A riveting discussion on a novel dealing with displacement, forced upon individuals and even entire communities by a degenerating biosphere, culminated in a general sense of gloom among speakers and listeners over a planet being pushed to the edge of an ecological precipice.

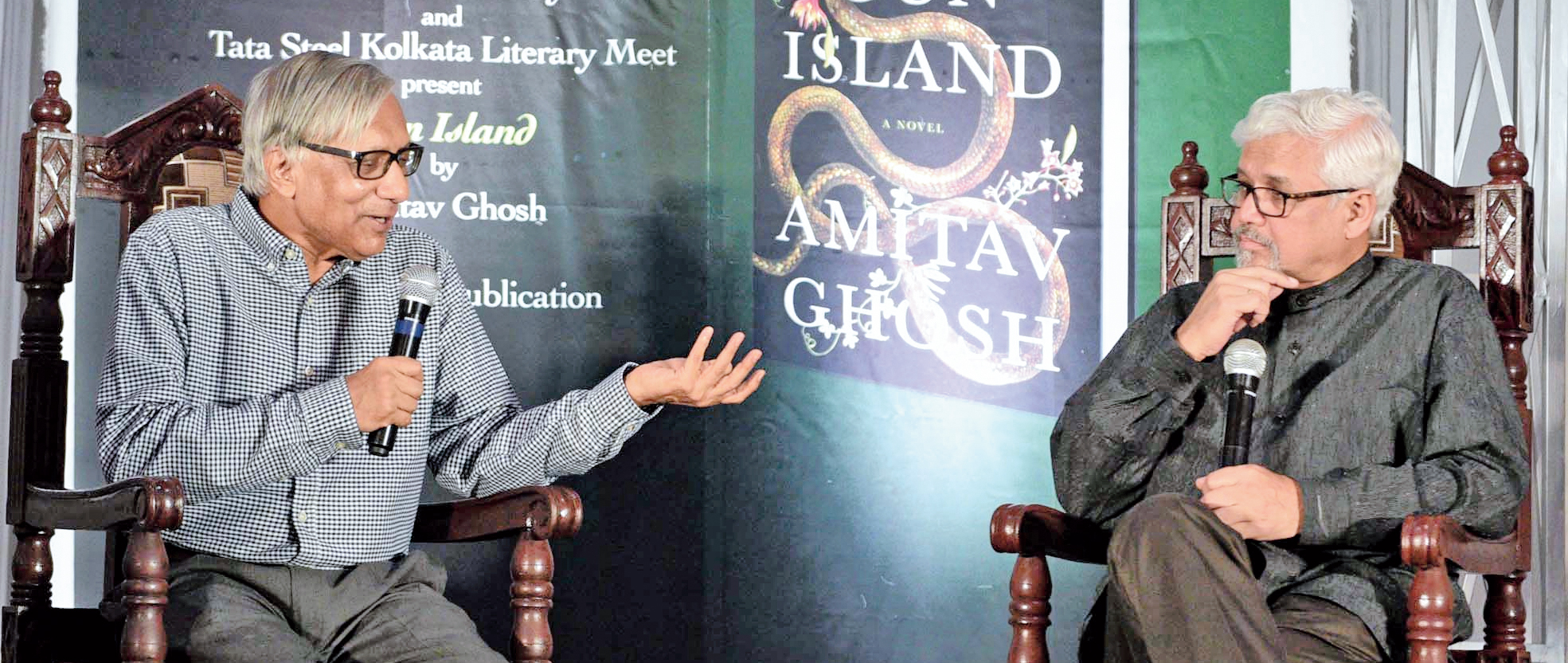

The occasion was the launch of Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island in Calcutta, presented by National Library and Tata Steel Kolkata Literary Meet, and the author was in conversation with Sukanta Chaudhuri, emeritus professor of Jadavpur University, at Belvedere House on Friday.

If Ghosh was returning to a building where he wrote his first article — “It was on etymology which no one was interested in publishing” — his latest release takes him back to the Sunderbans and his 2004 novel The Hungry Tide.

Gun Island shares location and some of the characters with The Hungry Tide, but tackles the story 15 years further downstream. Tipu, Fokir’s son, who was then six, is aged about 20 here.

“When I got back to the Sunderbans it was inevitable that these characters return. In 2000, when I started working on the Sunderbans, it was clear that the area was very adversely affected by climate change — sea level rise, salt water intrusion.... Things accelerated after Cyclone Aila in 2009 and many people had to leave.”

Chaudhuri said that while things happening in the Sunderbans were earlier a trope for the degenerating ecosystem of the world, in the new book the same process is shown to be at work in a more complicated way across the globe.

One such place is Venice, described by Chaudhuri as a “city that is sinking” and “an urban Sunderban”.

Ghosh pointed out that the Venetian lagoon looked startlingly like the Sunderbans from the sky. The similarity did not end there. “As I was walking around the streets of Venice, I could hear Bengali. The entire working class there comprises Bengalis — people who make pizzas, sell chestnuts, work in restaurants.... It was striking to see how they had managed to insert themselves into the sinews of this new world. It seemed you could make your way across Italy speaking Bengali!”

The traffic between nations is not confined to the ordered passage through airports with passports, but involves the human turmoil precipitated by climate change.

Ghosh also drew attention to the invasion of technology in our lives which contributed to the migration. “The most profound effect is disruption of local ties. A boy in a village — be he Bengali, African, Arabic or Pakistani — has access to Internet and social media through which images of life elsewhere flash before his eyes, planting a fantasy in his head. On the other hand, his land itself is collapsing, getting saturated with salt. Of course, poverty creates a reason for escape but not all of it is rational.”

Once they migrate, they want to earn some money and go home. But there is no pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. They lead terrible lives, as terrible in California or Venice as in the Sunderbans.

Yet they cannot return as their families had staked everything to pay for their passage and they would be deemed a failure if they did. “So there is a sense of shame and entrapment. The result is a sundering of ties with family, community and land. It’s a part of the vast destabilisation that we are seeing everywhere,” Ghosh said.