The five-day Test, what many term the “purest format”, actually became the norm just about 40 years ago — in 1979 — and the jury is out on whether the administrators should revert to a four-day fixture as was common till about the late 1940s to make the game more attractive for the future.

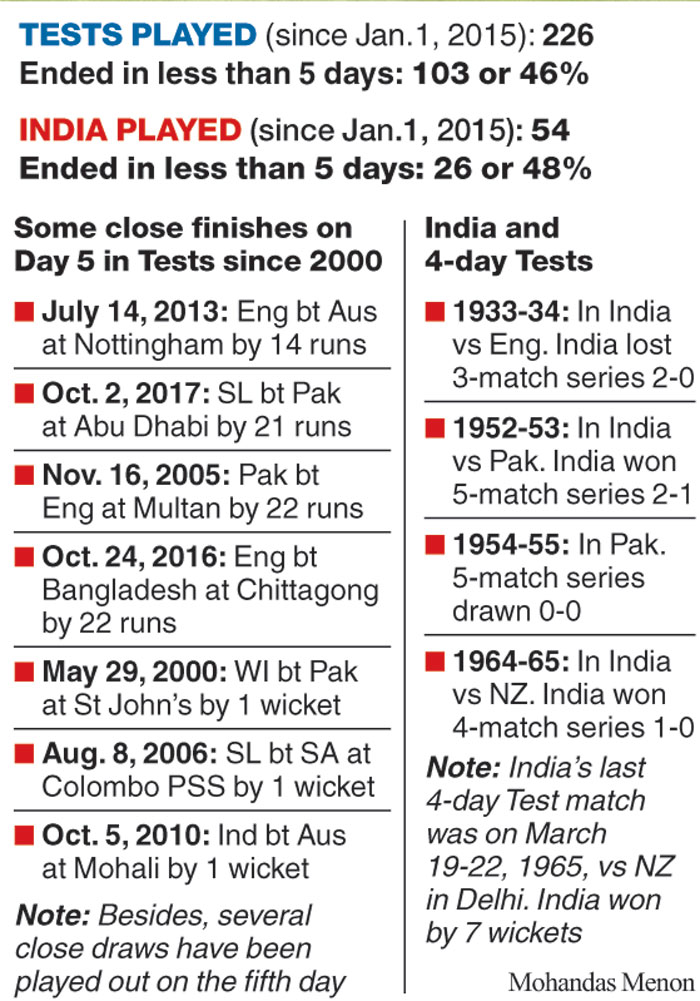

It is true that some of the most thrilling finishes of modern times, including India’s come-from-behind win against Australia at Eden Gardens in 2001 and the draw at the Oval that sealed England’s historic 2005 Ashes win — have been played out on the final day. But given the cramped cricket calendar of the modern era, the four-day proposal is gaining traction among a large section of players, administrators, broadcasters and followers of the game.

The proposal is set to be discussed at the International Cricket Council’s cricket committee meeting in end-March as part of efforts to rejuvenate the longest format of the game.

England has proffered support to the idea along with Cricket Australia. “We believe it could provide a sustainable solution to the complex scheduling needs and player workloads we face as a global sport,” a spokesperson for the England and Wales Cricket Board has been quoted as saying.

Kevin Roberts, the chief executive of Cricket Australia, has said mandatory four-day Tests were “something that we have got to seriously consider”.

One of the strongest opponents has been India’s captain Virat Kohli. “According to me, it (the format) should not be altered. As I said, the day-night is another step towards commercialising Test cricket and you know, creating excitement around it, but it can’t be tinkered with too much. I don’t believe so. You know the Day-Night Test is the most that should be changed about Test cricket, according to me,” he said a few days ago.

Proponents of four-day matches have suggested a minimum of 98 overs each day instead of the 90 now. The Tests are expected to start on Thursdays and finish on Sundays, allowing fans to catch the climax at the stadium. This, a section of administrators believe, could ensure better scheduling of Tests, allowing for three days off between matches. This would imply that a two-Test series could be played out in as little as 11 days, and a three-Test series in just 18 days, freeing up time in the calendar.

The Telegraph

‘Commercial aspect’

The idea of four-day Tests has been considered intermittently by the ICC since 2003. Many broadcasters have supported the proposal, as it would reduce the uncertainty associated with fifth days. With many Test matches finishing in less than five days in the last decade, broadcasters have been left in the lurch because they have to bear the cost of logistics even if the game does not make it that far.

Former India opener Arun Lal feels the “commercial aspect” is the sole objective behind having four-day Tests.

“The idea is purely commercial. While commerce is important, a proper balance has to be maintained. Don’t forget we will be forsaking a lot if we go for four-day Tests,” Lal told The Telegraph.

Star Sports or Multi Screen Media (Sony), the official broadcasters in India, didn’t wish to comment till details were known about the format.

In 2014, Star Sports won the global broadcast rights for all ICC events between 2015 and 2023 for a reported sum of $1.98 billion (Rs 11,880 crore), 80 per cent more than the previous cycle’s $1.1 billion.

Market analysts feel the sum will increase substantially in the next 2023-2031 cycle if four-day Test matches become mandatory as part of the World Test Championship.

The ICC has already proposed that during its next eight-year cycle (2023-2031) it would have one ICC global (both men’s and women’s) event every year: two 50-over World Cups, four T20 World Cups and two editions of an additional tournament, which is understood to be in the 50-overs format.

“If more days are freed as a result of four-day Tests, it will be easier for the ICC to slot more tournaments. That will mean more money from broadcast rights and more revenue. You’ve got to understand the dynamics behind every move,” said a market analyst.

“There’s also talk that the BCCI is contemplating slotting a second IPL every year. If the demand for event windows is met, then why not have four-day Tests? Who cares about purists? It’s a money-driven world.”

Lal, however, made his displeasure clear. “We already have enough cricket. We wouldn’t like to sacrifice the essence of five-day Tests. The character of the game will be lost… The mental attributes, the physical fitness.

“The art of patience and grinding it out on a fifth day wicket with the spinners banking on the vicious turn and uneven bounce from the roughs…

“The team composition will change. A lot will be lost. What happens if a half or full day is lost… Getting a result will always not be easy,” Lal said.

Former Australia captain Mark Taylor had advocated a four-day format in 2016. Speaking to Sports Entertainment Network, he had said: “It’ll only add to the appeal of the game, make it a bit shorter and a bit faster. That’s what people of this generation want to see. You’ve got one less day to win, lose or draw a game, so it does force captains and players to be a little bit more aggressive in their thinking.”

Varied durations

Those in favour of lopping off a day pointed out that Test matches have, since their inception in 1877, been of varied durations — the very first Test played at Melbourne was a timeless one, though it ended in four days with Australia beating England by 45 runs. Test matches in England were of durations ranging from three to four days until 1949; all Tests in Australia were timeless ones till the mid-1940s.

Tests hosted in India in 1933-34 were of four-day duration. India then had five-day games for a while but went back to a four-day format versus Pakistan in 1952.

Though these timeless Tests had been abolished by 1950, that did not mean that five-day cricket was adopted as a norm. The Tests during England’s tour of Pakistan in 1969-70 were of four days each.

In 1974-75, Tiger Pataudi’s India and Clive Lloyd’s West Indies were tied 2-2 when the final Test began at the then newly laid Wankhede Stadium. The two boards agreed to play a six-day Test. The visitors won thanks to Lloyd’s unbeaten 242 in the first innings and Vanburn Holder’s burst of 6 for 39 on the sixth day.

The last full four-day Test series was the one hosted by New Zealand against Pakistan in 1972-73. Pakistan won the series, which was marked by the debut of a certain Sir Richard Hadlee, who would go on to achieve greatness, and Rodney Redmond, the left-handed New Zealand opener who scored 107 and 56 in the only Test he played in (at Auckland) but was never picked again.