The bungalow was built for a Dutch trader in colonial times, but it has become part of modern Singaporean lore. It was where Lee Kuan Yew lived for decades, where he

started his political party and where he began building Singapore into one of the richest countries in the world.

Lee had said that he wanted the house to be demolished after he died rather than preserved as a museum, with the public “trampling” through his private quarters.

But the wording of his will left the property’s fate in limbo and caused a rift between his three children — one that reflects an intensifying debate over Singapore’s semi-authoritarian political system.

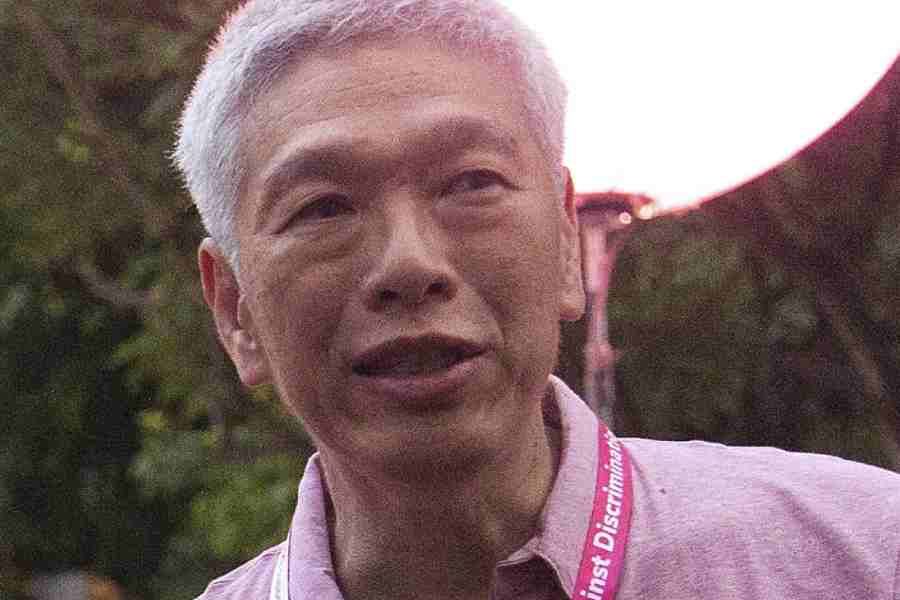

Now, an extraordinary voice has joined those who complain that the city-state’s prosperity has come at the cost of a government that lacks accountability: one of Lee’s

own children.

“The idea that one good man at the centre can control this, and you just rely on his benevolence to ensure that everything is right, doesn’t work,” Lee Hsien Yang, the youngest child, who wants to honour his father’s wishes for the house, said in a recent interview with The New York Times from London.

After Lee Kuan Yew’s death in 2015, the eldest child, by then Singapore’s Prime Minister, argued that his father’s instructions for the bungalow were ambiguous. His siblings wanted it demolished, though one continued to live in the house, and as long as she did, its fate remained unresolved.

Then, after the sibling’s death in October, the dispute resurfaced — and escalated sharply. Lee Hsien Yang, called Yang by his parents and siblings, announced that he had obtained political asylum in Britain because he feared being unfairly imprisoned in Singapore over the disagreement.

Yang, 67, described what he called a pattern of persecution by the Singapore government in recent years. In 2020, his son was charged with contempt of court for criticising Singapore’s courts in a private Facebook post. That year, his wife, a lawyer who had arranged for the witnesses at the signing of the patriarch’s will, was barred from practising law for 15 months. Then the couple faced a police inquiry about lying under oath. In 2022, they left Singapore.

In October, Yang announced that Britain had granted his asylum request, ruling that he and his wife “have a well-founded fear of persecution and therefore cannot return to your country”.

Singapore’s government rejected the claims, saying that the couple were free to return home. It said it was accountable to voters and an independent judiciary. Yang, it added, was engaged in “an extravagant personal vendetta” against his brother, Loong.

Loong, 72, who now holds the title of senior minister, declined to comment because he has recused himself from the matter of the house.

For Yang, the yearslong dispute is proof that thereare “fundamental problems in the way Singapore is governed and run”.

The People’s Action Party has governed Singapore with a tight grip for nearly 70 years. And years after the founding father’s death, it continues to praise his legacy.

This, some analysts say,has left Singapore at a crossroads.

“Are we able to move on?” said Ja Ian Chong, who teaches political science at the National University of Singapore. “Or are we still stuck with this relatively brittle, big-man kind of approach to politics?”

Lee Kuan Yew transformed a colonial outpost into an economic powerhouse in a generation. He made no bones about intervening in the lives of Singaporeans and prioritised the community over the individual — a notion that some observers say points to the irony of the family feud.

He “understood that the government would have to preserve the house if itdecided that was in the public interest”, Loong wrote in a 2016 letter to LawrenceWong, who was part of a government committee created to consider options for theproperty and is now the Prime Minister.

That panel concluded that the bungalow had historical significance, and that Lee Kuan Yew had been amenable to its preservation. But polls indicate that most Singaporeans want it torn down.

In October, the government said it was again studying whether to preserve the circa 1898 house.

‘The best combination’

For decades, Lee Kuan Yew’s family appeared to be as orderly as the state he ran. His wife, Kwa Geok Choo, was in charge of the household at 38 Oxley Road, in one of Singapore’s most expensive areas.

In the 1950s, Lee and a group of friends set up his political party, the PAP, in the basement dining room. Most of the house was spartan. The furniture was old and mismatched; the family bathed by scooping water from earthenware vessels. Even after the sons had married and moved out, they gathered every Sunday for family lunch.

Visitors were quick to notice that only one child’s photographs were displayed: Loong’s.

“He got the best combination of our two DNAs,” Lee would tell local journalists. “The others have also combinations of both, but not in as advantageous a way as he has. It’s the luck of the draw.”

“He was the apple of my mother’s eye, and she had ambitions for him,” Yang said of Loong. “I was never antagonistic with him, neither did I have any jealousy or envy of him.”

In 2004, Loong became the Prime Minister. Yang at the time was the chief executive of Singapore’s state-owned phone company and said that he harboured no political ambitions. That would change.

Demolition debate

After Lee’s wife died, he continued to live in the house with his daughter, Lee Wei Ling, a neurologist. Lee died in March 2015, and his children gathered at the bungalow the following month for the reading of his will.

The house was left to Loong, but Ling could continue to live there. Once she moved out, the house was to be torn down. And if for some reason, the house was not demolished, he did not want it to be open to the public.

Loong was blindsided and would later say publicly that he did not know about this final will. When the will was being discussed, he became “aggressive” and “threatening”, his sister wrote in a previously undisclosed email to a friend in May 2015. She added that Loong told his younger siblings that if they pursued the demolition clause, the government would intervene and declare the house a national monument.

It was the last time Loong spoke with Ling and Yang, according to Yang.

The next day, Loong raised the matter in Parliament. He said that he wanted to see his father’s wishes carried out, but that “it will be up to the government of the day to consider the matter”.

A few months later, it appeared that the siblings had reached a resolution. Yang bought the house from Loong for an undisclosed price.

But soon, the government formed a committee to explore options for the house. That marked the start of Yang’s troubles with the state.

New Opposition party

Loong told the panel that he was “very concerned” that the demolition clause in the will was “reinserted under dubious circumstances”. He asked whether there was a conflict of interest for Lee Suet Fern, Yang’s wife, who had organised the signing of the will.

To the younger siblings, it appeared that the committee was “conducting an inquisition into the will”, Yang said, pointing out that a court had declared it as binding.

In a joint statement in 2017, Yang and Ling said that they did not trust their brother as a leader. They said that Loong and his wife were milking “Lee Kuan Yew’s legacy for their own political purposes”, and harboured dynastic ambitions for their son.

Loong responded in Parliament, saying that he did not give instructions to the committee and that his only dealings with the panel were his responses to their requests in writing.

He has denied grooming his son for office.

Then the government accused Yang’s wife of professional misconduct over the will. A disciplinary tribunal ruled against her, saying she and her husband had built an “elaborate edifice of lies” during the proceedings.

The walls of 38 Oxley Road are now cracked, and rust has eroded part of the gate. When a reporter rang the doorbell on a recent Sunday, a housekeeper answered and said nobody was home.

New York Times News Service