It’s funny to recall now, but in the years preceding his maiden major title at the 2008 Australian Open, when Novak Djokovic was an up-and-coming whippersnapper, one of the first aspects of his personality that penetrated the public consciousness was his penchant for performing amusing impersonations of his contemporaries: Rafael Nadal, Maria Sharapova, Andy Roddick. A couple of headline writers, riffing on his jocular antics and apparent heirdom, anointed him the “clown prince” of the sport. Fourteen years and 20 grand-slam titles later, Djokovic has come full circle. The clown prince is now the fool king-in-exile.

Djokovic, the world No 1 and possibly the greatest male player in the history of tennis, is fighting to avoid deportation from Australia and disbarment from the tournament that may consecrate his greatness. He stands on the brink of ultimacy; he stands in the pillory of ridicule. If his appeal succeeds and he is allowed to compete at the Australian Open, he may well win a historic 21st major. But whatever happens, he also seems like a diminished figure, one whose legacy is now irrevocably corroded.

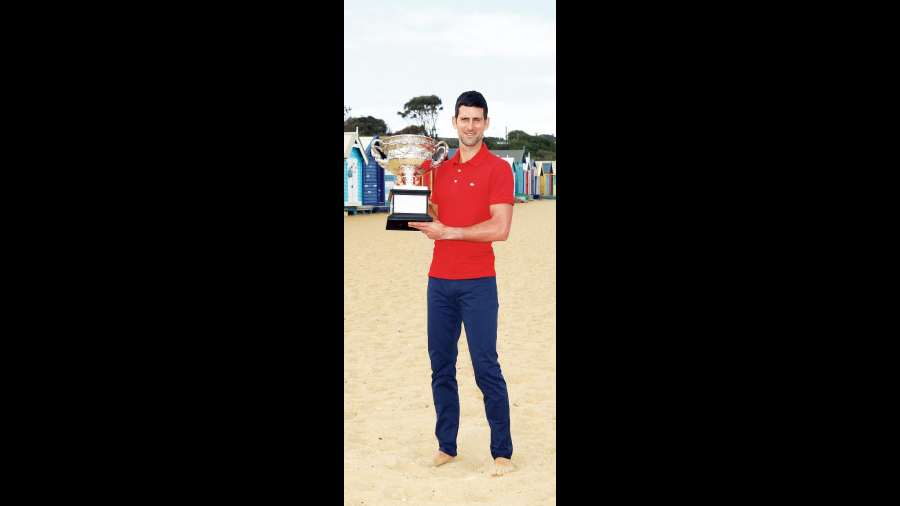

Djokovic has spent the past year accelerating towards an apotheosis. Catching Roger Federer and Nadal’s total of grand-slam titles has been the epic quest of his career. At first it seemed impossible; slowly, it has come to seem inevitable. He has won three of the past four grand-slam tournaments, and at Wimbledon hauled himself level with his great rivals. Even at the one he didn’t win, the US Open, the crowd which had been against him for almost his entire career seemed to recognise the greatness of the dauntless, dogged antihero. By winning in Melbourne, where he has been absurdly dominant, triumphing on nine occasions, he would move into clear air, and crown one of most Herculean sporting feats of all.

Yet Djokovic has also been demonstrating a reckless disregard for science and a quickening descent into downright dangerousness. He has used his social media to platform quacks and his book to promote junk science. At the height of the pandemic, he organised an exhibition tournament that eschewed social distancing and infected several players, their wives and coaches. He flew into Australia, a nation that has endured soul-sapping lockdowns and privations in the spirit of collective sacrifice, blithely trumpeting a vaccine exemption, igniting an international diplomatic incident and exposing himself to fury, scorn and derision.

You know that moment in a Djokovic rally where his opponent hits a flat, wrong-footing shot into the corner, and as Djokovic changes direction, it seems for a split-second like half the atoms in his body are moving one way and half are moving in the opposite direction? It feels like we are watching the real-life version of that.

The strange thing about Djokovic, who at this precise moment may be the most divisive person in the world, is that he has never wanted to polarise. On the contrary, he has always seemed to crave, perhaps a little too transparently for some people’s liking, the unanimity that Federer and Nadal inspire. He is a child of division, who grew up in Belgrade amid the Balkan conflict, and in his self-positioning comes across as someone who wants to please, to unify, to bring people together.

Many of his public utterances, delivered faultlessly in the five languages he speaks, are couched in folksy generalities: the human race, the whole world, the vibrations of the planet — that kind of thing. When in Wimbledon, he likes to visit the local Buddhist temple; when in Melbourne, he communes with a Brazilian fig tree in the botanic gardens. This is the face that Djokovic wants the world to see: the global citizen, the all-embracer, the universalist.

But Djokovic has been unable to resist being pulled into the rip tides of the culture wars. He was unfortunate, I think, to be castigated for some fairly benign comments on dealing with pressure after Naomi Osaka’s withdrawal from the French Open, having in fact reached out privately to her to offer his support. Other positions have been murkier though. Enthusiastically calling Alexander Zverev a “great guy” despite the allegations of domestic abuse against him. And now, of course, topping it all, his anti-vax stance.

It’s possible to have sympathy for Djokovic. Personally — and I know this is a minority position — I have always instinctively quite liked him. He has had his share of stroppy outbursts on the court — a charge that could equally be levelled at Federer, Andy Murray and Serena Williams — but overall he has been a respectful and gracious champion, humble in victory and defeat, and has dealt with the existential purgatory of playing in front of crowds that are almost always willing him to lose with as much magnanimity as any of us could hope to muster.

It was hard not to be moved by what unfolded at the US Open final in September, where Djokovic wept because he finally felt the warmth of a crowd’s affection at his back. The tragedy of his situation is that, in a parallel universe, that might have been the start of an Indian summer in his often antagonistic relationship with the tennis public. It’s not hard to imagine a world where he went to Melbourne Park — the place where he has always had most affinity with the crowd — won his tenth title, and was cheered to the rafters in a moment of catharsis and deliverance, finally the greatest, loved at last.

Whatever happens from here, it surely won’t be that. That is a fact for which Djokovic has only himself to blame. Beyond this month, the future looks even more uncertain. If he’s not prepared to get vaccinated to play in Melbourne, what are his prospects of competing at Roland Garros? Might he be so upset by his vilification that he quits altogether? Could he end up stuck on 20 majors, perhaps eternally bound together with his two great rivals?

For so long it has felt inevitable that Djokovic would overtake them, in part because of his supernatural ability to defy the laws that impinge on other athletes: the elastic limits of the human body, the constricting effect of pressure, the slow creep of time. Now we wait to see if his defiance of more prosaic rules will finally ground his odyssey for good.

Dijana Djokovic (banner in hand), the player’s mother, and Srdan Djokovic (in red cap), his father, attend a rally in front of Serbia’s National Assembly as World No.1 tennis player Novak Djokovic fights deportation from Australia after his visa was cancelled.