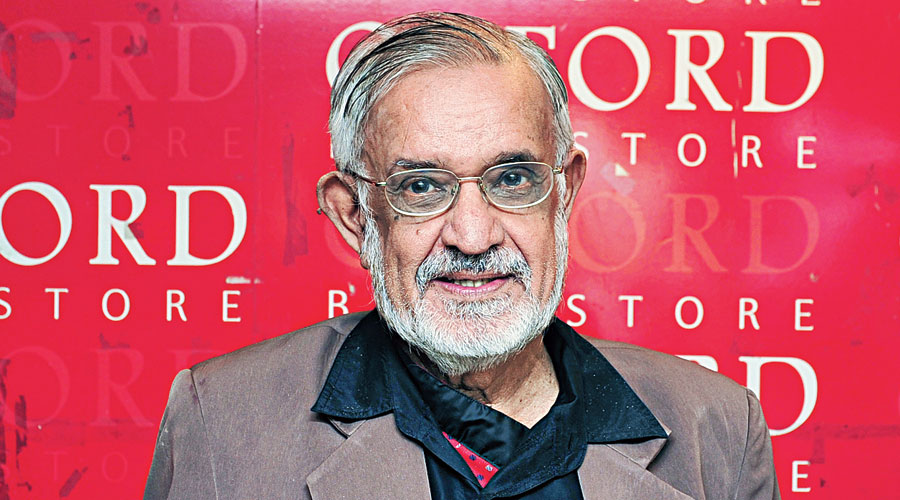

Kishore Bhimani was a decent bloke.

He would pepper every fourth conversation with a reference to ‘Mick’ (Jagger, with whom he had studied at London School of Economics) and eyebrows would arch.

He would talk of how a great Indian spinner bowled long hops in the West Indies because he was ‘high’ from an evening’s excess.

He could tell you of how he was carrying letters signed by a minister who was raising funds in the name of Indira Gandhi in 1980 without realising the gravity of what was in his hands.

He could tell you stories of the historic 1978 resumption series in Pakistan where Mehdi Hassan would tell him ‘Kishore saab, kya sunna pasand karenge?’

He could tell you stories of how an ex-Pakistan captain friend had thrown a party in his shaan in Lahore, only for it to be raided on the suspicion that the hosts had brewed their liquor.

He could tell you that a superstar cricketer reneged on his zubaan to play as a result of which the India-Pakistan exhibition game after the World Cup 1987 could not be organized (and Kishore took the flak for being ‘colonial’).

Kishore was not just full of stories. That’s a simplistic thing to say. He was full of dramatized stories – if he was quoting the Rolling Stone he would be speaking Cockney from the left corner of his mouth; if he was imitating Javed Miandad he would be touching his tongue to his upper front teeth; if he was Imran Khan the ‘throw’ would be from the back of his throat; if the fancy took him, he could recite Sanskrit mantras, quote Shakespeare or the Wisden extract on Bishen Bedi in the same exhale.

Forget the cricket writer or commentator, what we lost was a character who should have been prompted, recorded and archived.

Kishore described himself as the ‘Mercedes journalist’ who inherited his father’s business, preferred to write cricket for a living, had a keener ear for a bourse tip than who was likely to score how much on a turning wicket, finished his day’s descriptive for The Statesman within five minutes of the match ending while the Dicky Rutnagars slaved into 8pm evening after evening, tracked and commentated on horses, spirited himself away to London each summer, referred to the rich and famous by their first names, stayed at the best hotels with the Indian team when he travelled (he spoke of ‘Westmoreland’ as if it was his jaagir), attracted cricketers because he hosted ‘must attend’ parties and was at one time seen as an extension of Jagmohan Dalmiya.

There was another side of Kishore that few knew of. He bet on people. He gave me a couple of experimental assignments in 1979 when I was 17; he trusted his gut to offer me a job on the Sports Desk of the venerable Statesman before I was eligible to vote; he was taking on the white-bearded establishment that suffixed names with ‘Esquire’ and where you knocked three times on the teak before opening the door three inches to check if you could enter. He got me a Letter of Appointment; I ‘manned’ the desk for three days before a letter arrived from the Personnel Officer asking me to present myself before him. I did, expecting to be congratulated for breaking a Statesman record for the paper’s youngest journalist recruit; on the contrary, I was asked of my career plans and I must have lathered it well enough for the great man to write ‘Won’t stay long with us…too ambitious’. The result is that I was asked to ‘surrender’ my Appointment Letter, which I did with innocent haste without even a Xerox copy or a legal opinion on the ‘humiliation-induced stress’.

Kishore never forgot. He provided private assignments on behalf of The Statesman that must have netted the teenager a consolidated Rs 775 across 20 months, three bylines in my own name and 11 ‘By a special correspondent’ bylines I could show to the ‘wasters’ on Mission Row as proof of my having arrived in life. Besides, I could always be Kishore’s official flunkey; I could speak Her Majesty’s English, had been to the same school, understood a bit of cricket, was too young to possess an ego and could run his errands.

The attention was not wasted; he gave me confidence. He never told me ‘You write well’ but he let me hang around at his parties for the cricketers; he got me a break on Doordarshan during the double-wicket tournament where Sir Gary Sobers turned his arm over; he got me to liaise with the players and fly them from Delhi to Calcutta; he asked if my father could recite Quranic dua in the hospital room after Miandad was hit by a Lillee bouncer; when he asked me to ‘Drop Gavaskar’ from the Vidya Mandir Hall after a seminar on a rest day evening in my Fiat jalopy, I not only drove but I remember that my 65-year-old father got so excited that he skipped an urs of a saint at the masjid to sit in SMG’s company.

That’s what Kishore could do. He could lift. He could regale. He could entertain. He could delegate. He could inspire.

I asked around in our irreverent Sportsworld group – to get praise out of them is like extracting blood from stone - and even though their experiences had been nowhere as proximate as mine, they had largely the same things so say. David McMahon said Kishore had been welcoming when he entered the Madras Press Box in 1979. Pradeep Paul called him a ‘decent bloke’.

So that is what Kishore was to us, to his friends and to the world at large.

A decent bloke.