April 19: When Adam Szymczyk, the director of Kunsthalle Basel and artistic director of Documenta 14 in 2017 in Kassel, was in Calcutta in 2014, he said he was much impressed by the "distinctive" work of Ganesh Haloi, which, he asserted, was "difficult to box it using the categories we have".

He was obviously taken in by Haloi's "book" based on the copies he made in Ajanta of the murals when he was employed by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in 1957. It is a shame it has not found a publisher yet.

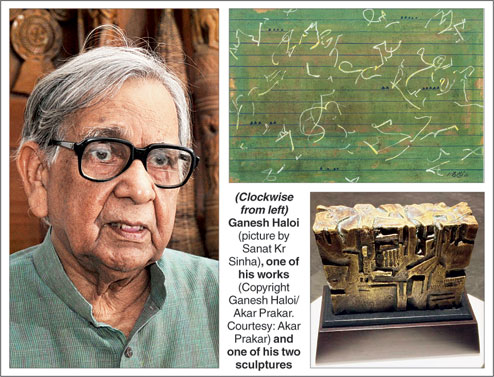

Sure enough, two sets of Haloi's works are being exhibited at Documenta 14 - in Athens from April 10 to July 16, and in Kassel from June 19 to September 17. Two of Haloi's sculptures are also included. This is a rare honour for an Indian artist, but on Monday, when this correspondent met Haloi in his modest home, which houses his studio and his vast collection of folk art and books on art, he remained composed. He seemed withdrawn.

"When people appreciate my work I feel it is worthwhile," he says with a wan smile. But later he talks enthusiastically about his childhood in former East Bengal, where he was born in 1936, and the hardship he bore to become an artist.

Although his contemplative and serene paintings betray no trace of it, Haloi had said in an earlier interview that one does not feel pain any longer when the pain has reached a certain intensity, and one does not feel the pangs of hunger either after being deprived of food for a long period of time. He has arrived through sheer willpower.

His latest works exhibited in January at Akar Prakar were chosen for Documenta 14. As in his earlier works, in these, too, nature - the lush paddy fields uniformly divided into rectangles that are watered by the bounteous rivers of Bengal - was the stimulus. But he does not have any particular riverine land in mind when he takes up his brush. What viewers observe in his gouaches is the projection of his contemplations on the greenery that surrounded his childhood home at Jamalpur in Mymensinh district of what is now Bangladesh and elsewhere.

The farmland was irrigated by the river and huge water bodies known as "hawar", and this accounts for his strong bonds with nature and water that is reflected in his work. From childhood he had been interested in drawing, and he made copies of pictures in books and calendars.

Then the country was splintered and he and his family left their home behind in 1950. He was only 15, and his family had to seek shelter in a refugee camp. Initially, they stayed at Cooper's Camp near Rangahat, and thereafter, the refugees were relegated to neighbouring states.

Haloi along with his family was sent to Rajmahal in Malda and thereafter, Mokama in Bihar. His touch was unsure, but he used to sketch the village and its surroundings. The 15-year-old boy came alone to Calcutta and joined the Government College of Art & Craft. Abanindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose were his two ideals.

His elder brother had given him some cash to get himself admitted in 1951, plus he received a refugee stipend. He used to walk to the college from Burrabazar where he lived. At Munger, which he visited during holidays, and in Calcutta, he sketched whatever caught his eye.

In 1955, Haloi went for an excursion with his classmates to Kathmandu where he spent time sketching the picturesque town and its people. But he fell ill as he had no warm clothes, and was sent back. After passing out of college, he along with some other artists were recruited by the ASI to document the Ajanta frescoes for the National Museum in Delhi. So off to Ajanta in 1957 where he worked till 1963. Recalling his first reaction on witnessing the magnificence of the frescoes, Haloi says: "I hung my head before its splendour and enormous scale."

He drew the Marathi women working in the fields of Ajanta village. He says he observed a maulvi carrying a lantern and a stick, and soon the same man appeared in a painting wearing dark clothes with the grey shadow of a mosque behind him, Abanindranath style.

Haloi recalls an exhibition of British sculpture in 1968 that made a tremendous impact on his thinking. His earlier paintings of rock formations and stratification showed the influence of cubism. Haloi visited the West quite late in life, but he kept track of the art movements through the numerous books that he picked up.

However, his favourite authors are Tagore, Bibhutibhushan, Manik Bandyopadhyay, and he admires Abanindranath's Bageshwari lectures on art as well. It is easy to pigeonhole his art as "abstraction", but Haloi's paintings defy classification. Adam Szymczyk had described the contemporary as "a moment of transgression", and this non-conformist element he had perhaps discovered in Haloi, the first Indian artist outside the great Baroda coterie to be chosen for Documenta.

Haloi's paintings are akin to the poems of Jibanananda Das and their evocation of the verdant land of Bengal and sparkling water bodies. The layouts of Haloi's kaleidoscopic paintings are as perfect as checkerboards, and the colours are harmonious as in a musical composition. The artist loves Western classical music.

Much earlier, he had done some pen-and-ink drawings that are unmistakably cubist compositions. However, in his later paintings, Haloi's compositions of angular forms with multiple planes are perhaps closest to Gaganendranath.

As far back as 1975, he had done an oil painting of crocodile hunting in Brahmaputra river, where the emphasis is on dividing space with colour - large splashes of vermilion on ochre with a tinge of green. In a watercolour that has the delicacy of Chinese paintings, he depicted hyacinths in a pond in which fish dart about.

Haloi's vision is symbolic, and human presence is indicated through elements such as the suggestion of temples, the stubble in desolate paddy fields and boats with colourful pennants flirting with the breeze.

His current paintings are enriched by a touch of whimsy - the jagged lines, enigmatic squiggles and hieroglyphs recall musical notes. His paintings have the rigour of architectural drawings. Yet, within that restricted space, they are open to improvisation like musical compositions.

Haloi says: "The firmness of geometry is inherent in my thinking process. It is as strong as life itself. It is never limp. In my paintings one can observe the struggle to try and know oneself. You never know where you will end up. But you are electrified - the kind of exhilaration one feels on viewing a lofty mountain."