Dropouts

Though Indians are reigning at the junior level, the same cannot be said for the senior level. The Indian chess community has a problem of dropouts. Guttula says top junior Indian players take a break from the game around age 20 because it doesn’t have any career prospects.

Akash Thakur, Nagpur-based chess coach, agrees that most players drop out because of career pressure. “Players want a secure future. With the immense competition in this field, they are right in their view,” he says.

Anand told The Telegraph that he if he had had a lean patch around the time of a critical academic exam, he may have given up too. “I was very fortunate in my career that just before my 10th standard exams or before I chose my subjects, I became the national champion. I finished my Plus II exams and I became world junior champion and grandmaster. When I finished my BCom, I was number five in the world,” he said.

India is unlikely to challenge the traditional domination of Russia and Europe unless more young grandmasters think it worthwhile to stick on. “We need to work on the mindset and guide our top junior players so they feel highly positive and motivated about making a full-fledged career in chess,” says Guttula. He believes that not just coaches but parents have a pivotal role to play for this change to come about.

Coach Thakur adds another solution. “Maybe, if the Government intervenes and encourages the game, things will soon look up,” he says.

We need some real competition

India’s digital edge has helped with our chess proficiency. Players are exposed to styles all over the world. “A player’s IQ level, quick reflexes, fast decision-making and control over nerves improve with online practice,” says Grand Master Himanshu Sharma.

But this can only be a supplement. A live game bring into play nerves, tension, the ego and the psychological tangle between two players. Ramesh says, “If a player’s work ethic consists of only playing online, then it probably won’t help much.” Our players need the exposure of real tournaments.

In open tournaments, players of any age and level can participate by paying the stipulated entry fee. But it is the closed tournaments, which attract the top players, where we need some more activity. As they are expensive and chess is not yet a spectator sport, India doesn’t host them. And it is in these closed events that are best can meet and compete with the world’s best.

Ramesh says, “We need more tournaments focusing on the very strong players in India which will give our players a chance to play with very strong international players.” Guttula agrees that we need super grandmaster events. “A Super GM tournament needs sponsorship. We have never got such kind of a financial backing so far to invite the top players from the world to play in India.”

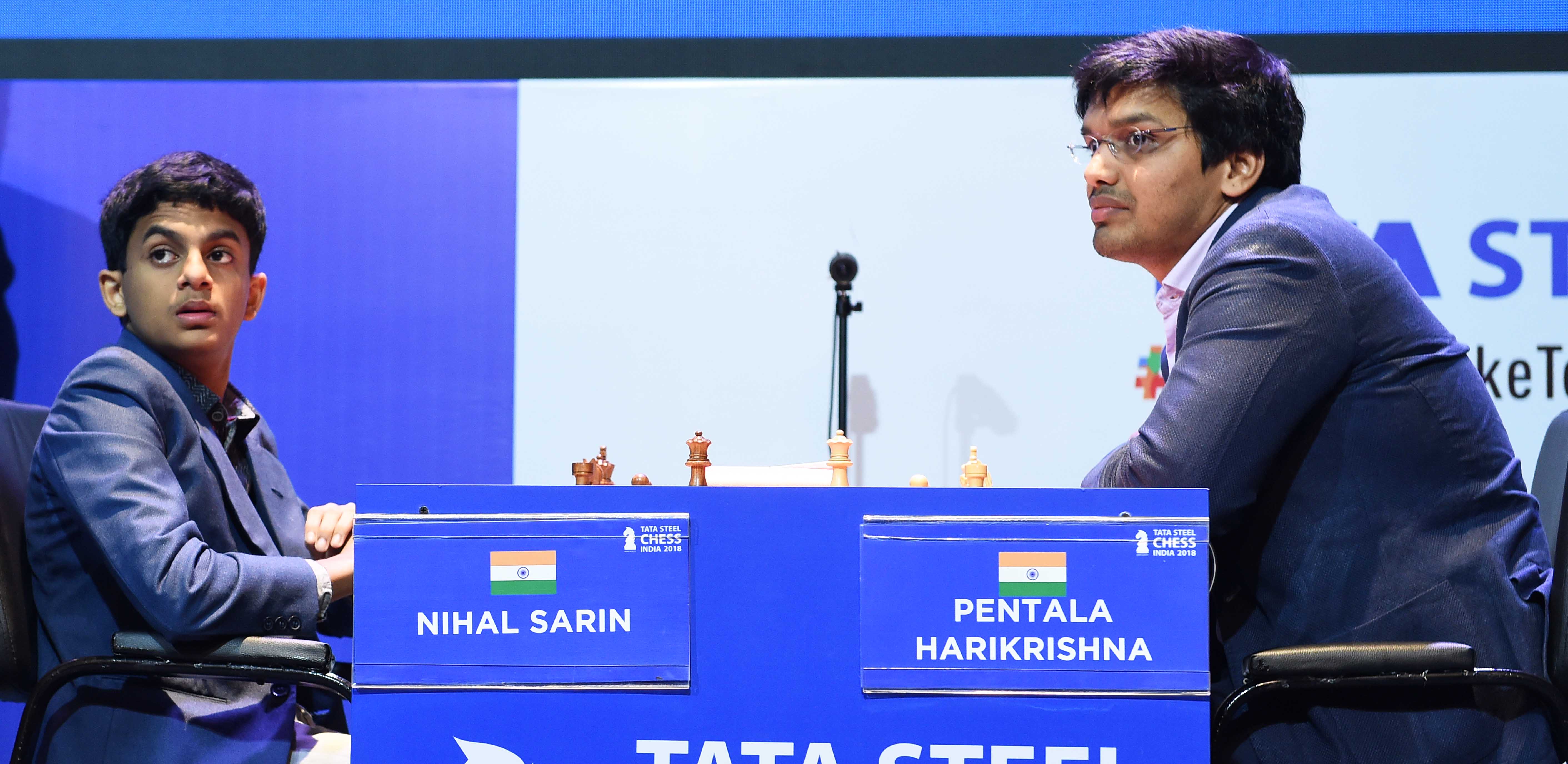

There’s some good news on that count now. India hosted its first Super GM tournament from November 9 to 14, 2018, in Kolkata. The Tata Group came forward to sponsor it and it's likely to continue. Here’s to an opening gambit that pays off.

It’s hard to say that 2018 has been a good year, unless you’re talking about Indian chess. We now have 58 grandmasters – the highest title Chess players can get – and rank 8th in the world for our count. In June, R Praggnanandhaa, from Tamil Nadu, became the world's second-youngest chess grandmaster at the age of 12 years and 10 months. The fourth spot among youngest grandmasters is occupied by Parimarjan Negi, 13 years and 4 months. We have had more new grandmasters in 2018 than in any other past year.

So if you’re looking for a boom – and are coming up disappointed - look at the game of 64 squares. India may well be tipped to have the maximum chess champions in the world in the next decade.

In June, R Praggnanandhaa, from Tamil Nadu, became the world's second-youngest chess grandmaster at the age of 12 years and 10 months Image: The Telegraph

India is believed to be the birthplace of chess, the game called Chaturanga, and Shatranj in Urdu. While there are many reasons to rejoice that we are regaining our stakes in the game, there are also some challenges that have kept India from producing another Anand.

Young old game

On the bright side, this old game is getting younger. Sagar Shah, International Master in 2014, CEO Chessbase India says, “Parents are introducing their children to chess between the ages of three and four years. We used to have grand masters at 12 but now the game is getting younger each day.”

How then do parents and coaches decide who should join up? “The most essential quality at such a tender age is nothing but a keen liking or love towards chess. The child has to enjoy the company of this beautiful game,” Balaji Guttula, FIDE master and coach of South Mumbai Chess Academy (SMCA) says.

Coach Ramesh supports the idea. “It is possible to learn most difficult concepts at a young age. It is better to start young and achieve as much as possible before school related pressures start,” he says.

Schools also play a key role in identifying young talent and nurturing it. Players get exposure when the institution helps them represent their school in inter-school games at the state as well as national level. It is particularly helpful when they are able to attend international tournaments in countries such as Russia, Greece and England. Principal of Father Agnel School in Navi Mumbai, Father Saturnino Almeida, says, “Our students, accompanied by their coaches and parents, regularly go for invitational tournaments, which gives them a first-hand feel of international competition.”

The result is there for all to see. According to media reports, among the top 100 male juniors (under 21 years) in the world, there are 12 Indians, as of November 2018. We stand second only to Russia, which has 14. Among female juniors, there are 11 Indians while Russia has 21.

Nihal Sarin and Pentala Harikrishna at Tata Steel Chess India 2018 Image: The Telegraph

The Anand effect

It was Vishwanathan Anand who put India on the global map of chess and he’s the one who has kept us there. Anand was the World Champion from 2007 to 2012. This has brought some attention to the sport and inspired many young minds in a country not known for doing its best for sportspeople. “During my career, I have seen how India’s relationship with chess changed. It’s very different now from before,” he said to The Telegraph in an interview.

Anand is excited about the talent the country is showing right now. “Praggnanandhaa (Rameshbabu) and Nihal Sarin are showing outstanding qualities at such young ages,” he told The Telegraph. “But even if you look at the older guys… (Pisharodi) Vidyut is doing very well,” he added.

Anand’s home state Tamil Nadu boasts of 15 grandmasters, the maximum from any state. Now other parts of the country are also generating chess geniuses. A registered player needs to earn three norms (a high level performance) and an Elo rating of 2500 to be a grandmaster. We now have three players with a rating above 2700, says R B Ramesh, who has been the coach for the Indian chess team for 12 years. The Chennai-based founder of Chess Gurukul, which has helped budding chess players since 2008, says, “At the top level, our players have been consistently increasing rating points. We now have three players above 2700 rating compared to only one (Anand) a few years ago. It’s definitely an encouraging sign.”

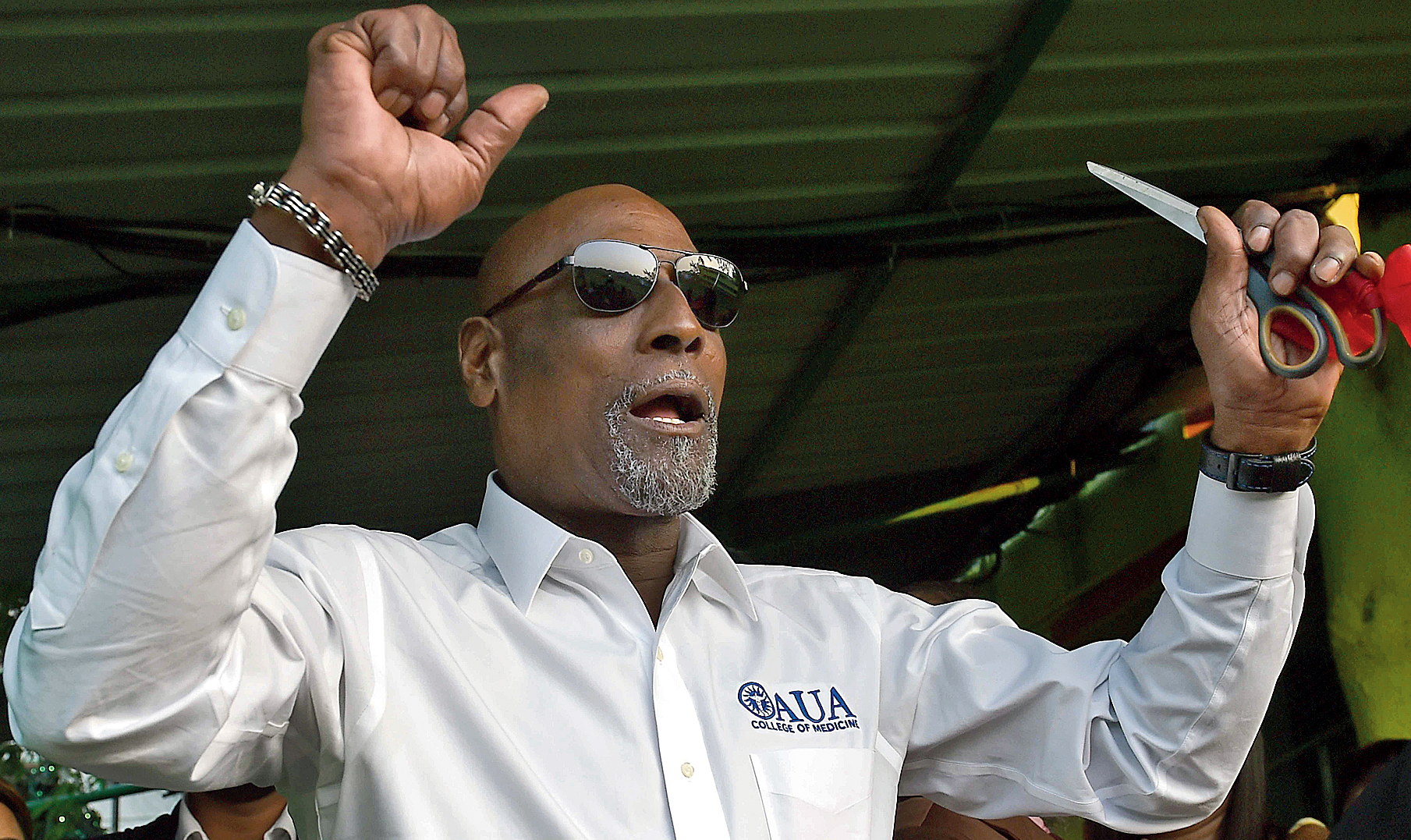

Vishwanathan Anand put India on the global map of chess. He was World Champion from 2007 to 2012 Image: The Telegraph