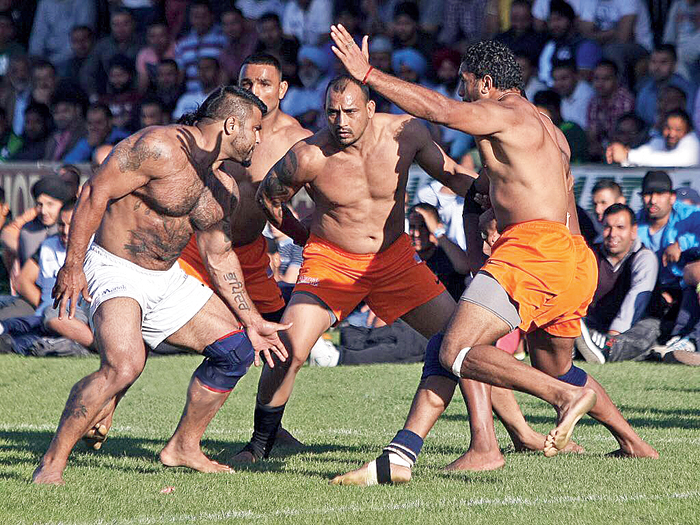

Raid. Tackle. Slither. Tumble. Male bodies lunge at one another. Thick legs, several pairs, seemingly conjoined, dance like a giant spider on court — sometimes this way, sometimes that way. Then they start to close in on the Other. In. In. In. An advertisement banner for hair oil peeps in from behind a tangled web of sweaty thighs. (Thigh five it seems has replaced the high five as the trendiest form of salutation.) The league’s official Twitter handle pulsates with the hashtag #IsseToughKuchNahi. The commentator’s voice is a hypnotic drone. (Selective ‘rs’ rolled and spun expertly for effect, like hot chapatis on a flat chulha.) Listen up, he is saying: “…he lurrres the right cover defender towards him and then with rrraw powerrr drrrags him down the middle… Maninder gets rrrid of Sandeep… Prapanjan now it is. Aaaand… DOOOBKI. DOOOBKI. DOOOOOOBKIIII from Prrrapanjan.” And just like that Season 7 of the Pro Kabaddi League or PKL is upon us — the first season was in 2014. Bulls versus warriors, steelers versus giants, pirates versus paltans. Twelve teams from different parts of India clashing with each other since July 20 right through to October. Playing in Patna and Panchkula, Mumbai and Chennai, Calcutta and Ahmedabad, among other locations. Supported in every which way by more than a dozen sponsors. Each team eyeing a prize kitty that is sure to exceed the last two seasons’ 8 crore rupees. Yes. Kabaddi. Kabaddi. Kabaddi. Kabaddi… Humble, kabaddi, kabaddi, kabaddi, kabaddi.

In his 2018 book Kabaddi By Nature, British sports journalist Vivek Chaudhary raises the question — does the rise of PKL say something bigger about where India is at the moment? Chaudhary, however, is careful not to read too much into the phenomenon or, as he says, using it to interpret bigger issues. What he does is present a variety of vested voices he recorded during the four years the book was in the making. One such is STAR’s Sanjay Gupta (STAR is the official host and co-promoter of PKL) who says: “My generation always looked at things abroad and thought they were better… But there’s a new generation that is prouder to be Indian.”

True, false, debatable, Gupta’s comment is applicable only to Indians in India. As I gather from the book and my telephone conversation with Chaudhary, the Indian diaspora has always been kabaddi proud. Of course, Indian in this context equals the Punjabi diaspora. He writes, “Southall is the unofficial capital of the UK’s Indian community and the spiritual home to diasporic kabaddi.”

Chaudhary tells me how he discovered during his travels to India that beyond Punjab everyone was shocked to hear that kabaddi is integral to the Punjabi diaspora in the United Kingdom. He says, “Now, after the UK, the biggest tournaments are in Canada. Kabaddi is also played in Italy and France, though not too many in India are aware.”

The emergence of kabaddi in the UK in the early 1960s was driven by the gurdwaras in response to the arriving Punjabis, among whom was Chaudhary’s father. A gurdwara in Southall — Gurdwara Singh Sabha — formed one of the first kabaddi teams; it also organised the UK’s first kabaddi tournament in 1969. Says Chaudhary, “Kabaddi is something I was brought up with. My father would take me along to matches and tournaments. One of the things that is repeated often at kabaddi tournaments in the UK is that this isn’t just a sport for us. It is part of our culture, a connection to our mother country, a celebration of our rural background. ‘Poonjabis’ and kabaddi are entwined.”

He zooms into the UK kabaddi scene as it is now. Most clubs still carry the name of the gurdwaras but the responsibility of organising teams and funding them has passed on to local business families. There are 12 teams representing a city each, cities with Punjabi dominance such as Birmingham, Leicester, Slough, Berkshire. Over the course of three-month seasons, they travel around. Chaudhary puts out the idiosyncrasies of the sport as it is in the UK. (To be read with the writer’s wry-indulgent humour.) Format of the game: different from the standard style. The Punjabi or circle style is supposedly a more confrontational, combative version. Matches are “raw, boisterous, chaotic”. A 45-minute affair with a five-minute break often takes 90 minutes to complete owing to constant interruptions. Describes Chaudhary, “…enthusiastic fans running onto the field to hand shagan (the ceremonial prize money) to players who have just completed a successful raid or foiled one.” He continues, “Matches often start late… Sometimes they do not start at all. Often, the location of the tournament is only revealed at the last minute… To play kabaddi you need strength, speed, guile, but to follow it you need incredible amounts of patience…”

He introduces individual players. Sandeep Singh of Wolverhampton. Born in Punjab. Captain. Stopper. Famous for his ‘kainchi’ move. Has earned the sobriquet of Gladiator of the Black Country — a reference to the polluted iron foundry city in the British midlands that is his home now. And Slough’s secret weapons — Pakistani raiders Mohammad Chisty aka Electric and Lala Ubaid Abdullah nicknamed Jet. He also writes about the players’ dietary predilections, and the fandom of the pinni — a sweet made of sugar, cream, wheat and ghee, which he calls a “cholesterol gobstopper”. Players, he notes, consume a dozen pinnis each day, half a kilo of porridge in winter, five eggs, two kilos of milk and four aloo parathas. And a repeat of all of it for dinner. “No doubt the high-tech food gurus of the PKL clubs would have something to say on the matter but this world of kabaddi exists in the Stone Age compared to the one on protein shakes and vitamin supplements that is broadcast on Star Sports,” Chaudhary writes.

@KabbadiWorldwide, Facebook page of Kabaddi UK

Nearly a quarter of the UK’s kabaddi players are from Pakistan, the rest from India, and a handful are Britons of Indian origin. According to Chaudhary, kabaddi fans in the UK are not a partisan lot; everyone appreciates good play and jappha — the term for the moment when a stopper pins down a raider. In the chapter “Punjabis and Pinnis”, he writes, “In the world of British kabaddi at least, Punjab remains united. Around the circle of a kabaddi match culture subsumes politics.”

Outside of India today, kabaddi might subsume geo-political differences, but pre 1947 it represented the body politic prepping for the freedom struggle. A good portion of Chaudhary’s book is about the Hanuman Vyayam Prasarak Mandal or HVPM, a sports club in Maharashtra’s Amravati, founded in 1914 to “uplift the traditional system of exercise and sports and instil in youths the spirit of the national freedom movement”.

Chaudhary tells me he had read about the HVPM in passing, how it had sent a group to Berlin in 1936 at the time of the Olympic Games. While writing the kabaddi book, he got in touch with the present-day authorities there and was surprised when he was welcomed to dig into a well-maintained and rich archive.

The form of Kabaddi By Nature facilitates time travel — one can enter it from any chapter, self-contained and concise. In one such, borne on his archival finds, Chaudhary writes about the two dozen Indians from HVPM who went to Germany in 1936 and floored Adolf Hitler and the Berlin Olympic Committee with their kabaddi moves. “Does your team represent the average Indian?” Hitler had asked. To this day, Amravati remembers those Games as the “Hitler Kabaddi Games”. Chaudhary for his part makes the square point that the HVPM members were not Nazi sympathisers, but they had undertaken the trip to showcase India’s freedom aspirations through her indigenous sports. To them Hitler’s words meant something.

Says Chaudhury, “It was during my work in the HVPM archives that the wider story came out, about this club’s role in the freedom movement. It was fascinating. Club members had actually gone to Japan; they were among the forerunners of the Indian National Army. They had been in contact with Subhas Chandra Bose…” When he returned to London, Chaudhary looked up some of the names and references in the British Archives. He went to the British Library and started to go through the India Office files. “It turned out a lot of these guys from the HVPM were actually under the surveillance of the British Intelligence for their reactionary ways,” he says.

Names and exploits tumble out. Specifics of who met whom, achieved what or not in the freedom struggle. The revolutionary, Raj Guru, was also a member of the HVPM. But what is more surprising is how much of this has fallen off history’s radar. Somewhere along the way, with the emergence of the English-speaking urban elite as the influencers of Independent India, the country moved in a different direction. Away from kabaddi and its ilk, practically plastered with cricket. Forget being celebrated, the stories of the significant contributions of the HVPMs from India’s small towns died out of the mainstream narrative.

“It is sad,” says Chaudhary.

Cut to 2019. Siddharth Desai. Rs 1.45 crore. Telugu Titans. Nitin Tomar. Rs 1.2 crore. Puneri Paltan. Rahul Chaudhari. Rs 94 lakh. Tamil Thalaivas, Monu Goyat. Rs 93 lakh. UP Yoddha… Those would be the figures from the PKL 2019 players’ auction. Prior to PKL, top prizes at kabaddi tournaments ranged from Rs 20,000 to Rs 50,000 and all that players ever wanted was the financial security yielded by a government job to keep playing. (Goyat is a havildar in the army and Tomar in the navy.) Parallely, there is the NRI factor at work. In Punjab, the Shera Punjab Academy California advertises in the local dailies to select kabaddi trainees. Hundreds of boys turn up at the trials. Pros are signed up by kabaddi clubs in England and Canada. Tournaments in the state are funded by NRI organisers. Chaudhary writes, “Last year, a businessman from Canada bought a Mercedes… for the captain of his winning team.” It might sound as if it is about the money only, but the intangibles are possibly more. Chaudhary calls them the “human benefits”.