Not until the 84th minute in Munich on Wednesday night was it clear who is heading where from Group F. Away in Budapest, where France were playing Portugal, the game had oscillated — Portugal led, then France, then Portugal struck back — and so had their fates, dependent to some extent on the outcome of the game between Germany and Hungary in Munich. At one point or another, each of the four teams had believed they were going through. Only once Leon Goretzka had secured Germany a point against Hungary with six minutes left to play was it all settled. Hungary would be the fall guy; the three favourites all had safe passage to a round of 16.

Time for the real business to begin. But what did we see and learn from the past 12 days?

France still favourites

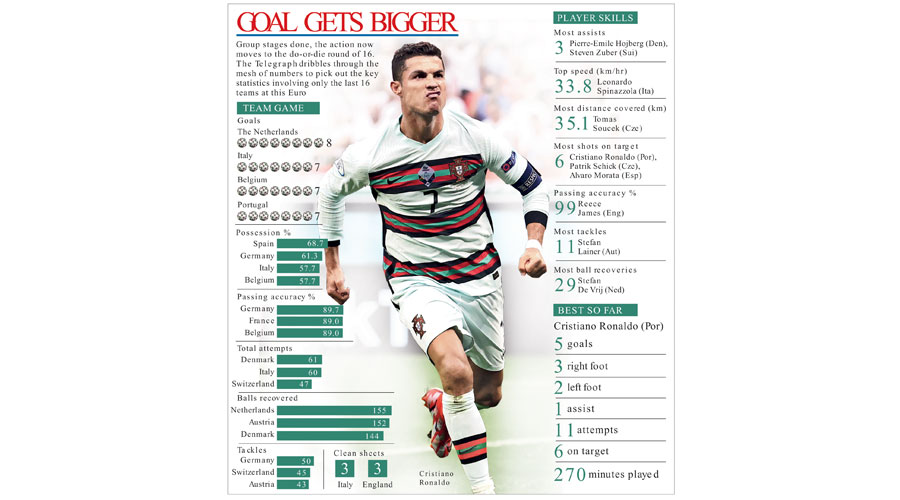

The reigning world champion may not have sailed through their group like some of their challengers have — Belgium, The Netherlands and Italy all posted perfect records — but don’t be fooled.

The calibre of their opponents was higher: France dropped points to Portugal, the defending European champions, and a spirited Hungary team. Just as significant, particularly in their final game, France managed to give the impression that they have more to offer as and when necessary. Whenever Adrien Rabiot, Paul Pogba, Karim Benzema and the rest needed to lift the rhythm, they did so seamlessly. Kylian Mbappé has not scored yet, but that will not hold forever. This is still France’s tournament to lose.

Italy’s timing

Italy have won all three group games. They have played thrilling, inventive soccer, backed by a raucous and partisan crowd in Rome. They are also yet to concede a goal, because deep down, they are still Italy.

Roberto Mancini’s team should breeze past Austria in the first knockout round, but Belgium, their most probable opponent in the quarter final, would provide a sterner test.

Italy benefited from the postponement of this tournament as it granted Mancini’s young side invaluable experience.

The converse is true of Belgium. Roberto Martínez’s team also have won all their games, but they have done so with none of the verve or panache that has marked Italy’s progress. Belgium are the world’s top-ranked team, but they also have the oldest squad in the tournament. It has the air of a team whose moment has just passed. Italy’s, you sense, is yet to come.

Some have it easier

On Saturday, Wales face Denmark in Amsterdam. Both finished as the runners-up in their groups. But so did Austria, and they must play Italy.

The need to squeeze in two games in the round of 16 between second-placed teams, to make the whole format work, has the effect of unbalancing the draw. That has been mitigated a little this time by the fact that Spain could not top their group, and will face Croatia in Copenhagen. But the consequence is clear: Some teams have a much more challenging route to the final than others.

Belgium, for example, must first face Portugal, then endure a potential quarter final with France, before meeting Spain — perhaps — in a semi-final. On the other, England and Germany meet in the first knockout tie, but the prize for winning is a rich one: a quarter final against Sweden or Croatia, and then most likely The Netherlands in the semi-finals.

An uneven draw allows a route to the latter stages for nations that would, in other formats, expect to be dispatched far earlier. But it also rather exposes the logic that it does not matter when you face the major powers: To win the tournament, after all, you have to play them at some point. The problem is that, sometimes, you have to face more of them than others.

Swiss & Swede stories

Neither Switzerland nor Sweden play an especially adventurous style — though the Swiss did turn on the style against Turkey — and neither particularly captivate the imagination.

But that should not detract from what an achievement it is for two countries — admittedly extremely wealthy ones — with a combined population of less than 20 million people to stand so tall, so consistently among the superpowers of Western Europe, the countries that have effectively turned developing young soccer players into an industrial process.

In this lies a lesson for two of Europe’s most populous nations — Turkey and Russia. Turkey have not even been to a World Cup since their third-place finish in 2002. They made the semi-finals of Euro 2008, and have not played a knockout game since.

Russia were a semi-finalist in 2008, too, and reached the quarter finals in their home World Cup three years ago. But those represent a paltry effort for two countries with such a vast reservoir of talent.

The causes of those respective failures are not uniform — Russia do not export players, Turkey do not develop nearly enough of them — but there is one binding thread: Both Russia and Turkey are isolationist soccer cultures, resistant to the cutting-edge thinking and best practices that emanate from the leagues to their west. More than anything, both need to import ideas. They could start their learning journey by looking at the Swiss, and the Swedes.

Written with inputs from NYTNS