All day, there had been noise. The songs had started early in the morning, as the first few hundred fans appeared on Wembley Way, flags fluttering from their backs.

The songs started as soon as the train doors opened at the Wembley Park underground station, the paeans to Gareth Southgate and Harry Maguire, the renditions of Three Lions and Sweet Caroline, and they grew louder as the stadium appeared on the horizon.

Inside, the noise rang around, gathering force as it echoed back and forth when it seemed England was experiencing some sort of exceptionally lucid reverie: when Luke Shaw scored and the hosts led the European Championship final inside two minutes and everything was, after more than half a century, coming home.

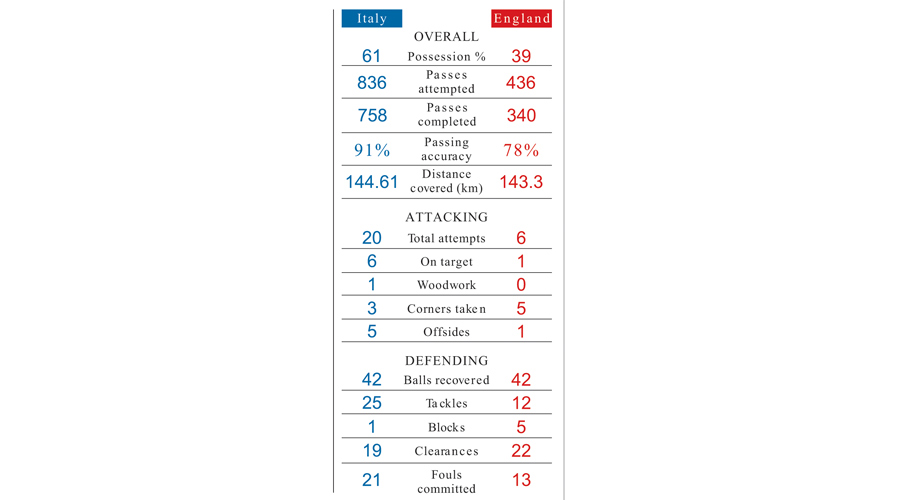

There was noise as Italy scrapped and clawed its way back, taming England’s abandon and wresting control of the ball, Leonardo Bonucci’s equaliser puncturing the national trance.

There was noise before extra time and before the penalty shootout, the prospect that haunts England more than any other.

What all of those inside Wembley will remember, though, is not the noise but the sudden removal of it, the instant absence of it.

Italy’s journey does not have the grand historical sweep of England’s, of course — it won the World Cup only 15 years ago, and that is not the only one in its cabinet — but perhaps the story is actually about a country that did not even qualify for the World Cup in 2018, that seemed to have allowed its soccer culture to grow stale, moribund. Instead, it has been transformed into a champion, once again, in the space of just three years.

Roberto Mancini’s Italy has illuminated this tournament at every turn: through the verve and panache with which it swept through the group stage, and the grit and sinew with which it reached the final. And how, against a team with deeper resources and backed by a partisan crowd, it took control of someone else’s dream.

It felt England was losing the initiative, but really Italy was taking it.

Andrea Belotti was the first to miss for Italy in the shootout. Wembley exulted. It roared, the same old combustion, releasing its nerves into the night sky.

Marcus Rashford stepped forward. He had only been on the field for a couple of minutes, introduced specifically to take a penalty.

As he approached the ball, he slowed, trying to tempt Gianluigi Donnarumma, the Italian goalkeeper, into revealing his intentions. Donnarumma stood still, calling his bluff. Rashford got to the ball, and had to hit it. He skewed it left. It struck the foot of the post.

Jadon Sancho missed, too, his shot saved by Donnarumma. But so did Jorginho, Italy’s penalty specialist, when presented with the chance to win the game. For a moment, England had a reprieve. Perhaps its wait might soon be at an end. Perhaps the dream was still alive.

Bukayo Saka, the youngest member of Southgate’s squad, walked forward. England had one more chance.

And then, just like that, it was over. There was still noise inside Wembley, from the massed ranks clad in blue at the opposite end of the field, pouring over each other in delight. But their noise seemed muffled, distant, as if it were coming from a different dimension, or from a future that we were not meant to know.

New York Times News Service