Get up, stand up, stand up for your rights!

Get up, stand up, stand up for your rights!

Get up, stand up, don’t give up the fight!

The Bob Marley song was about standing up for the rights of Black people. The reggae god wrote it with Peter Tosh, influenced by their childhood struggles in Jamaica, where they had to fight for their Rastafarian religion.

Rastafari originated among the socially deprived Afro-Jamaican communities in the 1930s. Growing up in Kingston, Michael Holding had been largely influenced by its Afro-centric ideology, which was a reaction to the then-dominant British colonial culture. Those principles he has since felt deeply about and empathised with.

During the opening day of the first Test of the England-West Indies series at Southampton recently — players turned out sporting the Black Lives Matter credo which became a global outcry following the streetside murder of George Floyd by policemen in Minneapolis in the US — Holding delivered a four-minute oration on race and discrimination that has been described as his “finest spell” on English soil.

He wept as he recalled his mother’s experience of being disowned by her family for marrying a man they considered “too dark”. The racist overtures he went through during his playing days in England, Australia and South Africa all seemed to flood back to memory. It was a stunning burst of emotion, the hard truths about racism delivered in his trademark silken baritone. Holding, 66, reminded countless sufferers of Muhammad Ali’s famous words — “In your struggle for freedom, justice and equality, I am with you.”

In his autobiography No Holding Back, the Windies legend recounts what he went through during his first tour of England in 1976. “Tony Greig’s ill-judged comments that he would make us ‘grovel’ riled us to the extent that we needed no further motivation. It was a highly insensitive remark to make about a largely Black team. Remember, he was a white South African, qualified for England only via his parents... and it sent out the wrong message, pure and simple. We saw nothing else.”

It stoked their political consciousness. Some of the players, including Holding, wore a wristband in the colours of the Rastafari movement. In the documentary, Fire in Babylon, Vivian Richards explained their thought process: “Green for the land of Africa. Gold for the wealth that was stripped away. Red for

the blood that was shed”.

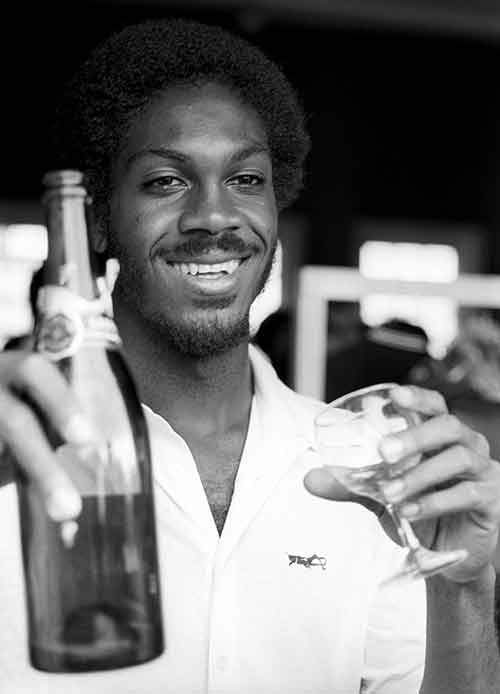

West Indies won the five-match series 3-0. Richards plundered 829 runs in seven innings with two double tons and a highest of 291. Holding had match figures of 14 for 149 at The Oval, which remains the best by a West Indian in a Test match.

The series was also remembered for Holding’s explosive spell to 45-year-old Brian Close during the second innings of the Old Trafford Test. All of Holding’s seven overs to Close were maidens. With no limit on bouncers, he peppered Close repeatedly.

During the final Test, Greig reacted to taunts from West Indian supporters by crawling across The Oval outfield “grovelling”.

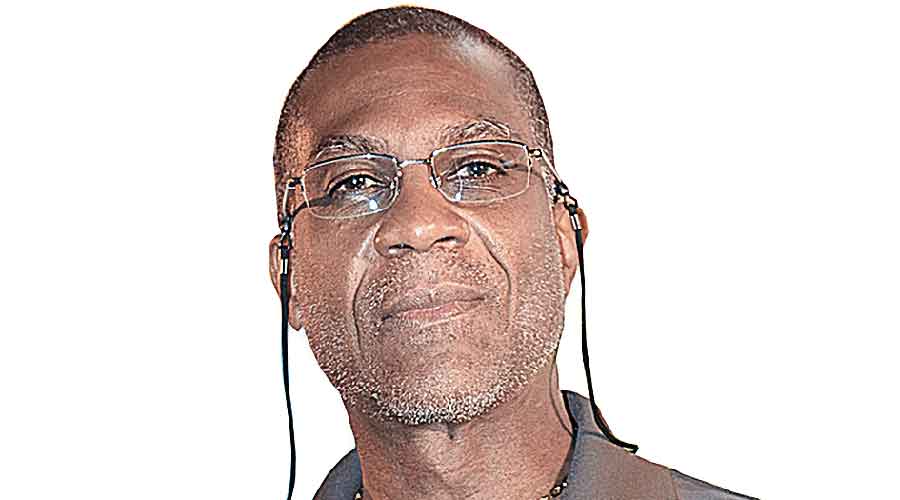

'I don’t think T20 is good for the game. I don’t even call that cricket. It’s Barnum and Bailey circus entertainment' Pic: ESPNCricinfo

Over the years, Holding has earned the reputation of being a straight, even blunt, commentator who takes no pressure and believes in saying it like he feels it. This was best demonstrated during the 2019 World Cup in England when the International Cricket Council (ICC) tried to censor his criticism of umpires on air. This was after he had termed the umpiring in a West Indies-Australia match as “atrocious”. The ICC, in an email to Holding, reminded him of “the importance of maintaining the highest standards and uphold the game’s best values and spirit while covering the tournament”.

In a scathing reply, Holding said: “Commentators are being more and more compromised by controlling organisations to the point of censorship... As a former cricketer, I think cricket should be held to a higher standard. Is the objective to protect the umpires even when they do a bad job? I am sorry, but I am not going to be part of that.”

The ICC didn’t dare to take it further. That wasn’t the only stand-off Holding had had with the ICC. In 2007, despite being a staunch critic, the world body decided to include him in its cricket committee.

The bonhomie didn’t last long; he quit in July 2008 unhappy with the ICC’s decision to change the result of the 2006 Oval Test from a forfeited win for England to a draw. Holding felt Pakistan’s refusal to play should not go unpunished even though they were not guilty of ball-tampering. The forfeiture was later reinstated, but Holding resolved not to rejoin the ICC. Not too long ago, Holding had also made it clear that the BCCI’s inclination to dictate terms to other member boards at all times was detrimental to the game. Says former India opener Anshuman Gaekwad, Holding’s close friend: “Mikey is very down-to-earth. He is touchy about issues he feels deeply about. Those who say fast bowlers don’t have a heart must look at Mikey. He maintains relations and is a very different guy. You can make out how hurt he was by the torture of Black citizens in the US.”

With a run-up that was compared to a Rolls Royce by umpire Dickie Bird, Holding would consistently bowl at 90 miles per hour (nearly 145 kilometres per hour) or more. As a kid, he was a fine athlete, good at long jump and hurdles. He showed no interest in making sport his living, though. He wasn’t a professional cricketer until 1981 and didn’t wish to be one. He had a job as a government computer programmer in Kingston.

He lacked cricketing ambition even when he toured Australia in 1975-76. On that tour, Holding, at 22, displayed discipline and precision that was way beyond his years. West Indies lost the series 1-5, with Holding blaming the “poisonous atmosphere” and Clive Lloyd’s detached captaincy for the defeat.

In 1977, Lloyd approached Holding about joining the World Series Cricket, a World XI led by Greig to play against Australia. The scars over Greig’s 1976 comment were still fresh in memory but Kerry Packer made him and others realise what their skills were actually worth. Besides the fierce competition on the field, players’ earnings improved substantially. Holding was able to buy his first car and later a house from such proceeds.

To Indian fans, Holding remains a villain for having orchestrated a victory at Jamaica’s Sabina Park in April 1976 — a game that has gone down in history as the bloodiest ever.

In his autobiography Sunny Days, Sunil Gavaskar wrote: “To call the crowd a crowd in Kingston is a misnomer. It should be called a mob... The way they shrieked and howled every time Holding bowled was positively horrible. They encouraged him with shouts of ‘Kill him, Maan’, ‘Hit him, Maan’, ‘Knock his head off Mike’... The whole thing was just not cricket.”

India, in their second innings, declared at 97 for 5, only 12 runs ahead. There was no batsman left fit to bat. West Indies won the match by 10 wickets and the series 2-1. “Some of the deliveries were at rocket pace. I remember one such delivery I just couldn’t see. One hit my left ear and the spectacles went flying. Everything went numb and I could only hear a humming sound. I was bleeding profusely,” recounted Gaekwad, who batted for seven-and-a-half hours for his gutsy 81.

But the animosity never spilled beyond the ground. Says Gaekwad, “Mikey remains one of my best friends and we are in constant touch.”

Fast as lightning, smooth as silk, is how Holding has often been described. If Shane Warne is credited with bowling the “ball of the century” to Mike Gatting at Old Trafford in 1993, Holding holds the distinction of “the greatest over in Test history” to Geoff Boycott at the Kensington Oval in Bridgetown, Barbados, in March 1981. The first ball rapped Boycott on the gloves and the subsequent deliveries were quicker. The legendary opener was flinching in the face of pace. The final delivery sent his off-stump flying to the delight of the crowd. “The hateful half-dozen had been orchestrated into one gigantic crescendo,” wrote Frank Keating, the English sports journalist. “Boycott looked round, then as the din assailed his ears, his mouth gaped and he tottered as if he’d seen the Devil himself.”

The most acrimonious Test series Holding was involved in was the 1979-80 tour of New Zealand. It all started in New Zealand’s second innings at Dunedin when a vicious delivery from Holding took John Parker’s gloves on way to wicketkeeper Deryck Murray, but umpire John Hastie turned it down. A furious Holding kicked two stumps out of the ground at the striker’s end. “This was not cricket,” Holding wrote, “and I didn’t have to be part of it. I was on my way to the pavilion, quite prepared not to bowl again, when Clive Lloyd and Murray persuaded me back.”

Bruce Edgar, the former New Zealand opener, though, saw the humorous side of the episode. “It was funny. Parker was in pain. He even removed his gloves! The ball had struck him there. But then, the umpire had given him not out!”

Today, Holding spends most of his time staying between Newmarket, north of London, and Miami in Florida. He is married to Laurie-Ann, from Antigua. Holding has a son Ryan from his first marriage to a Sri Lankan, Cherine.

Having been forced to retire from the sport in 1987 because of back and hamstring injuries, he ran a petrol station for some years in Kingston, called Michael Holding’s Service Centre, resisting the temptation to

go into coaching. He decided to sell the enterprise once he started giving more time to commentary.

He started his broadcast career with Radio Jamaica at the insistence of a producer friend. The transition to TV happened in 1990 at the behest of journalist Tony Cozier in the Caribbean. Since 1991, Holding’s mellifluous Jamaican accent has made him a regular with Sky Sports. He was meant to have retired from the commentary box this year, but the coronavirus pandemic may just have gifted us another year of Holding on the telly.

Holding has always stuck to his beliefs. Despite the lure of big bucks, he has refused commentary offers for the T20 format. Even the IPL has failed to lure him. “I don’t think T20 is good for the game. I don’t even call that cricket. It’s Barnum and Bailey circus entertainment,” he says bluntly.

Circus he isn’t, but entertainment Holding insistently is. Like his bowling once did with batsmen at the other end, Holding’s innate modesty, charm and forthrightness have always penetrated every cricket enthusiast’s soul.