Even as late as the 1920s, squabbling sisters in households across Bengal were rebuked thus — Gaang-e gaang-e dekha hoy, kintu bon-e bon-e dekha hoy na. Meaning, even rivers meet but not sisters — they are married off early and have to go separate ways. The subtext, therefore, being don’t quarrel so. The olden reprimand remains poignant to date, as much for the memory of siblings wrenched apart in a differently wired society, as for the reminder that once upon a time this geography was river-rich. Bengal, the only state in India that has snowy mountains to its north and the sea to the south, bears a natural slope. This helps hundreds of rivers flow through the land and towards the Bay of Bengal. This also helps develop countless other water bodies.

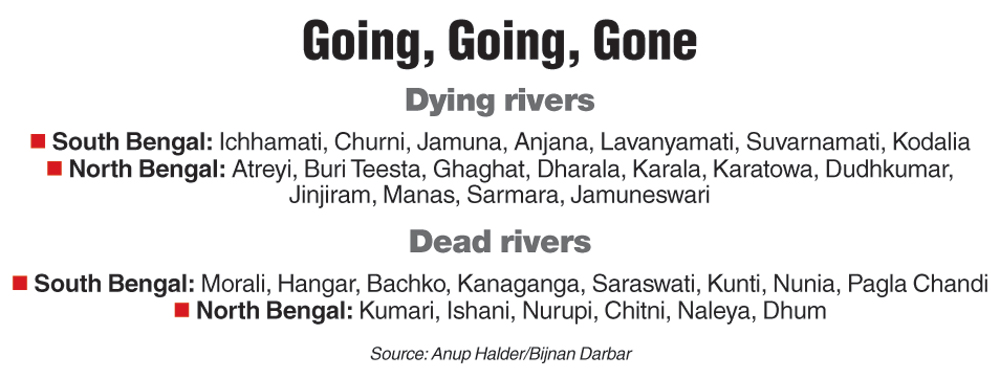

“But in the past 100 years, nearly 700 rivers have died in the delta of the Ganges [in Bengal], and the Padma and the Meghna [in Bangladesh],” says Anup Halder, a researcher on the rivers and other water bodies of Bengal. He adds, “In Bengal, we have lost most tributaries and distributaries flowing eastwards of river Hooghly. Even those that are alive are on the verge of death because of human intervention.”

Historical and geographical factors do play a role in the degradation of rivers, but man-made factors play a greater role. The districts of Nadia and North 24-Parganas in Bengal have already lost a large number of rivers in the past few decades. Environmental activist Swapan Bhowmick and I decide to visit other rivers in that geography that are dying.

Pabakhali village is in Nadia, 80 kilometres north of Calcutta. This is where the mighty Mathabhanga, a distributary of the Padma, bifurcates into the Churni and the Ichhamati. Legend has it that such was the force of the Mathabhanga once that its head (matha) split (bhanga) into two.

Dead — Morali: Local folk talk of crocodile sightings in this river till the late 1950s. Now roads, entire villages and even paddy fields have come up on the river bed Picture by Anup Halder/Bijnan Darbar

Today, from our vantage spot in Pabakhali — the spot where the three rivers come to a knot — it is difficult to imagine such tumble and rush. The place is knitted over with water hyacinth, interspersed with jute and alocasia cultivated by local farmers.

The Ichhamati is a trans-boundary river — one that crosses at least one political border. Bhowmick and I start walking along the river bank. The river source at Pabakhali has dried up due to excessive silt deposits, something that was triggered when the British built a “guard wall” here in 1942. The idea was to tame the river so they could build a bridge over it. The wall broke the force of the waters and rich alluvial silt was deposited on the riverbed. In the days that followed, the dry but fertile riverbed began to attract encroachers and even farmers. Ironically enough, today, farmers must extract irrigation water from the river bed using shallow pumps.

Jyotirmay Saraswati, a social worker and an activist of the Save Ichhamati Movement, joins me. He talks about “mindless encroachments”. He says, “Not just farmland, you will find even roads, markets and temples on the riverbed. In the last 50 years, the average width of the river has come down from 330 feet to 30 feet.”

Saraswati believes the river can be saved if all encroachments are removed and the boundary (of the river) is demarcated. Local people allege that these encroachments are happening with the tacit support of political parties and the administration.

Activists have appealed for excavation of the riverbed and broadening of the width of the river in order to restore its old glory. Saraswati points out that too many concrete bridges with pillars dug into the riverbed have also damaged natural flow.

Saraswati and I keep moving. Close to Narayanpur, 33 kilometres from Pabakhali, I notice an odd construction work. I am told that would be the beginnings of a temple — so what if it juts onto the riverbed?

About two kilometres away, at Kalopara, we stop for tea. A gaggle of fishermen is playing cards and chatting under a banyan tree. Manmatha Mondal, 78, is particularly chatty. He says, “When I tell young people how we would regularly haul giant fish out of these very waters, they are more disbelieving than incredulous.” According to him, several species of fish such as rayek, bheda and baush have completely disappeared, as have the mechho kumir (fish-eating crocodile), dolphins and turtles.

“The river kept getting narrower and narrower. The jungles on the river banks were also cleared. Several species of birds disappeared,” says Saraswati. Mondal recalls a bird called kullo — similar to the eagle — that would be sighted feeding on river fish. He says, “As children we used to recite the rhyme: Kothay neel, Kothay cheel, Kothay kullor basha...” Kothay means whither or where in Bengali.

Vanished — Surodhani: It once sprung off the Hooghly. But on its course now stand paddy fields and the Santipur Bypass. The only wet patch is a squiggle called Surodhani Beel Picture by Anup Halder/Bijnan darbar

In the 1945 Bengali novel, Ichhamati, Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay described this river as “proof of divine artistry, with its banks so verdant, so irresistible to the birds.”

Kothay se Ichhamati? Whither that Ichhamati?

We pick our way downstream along the Mathabhanga — there is no way of telling anymore but I was told as much by Bhowmick. Here is where we make the acquaintance of Basudeb Haldar, a fisherman waiting for a catch. It is 12 noon and he has been waiting since early in the morning. There is not enough fish in the waters.

Earnings from fishing have gone down drastically. Even families that have been doing this for generations have given up the net. They have turned into daily wage labourers instead. Haldar rears a herd of goats to supplement his income. We visit his home, a mud hut. Some fishing nets are strewn carelessly about the place. According to Bhowmick, 30,000 fishermen across 130 villages have been rendered jobless.

Pradip Chatterjee, president of Dakshinbanga Matsyajibi Forum (a forum of the fisherfolk of southern Bengal), says, “We are the biggest losers as rivers die or deteriorate. The right to fish is a basic right for millions of us.” The forum has been fighting for an effective national water policy that will acknowledge fisherfolk as custodians of the rivers. He adds, “Just like indigenous people have land rights we must have water rights. We, the fisherfolk, can save the rivers for our own survival. And also, for the greater common good.”

It is funny that Chatterjee should bring up the greater good, especially because from the sound of it, there is a lot of no-good at play here endangering river life as well as the rivers. Fisherman-turned-labourer Swapan Roy says there is an illegal fish trapping system called badhal that fish merchants resort to in these parts. The badhal uses bamboo poles and specially designed nets to trap river bodies, in the process obstructing the natural flow of water. Roy says, “The system deprives other fishermen of their legitimate catch and damages the biodiversity of the river.”

Farmers and fishermen living by the river are also adversely impacted by effluents dumped upstream by a sugar mill in Bangladesh. “Effluents kill aquatic life,” says Bhowmick. The affected people have now come together to form a river rescue committee. The committee has appealed to chief minister Mamata Banerjee and the prime ministers of India and Bangladesh to save the river system. “Despite appeals to both the state and the Centre, the simple solution — a waste treatment plant in Bangladesh — has not materialised,” says Bhowmick, the committee secretary. But, he adds, the protests have been successful in checking illegal fishing and efforts are on to stop municipal bodies from dumping waste into rivers. He continues, “Following our petition, the municipal corporation of Ranaghat has been directed by the National Green Tribunal [the all-India forum for redressal of environmental problems] to establish sewage treatment plants and take steps to revive the river that joins the Hooghly at Chakdah.

While the Ichhamati and Churni are both on the verge of death, Halder lists other rivers that have simply vanished or are on the verge of it. The Jamuna tops the list of stolen rivers; all that is left of it are bits and pieces of water bodies in the Kalyani-Haringhata area. It is very difficult to trace the original riverbed that remains lost in a warren of markets, apartments, schools, temples and mosques.

He shows me photographs of paddy fields from villages in interior Bengal that used to be tributaries of the Jamuna, or streams, even half a century ago. Chaiti, Jhora, Lavanyamati, Suvarnamati, Sonai, Morali, Anjana and Surodhani are some of the lost rivers. In the case of Morali, says Halder, there is no trace of the river; it is all dirt-track and paddy fields. He blames indiscriminate extraction of water — for drinking and irrigation — and dumping of wastes and mining of sand and clay for this.

According to Halder, the reckless extraction of water damages the aquifers (an underground layer of water-bearing permeable rock), mobilises minerals deposited deep inside the earth, basically leading to contamination of drinking water with arsenic, fluorides, chlorides and other harmful chemicals.

Bijnan Darbar is one of many non-government organisations campaigning against these practices and for the resuscitation of rivers. After much protest by villagers and different environmental groups, the Bengal government allocated Rs 26 crore for excavation of the Jamuna. This was in 2018.

It is already dusk by the time we reach Duttapulia, 30 kilometres from Pabakhali. This bit of the Ichhamati now serves as a sewer, thick with waste from the market — styrofoam boxes used to store fish, rotting vegetables and fruits. Says Saraswati, “The pile of garbage often catches fire; then it is literally a river on fire.”

Quintessential Ichhamati — lost but lyrical to the end.