It was something he had never been able to get over. Even after so many years. Any discussion on back volleys invariably brought back memories of one image. Of a man on his back, airborne save for an elbow, inverted legs thrust astride against the air’s gravity.

And then, catastrophe.

No, let’s be fair, catastrophe for one half of those who were there at the ground.

It was August 6, 1978, derby day of the Calcutta Football League that year, and Shyam Thapa, tiny, mercurial darling of the stands — or villain, depending on which side of the divide you were — had just let rip the most monstrous bicycle kick the Maidan had ever seen.

Everything had conspired to that moment of precision strike; the body’s buoyancy, legs in a duet of rhythm and balance over narrow fulcrum hips, an imperceptible transfer of weight. And a stab of searing agony.

The scoreline read Mohun Bagan-1, East Bengal-0. If despair had a taste, it must have been a lot like bile for fans of East Bengal that day. For an 11-year-old, it was innocence lost.

Redemption would come many times against the arch rivals, some soon, others later, including a 4-1 triumph in the 1997 Federation Cup, but that scissor kick remained in memory. Alongside spectacular triumphs, like the one three years earlier in the IFA Shield, a 5-0 glut and inventory for future reprise.

Shyam Thapa, ironically, had scored two of those goals. Now he was on the other side — football’s version of seasonal mutability.

But why begin a story about a team that has just turned hundred with an incident of defeat? Wouldn’t a tale of triumph been more befitting?

There’s a counterpoint to that. Victory is sweet but it’s disappointment that lingers, though time puts the solace of distance between incident and memory. Fandom lives and riles through such memories. The collective fancies of a people who have committed — and condemned — themselves to a life of loyalty to an idea.

For the boy who watched that 1978 derby on TV, East Bengal was that idea.

It was an intimacy that began early at home. Only later would he learn about the history, how the team that traced its roots to the land of his ancestors came to be, and of those difficult Partition days of exile and exodus when a cocktail of factors like community, circumstance, lie of the land and a river’s geographical meander would come to define identity and social acceptance.

He had heard a story often. It was about a long-dead ancestor who rode a horse to work. That was somewhere in Pabna in modern-day Bangladesh, at the turn of the last century. Then one day, this ancestor had patted the horse, handed the reins to an aide, about-turned and taken a boat to this side of Bengal.

East Bengal was still more than a dozen years away — and Partition a few dozen more — but the gene pool of future support had already taken shape.

For the record, East Bengal was born out of protest. On a July day in 1920, a match had been scheduled between Mohun Bagan and town rival Jorabagan. When the Jorabagan players limbered out, one man was missing from the starting eleven, defender Sailesh Bose.

The club’s vice-president, Suresh Chandra Chaudhuri, wanted Bose in but didn’t have his way. He left the club and later, along with some others, formed East Bengal on August 1, 1920. The name was in deference to the origins of the club’s founders. All of them were from the eastern part of what was Bengal then.

And so it began — a journey now one hundred years old and a tale of rivalry that has continued.

If Mohun Bagan was largely the club for people native to this side of Bengal, East Bengal was for those who had come from the other side or traced their origins there: the response of the rootless to the entrenched. Of displaced refugee to settled gentry.

At the psychological level, it offered an identity in alienation. Football as salvation for those compelled or denied by circumstance.

So what did East Bengal mean to a boy growing up in Calcutta in those nostalgic seventies? It meant just that: growing up.

Banter in classroom. Brawl outside. Red-and-Gold of hope and dare. The silvery hilsa of triumph. Quarantine of defeat. And the furious consolation of statistics.

It meant six straight Calcutta league titles from 1970 to 1975. And a 5-0 bragging right. Seldom had the margin of victory in a final been so extravagantly absurd.

On the field of play it meant Surajit Sengupta’s magical dribble, Samaresh Chowdhury’s vision, Bhaskar Ganguly’s temperamental acrobatics, Sudhir Karmakar’s clinical dispossession of an intruder, Subhas Bhowmick’s sturdy slide across wet ground, Mohammed Habib’s defence-ripper pass, Ulaganathan’s knife-through-butter run, a wall called Monoranjan Bhattacharya and Majid Beshkar’s wizardry of chest, knee and foot. How easy the Iranian made it look; trap, drop and volley.

It meant a mercurial midfielder called Sudip Chatterjee, among the most brilliant of them all, a Nigerian powerhouse named Chima Okorie, and a “Sikkimese Sniper” called Bhaichung Bhutia.

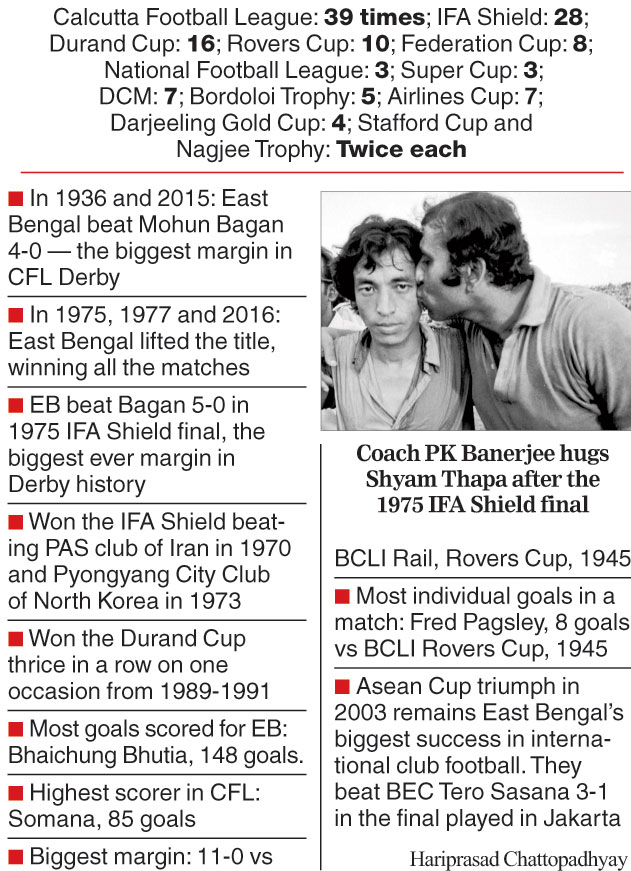

And then there was P.K. Banerjee. Another memory stirs. Federation Cup, 1980. The transfer season had emptied out East Bengal’s star strength but PK, Olympian, now astute and pragmatist coach, turned the team around, helped by Majid and his compatriot Jamshid Nassiri. East Bengal had ended as joint champions with Mohun Bagan that year.

In a way the parity in scoreline was acceptable. It meant experience gained in adversity — after that loss of innocence two years earlier.