Rahman Ali, 29, is a social media addict like many of his age.

A picture of an old friend he chanced upon on Facebook recently has got him thinking. The friend, Kapil Sheikh, had uploaded a picture of himself in a Border Guard Bangladesh uniform. A question is now playing on Rahman’s mind: What if his family had not opted for Indian citizenship in 2015?

“I am happy for my friend Kapil as he has got a government job. But I am also thinking that had I returned to Bangladesh, I could have also applied for a government job,” said Rahman, a resident of Poaturuthi, an erstwhile Bangladeshi enclave at Dinhata in Bengal’s Cooch Behar district.

Rahman and his family are among 14,856 dwellers of 51 Bangladeshi enclaves — landlocked villages embedded in Indian territory — who opted for Indian citizenship after the governments of Narendra Modi and Sheikh Hasina signed the historic Land Boundary Agreement in June 2015.

Following the signing of the treaty, a 60-year-old problem was resolved. The Bangladeshi enclaves in India became part of the Indian mainland and 111 Indian enclaves in Bangladesh became part of Bangladesh.

For over 53,000 people who did not hold citizenship of any country, the pact marked the beginning of a journey away from no-man’s land.

But citizenship alone couldn’t solve all their woes. “A proper life means livelihood,” said Rahman, an unemployed youth who holds a master’s degree in political science and has studied in Cooch Behar. He earns a living by giving tuition to students.

Rahman’s educational qualification would have been enough for him to apply for the job Kapil has got.

As a BGB jawan, Kapil is earning Tk 15,000 (Rs 12,305) a month. Rahman barely manages Rs 8,000, that too uncertain. Rahman lives with parents and sister and is the sole breadwinner of the family.

Others like Roushan Sarkar, another former enclave dweller in Batrigach, are facing similar problems.

“Several youths from these former enclaves, including two of my brothers, have migrated to other states in search of jobs. We were overjoyed after the Land Boundary Agreement was executed, but the euphoria has started fading because we have to struggle for a livelihood,” said Roushan. His brothers work at a cashew-processing unit in Kerala.

The livelihood options are better for those who chose Bangladeshi citizenship. Not just employment opportunities, the Bangladesh government has also taken up development work in the erstwhile Indian enclaves.

“We are in touch with those who stayed back in Bangladesh. When we hear that the government there has taken up extensive development work in their areas, it only adds to our despair,” said Usman Gani, one of 921 residents of the erstwhile Indian enclaves in Bangladesh who have chosen Indian citizenship and have been temporarily accommodated in camps.

The Telegraph

The Telegraph

In the run-up to the Lok Sabha elections, these residents are getting a chance to air their grievances as politicians are visiting to seek votes.

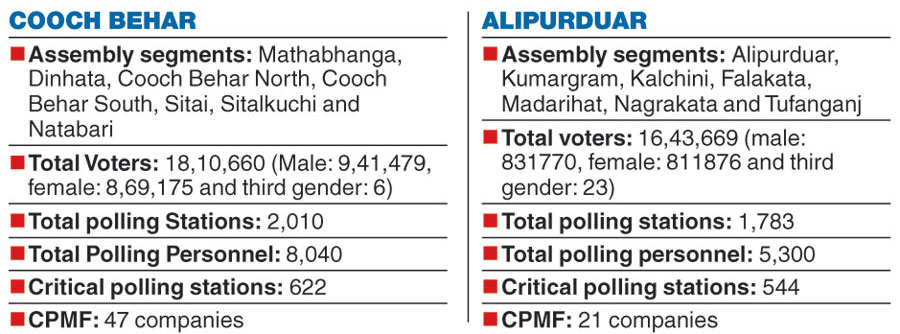

The area comes under the Cooch Behar Lok Sabha seat, which has 18,10,660 voters. The dwellers of the erstwhile enclaves number around 12,000, a small proportion of the electorate in a constituency where the BJP and the Trinamul Congress are locked in a bitter battle.

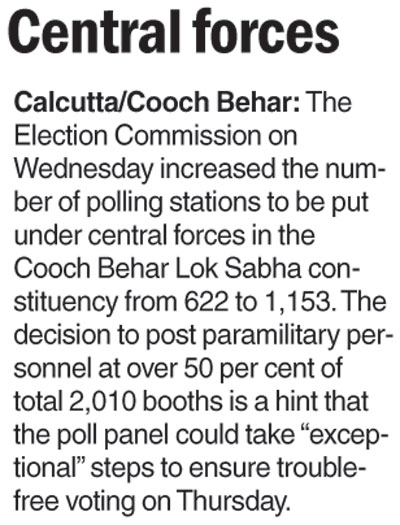

In Cooch Behar, which votes on Thursday, it is a four-cornered contest among Paresh Adhikary of Trinamul, Nisith Pramanik of the BJP, Piya Roychowdhury of the Congress and Gobinda Roy of the Forward Bloc. However, the real battle is between the BJP and Trinamul.

Both the parties have made several promises to the former enclave dwellers.

Rahman and his neighbours said such assurances were not new to them. Ahead of the 2016 Assembly polls, they had been promised infrastructure development in their villages, while those in settlement camps like Gani had been assured of better rehabilitation. But hardly anything has changed.

“The first time, we were new to the election game in India. We had believed the leaders. This time, we are not as gullible. We placed our demands firmly when the leaders came to campaign,” Gani said.

One of the demands is permission to go to Bangladesh to sell their properties.

According to most residents of the area, they have been told by Trinamul leaders that the administration would consider their demand.

“We will see this time…. If our demands are not fulfilled, we will raise our voices again. We have seen bad days in the past and struggled to get citizenship. We are ready to fight it out again,” said Gajen Burman, another resident of the settlement camp in Dinhata.