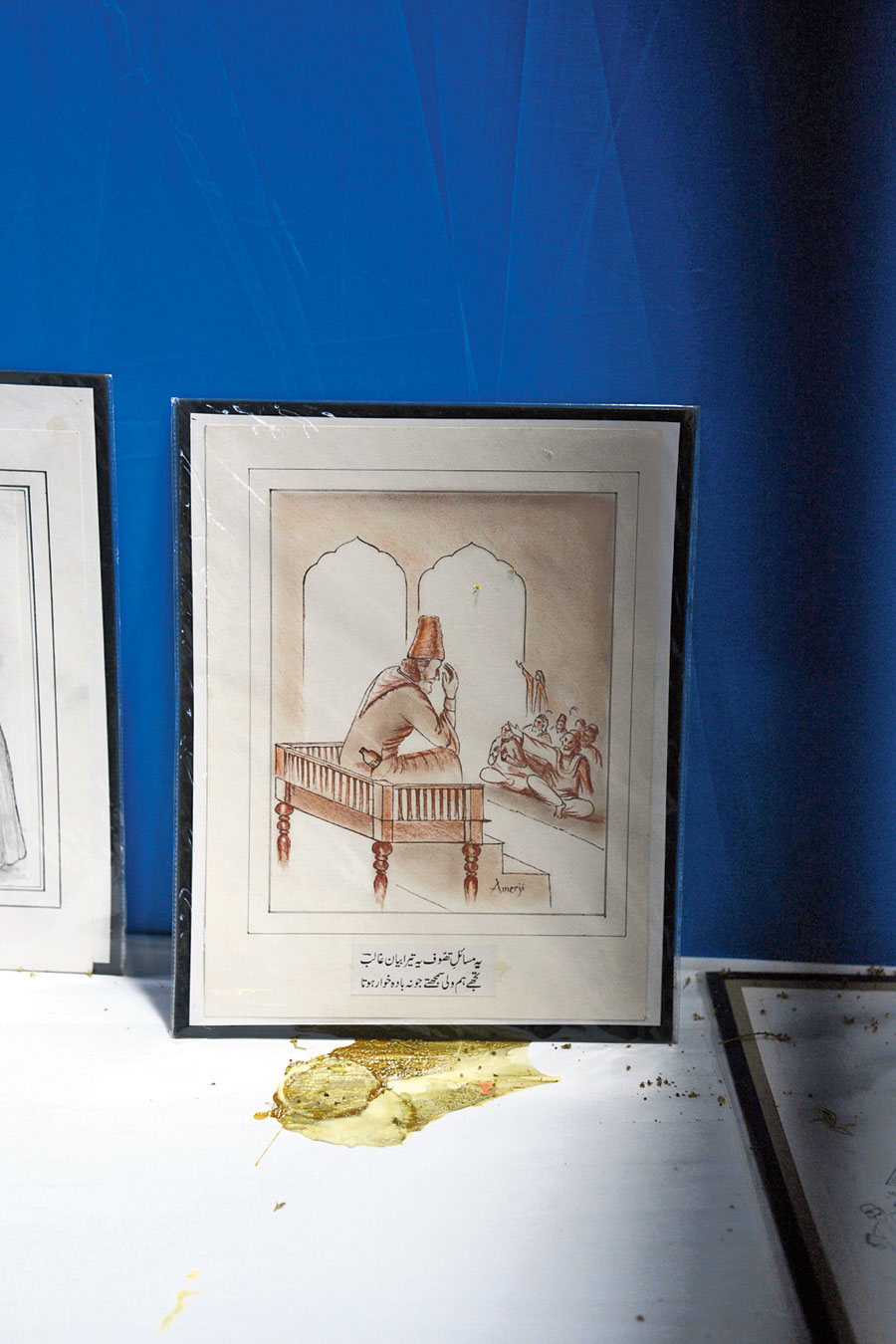

One of the pictures on display at the exhibition shows Ghalib seated in front of an audience, delivering what seems to be a sermon, a bottle peeping out of his pocket

Tagore’s warning about “dangers lurking in the corners” also found mention in Hanfi’s address. “In a speech at Jadavpur University in 1905, Tagore had warned how frantic nationalism and religious fundamentalism were waiting to enter our lives through invisible doors (chor darwaza),” he said.

“Ghalib did not believe in “isms”. He was not a religious man. He was agnostic in a way. He never took religion to be absolute and thought it was open to questions,” Hanfi added.

The scholar suggested that Ghalib was relatable because he never hid his vices. “He drank and gambled. That is what endears him to people. They can relate to him even after two centuries.”

A few metres from the dais, at an exhibition of paintings on Ghalib, a section was titled “wine, intoxication and humour”. One of the pictures on display had Ghalib seated in front of an audience, delivering what seems to be a sermon, a bottle peeping out of his pocket. The caption read: “Ye masail-e-tasavvuf ye tira bayan Ghalib/Tujhe hum vali samajhte jo na badahvar hota. (Oh Ghalib, your breathtaking interpretation of complex and complicated hidden meanings of mysticism! We would have believed you a friend of God, were you not a drink reveller.”)

The artist, Nooruddin Amerjee, said he drew inspiration from Ghalib’s love for wine and his writings.

Asked about the crackdown on Jamia Millia and the protests against the new citizenship regime, Hanfi said: “We respect the Constitution. The unrest in Jamia is because of that. The respect for the Constitution should not be eroded. The students of Jamia and the women of Shaheen Bagh are bound by the same thread.”

“The good thing is the movement is not communal,” he added. “At Jamia, Hindus, Muslims and Christians are sitting together. The NRC in Assam left out so many Hindus. This is not a communal issue.”

The festival, which ends on Tuesday, will include seminars, plays and mushairas on Ghalib.