Pele, one of football’s greatest players and a transformative figure in 20th-century sports who achieved a level of global celebrity few athletes have known, died on Thursday in Sao Paulo. He was 82.

His death, in a hospital, was confirmed by his manager, Joe Fraga.

A national hero in his native Brazil, Pele was beloved around the world — by the very poor, among whom he was raised; the very rich, in whose circles he travelled; and just about everyone who ever saw him play.

“Pele is one of the few who contradicted my theory,” Andy Warhol once said. “Instead of 15 minutes of fame, he will have 15 centuries.”

Pele, for many, was the standard-bearer of the beautiful game that the Giants of Brazil, as the footballers became famous as, became known for. In 1977, Calcutta got its tryst with Pele when he came to the city with the New York Cosmos to play in a match against Mohun Bagan at Eden Gardens. The match ended in a 2-2 draw

Celebrated for his peerless talent and originality on the field, Pele also endeared himself to fans with his sunny personality and his belief in the power of football to connect people across dividing lines of race, class and nationality.

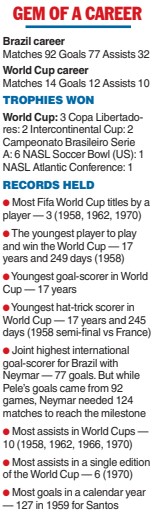

He won three World Cup tournaments with Brazil and 10 league titles with Santos, his club team, as well as the 1977 North American Soccer League championship with the New York Cosmos.

In his 21-year career, Pele scored 1,283 goals in 1,367 professional matches, including 77 goals for the Brazilian national team.

Pele sprang into the international limelight at the 1958 World Cup in Sweden, a slight 17-year-old who as a boy had played football barefoot on the streets of his impoverished village using rolled-up rags for a ball. A star for Brazil, he scored six goals in the tournament, including three in a semi-final against France and two in the final, a 5-2 victory over Sweden. It was Brazil’s first of a record five World Cup trophies.

Pele also played on the Brazilian teams that won in 1962 and 1970. In the 1966 tournament, in England, he was brutally kicked in the early games and was finally sidelined by a Portuguese player’s tackle that would have earned an expulsion nowadays but drew nothing then.

With Pele essentially absent, Brazil were eliminated in the opening round. He was so disheartened that he announced he would retire from national team play.

But he reconsidered and played on Brazil’s World Cup team in Mexico in 1970. That team is widely hailed as the best ever.

Edson Arantes do Nascimento was born on October 23, 1940, in Tres Coracoes, a tiny rural town in the state of Minas Gerais. His parents named him Edson in tribute to Thomas Edison. (Electricity had come to the town shortly before Pele was born.) When he was about 7, he began shining shoes at the local railway station to supplement the family’s income.

His father, a professional player whose career was cut short by injury, was nicknamed Dondinho.

Brazilian footballers often use a single name professionally, but even Pele himself was unsure how he got his. He offered several possible derivations in Pele: The Autobiography.

Most probably, he wrote, the nickname was a reference to a player on his father’s team whom he had admired and wanted to emulate as a boy. The player was known as Bile (bee-LAY). Other boys teased Edson, calling him Bile until it stuck.

One of Pele’s earliest memories was of seeing his father, while listening to the radio, cry when Brazil lost to Uruguay, 2-1, in the deciding match of the 1950 World Cup in Rio de Janeiro. The game is still remembered as a national calamity. Pele recalled telling his father that he would one day grow up to win the World Cup for Brazil.

He signed his first contract, with a junior team, when he was 14 and transferred to Santos at 15. He scored four goals in his first professional game, which Santos won, 7-1. He was only 16 when he made his debut for the national team in July 1957.

A New Way to Play

When Brazil’s team went to the World Cup in Sweden the next summer, Pele later said, he was so skinny that “quite a few people thought I was the mascot.”

Once they saw him play, it was a different story. Reports of this precocious Brazilian teenager’s prowess raced around the world. One account told of how, against Wales in the quarter-finals, with his back to the goal, he received the ball on his chest, let it drop to an ankle and instantly scooped it around behind him. As it bounced, he turned — so quickly that the ball was barely a foot off the ground — and struck it into the net. It was his first World Cup goal and the game’s only one, and it put Brazil into the semi-finals.

“It boosted my confidence completely,” he wrote in his autobiography.

“The world now knew about Pele.” The world now knew about Brazilian football, too. Pelé undoubtedly benefited from playing alongside other remarkably gifted ball-control artists — Garrincha, Didi and Vava among them — as well as from Europe’s lack of familiarity with the Brazilian style.

Most European teams used static alignments; players seldom strayed from their designated areas.

Brazil, though, encouraged two of the four midfielders to behave like wingers when attacking. This forced opponents to cope quickly with four forwards, rather than two.

Making things more difficult, the forwards often switched sides, right and left, and the outside fullbacks sometimes joined the attack. The effect dazzled onlookers, not to mention opponents.

After the semi-final against France, in which Pelé scored a hat-trick in a 5-2 Brazil win, the French goalkeeper reportedly said, “I would rather play against 10 Germans than one Brazilian.”

The team went home to national acclaim, and Pelé resumed playing for Santos as well as for two Army teams as part of his mandatory military service. In 1959 alone, he endured a relentless schedule of 103 competitive matches; nine times, he played two games within 24 hours.

Santos began to capitalise on his fame with lucrative postseason tours. In 1960, en route to Egypt, the team’s plane stopped in Beirut, where a crowd gathered threatening to kidnap Pele unless Santos agreed to play a Lebanese team.

“Fortunately, the police dealt with it firmly, and we flew on to Egypt,” Pelé wrote in his autobiography.

He had become such a hero that, in 1961, to ward off European teams eager to buy his contract rights, the Brazilian government passed a resolution declaring him a nonexportable national treasure.

Football Diplomacy

When Pele was about to retire from Santos in the early 1970s, Henry Kissinger, the United States secretary of state at the time, wrote to the Brazilian government asking it to release Pele to play in the United States as a way to help promote soccer, and Brazil, in America.

By then, two more World Cups, numerous international club competitions and tireless touring by Santos had made Pelé a global celebrity. So it was beyond quixotic when Toye, the Cosmos’ general manager, decided to try to persuade the player universally acclaimed as the world’s best, and highest paid, to join his team.

The Cosmos had been born only a month earlier, in one afternoon, when all the players had gathered in a hotel at Kennedy International Airport to sign an agreement to play for $75 a game in a country where soccer was a minor sport at best.

Toye first met with Pele and Julio Mazzei, Pele’s longtime friend and mentor, in February 1971 during a Santos tour in Jamaica. It took dozens more conversations over the next four years, as well as millions of dollars from Warner Communications, the team’s owner, for Pelé to join the Cosmos.

During that period, he became the top scorer in Brazil for the 11th time, Santos won the 10th league championship of his tenure, and Pelé took heavy criticism for retiring from the national team and refusing to play in the 1974 World Cup, in West Germany.

In June 2014, the city of Santos opened a Pelé Museum just before the start of the World Cup, the first held in Brazil since 1950. In a video recorded for the occasion, Pelé said, “It’s a great joy to pass through this world and be able to leave, for future generations, some memories, and to leave a legacy for my country.”

Advocate for Education

Pele met Rosemeri Cholbi when she was 14 and wooed her for almost eight years before they married early in 1966. They had three children — Kelly Cristina, Edson Cholbi and Jennifer — before divorcing in 1982.

After his divorce, Pelé often appeared in the gossip pages, partying with film stars, musicians and models. He acted in several movies, including John Huston’s Victory (1981), with Michael Caine and Sylvester Stallone.

It also emerged that he had fathered two daughters out of wedlock. One, Sandra, whom he had refused to acknowledge, later sued for the right to use his surname. She wrote a book, The Daughter the King Didn’t Want, which he said greatly embarrassed him. She died of cancer in 2006.

His son, nicknamed Edinho, was a professional goalkeeper for five years before an injury ended his career. He later went to prison on a drug-trafficking conviction.

In 1994, Pelé married Assiria Seixas Lemos, a psychologist and Brazilian gospel singer; their twins, Joshua and Celeste, were born in 1996. They divorced in 2008. In his later years he dated a Brazilian businesswoman, Marcia Aoki, and he married her in 2016.

Children always responded warmly to Pelé, and he to them. Neither big nor intimidating, he had a wide, easy smile and a deep, reassuring voice.

“I have never seen another human being who was so willing to take the extra second to embrace or encourage a child,” said Jim Trecker, Cosmos’ public relations director in the Pele years.

Pele was sensitive about having dropped out of school (he later earned a high school diploma and a college degree while playing for Santos) and often lamented that so many young Brazilians remained poor and illiterate.

Indeed, the day he scored his 1,000th goal, in November 1969 at Maracana stadium in Rio before more than 200,000 fans, Pelé dedicated the goal to “the children.” Crying, he made an impromptu speech about the difficulties of Brazil’s children and the need to give them better educational opportunities.

New York Times News Service