Soon after Harendra Coomar Mookerjee was sworn in as the governor of West Bengal in November 1951, he expressed his desire to hold a seven-a-side football tournament for under-14s with all schools and clubs being eligible. The incentive was colossal. A shield was to be presented by him to the winners and the final would be played on a specially prepared ground within the premises of Governor’s House.

One afternoon during the next summer holiday of our school, my uncle asked all of us, his nephews aged between 10 and 14 years, to get ready to attend the final of a football tournament. One finalist had to be Ballygunge Institute, a fledgling club near Gariahat Market of which he was the chief patron, whose claim to fame was a boxing ring planted in the middle of a small plot of land between rows of houses. Their opponent, we soon found, was a team of smartly turned out boys from a local school.

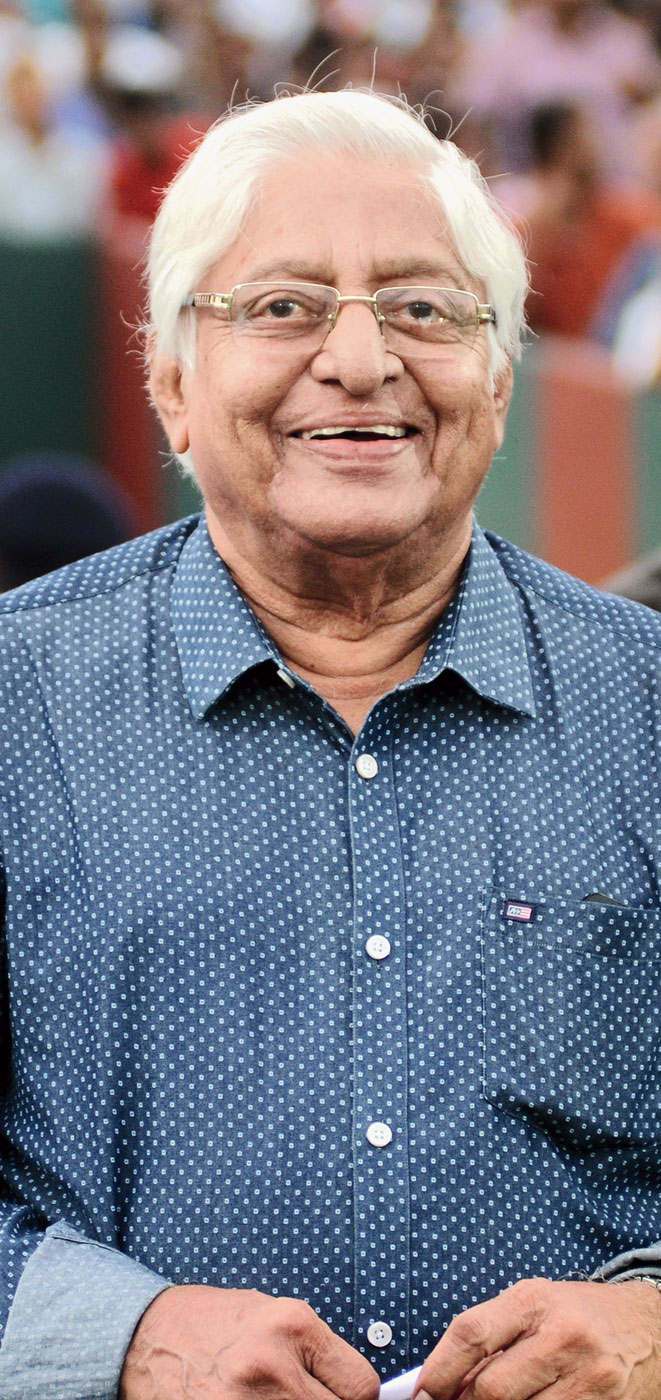

“Chuni is our trump card,” my uncle said pointing to a gangling, skin-and- bones youngster.

The first five minutes of the match were unimpressive. There were lots of fouls and misdirected passes by both teams. Then it was as if Chuni decided that the governor deserved better. He collected the ball from his goal-keeper, dribbled past everyone who came in his way and pushed it into an empty net.

By the time the match was over, he had done it seven times out of the nine goals his team scored. During the second half, with the opposing team trying to foul him to put a stop to this carnage, he would nutmeg the centre-half and go round him to collect the ball, much to the spectators’ delight.

There was no doubt in our minds that a star was born that sultry afternoon.