Life was vastly different in the mid-1980s in India. So was the world of sport and entertainment. Shyam Benegal and Adoor Gopalakrishnan were at their creative best in the squeezed space of parallel cinema. Amitabh Bachchan occupied all 10 positions in the cinema ratings. India were the new world champions of cricket under Kapil Dev. Mohun Bagan and East Bengal were still considered the last word in Indian football.

For a youngster born and brought up in Delhi and eager to get a glimpse of the best of cricket and football in the city, it was all about shuttling between the iconic Feroz Shah Kotla ground and the Ambedkar Stadium, separated only by a wall.

The big guns of Delhi cricket — Mohinder Amarnath, Surinder Amarnath, Madan Lal and Kirti Azad — routinely hammered the opposition at Kotla; Krishanu Dey, Narender Gurung, Sudip Chatterjee, Chima Okerie and company dazzled capacity crowds in the Ambedkar arena with their amazing dribbling skills, spectacular through passes and terrific shooting prowess. Everyone went home happy. Truly contended. They felt proud to be part of the show.

And then, Doordarshan decided to play spoilsport in 1986 — by deciding to telecast live the matches of the World Cup in Mexico. Having come under pressure from a few football-loving members of Parliament, its decision to showcase the greatest show on earth was like an ecstatic burst of thunder from a cloudless blue sky. With the World Cup, Doordarshan unwittingly inaugurated in our lives Diego Armando Maradona. The way Indians, especially the young, perceived the game of football was forever altered. It wouldn’t be the same. Never.

In the 1986 World Cup, Maradona tutored the world on what class was actually about, what needs to be achieved on the sporting field to create one’s exclusive hall of fame. Dribbler. Cutter. Runner. Weaver. Kicker. Scorer. A Swish swashbuckler of a battery-pack the game had never seen. But the diminutive Argentine’s godly skill and pugnacity was only the creamy layer of the show. Underneath, his influence ran deep, wider than La Plata river on the border between Argentina and Uruguay. Wider, in fact, than the world had the appetite or the grit to embrace. Watching and following Maradona was to grasp the fact that football is not part of a larger-than-life show. It is life itself. And Maradona was at the centre of it.

For someone mad about sport, this realisation was far more important than Maradona’s second strike against England in that famed game that left the sporting world dumbstruck. He made one believe there was no shame in equating sports and politics or to say it publicly that beating England in Mexico was like beating the country Argentina had lost their claims on the Malvinas (Falkland Islands) to and a revenge for the pain inflicted in the war. Maradona forever believed the knock delivered by England in the Falklands was a far greater crime than sending the ball into the back of the English net with a nudge of his left hand.

One knew what one actually thought when B.S. Chandrasekhar spun England out in the historic Oval Test in 1971, but was afraid to spell it out. Sports and politics shouldn’t be mixed, he was taught from childhood. Chandrasekhar kept it to the cricket. Maradona was blunt and extrovert about extending his exploits before the field of play. It was time to unlearn some of the politeness.

During a chance meeting with Maradona many years later, I received his unapologetic grandstanding on matters beyond football first-hand. “I am ready to react,” he told me, “(On) Anything that concerns me and my people, I have a right to say what I want to.” Then, as I mulled a follow-up, he added: “Off the field a sportsperson is a human being, too.” He was speaking in Spanish, his mother tongue, and being simultaneously translated by his interpreter.

Maradona didn’t stop there. He had more to say. He suddenly jumped up and pulled his trousers up his shins to show off the famous tattoo of Fidel Castro he had on his left leg. It certainly looked more like a part of the show; not a spontaneous move but a calculated, well-rehearsed demonstration. Overall, he was far more captivating than a top cricketer coming to a press conference before a crucial match and paying obeisance to demonetisation as the most charming decision he had come to experience in his 27 years on this planet.

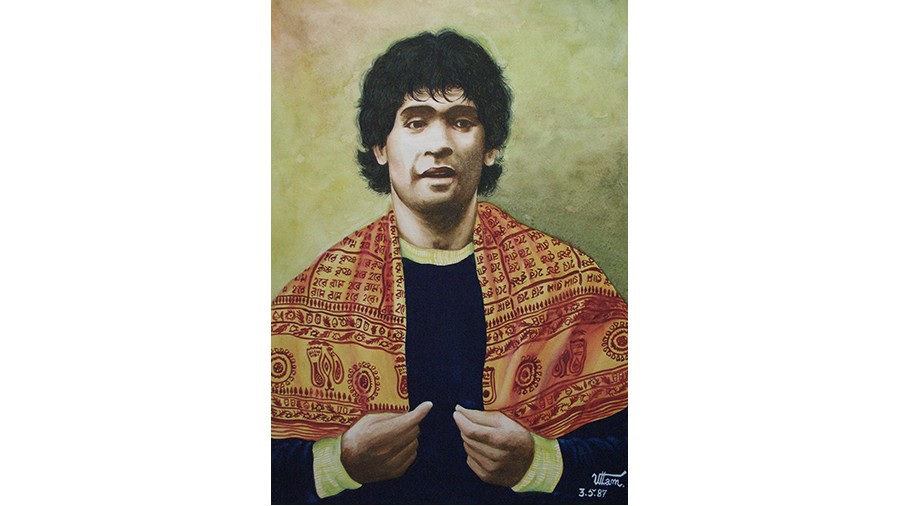

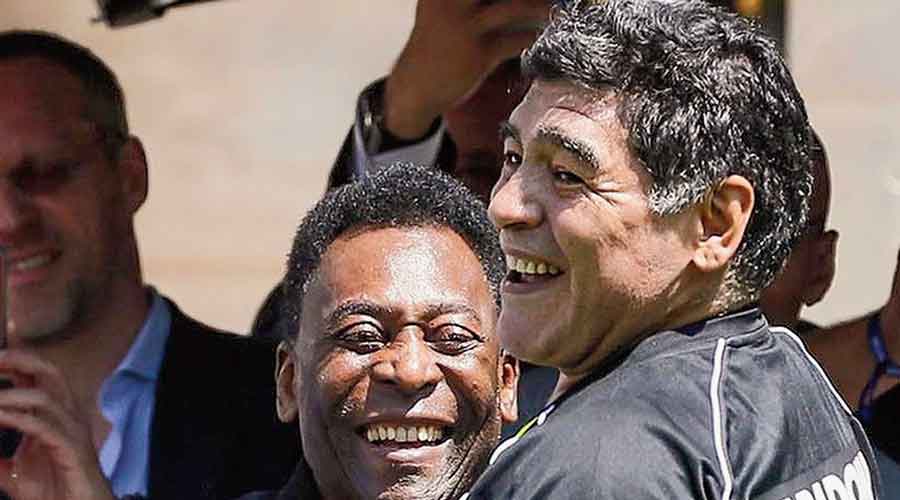

In the 1986 World Cup, Maradona tutored the world on what class was actually about, what needs to be achieved on the sporting field to create one’s exclusive hall of fame. File Picture

Maradona’s death has been described as untimely. Rightly so; 60 is no age, not for a top-notch sportsman. But it is perhaps not far to state that Maradona, the man and his manner, had become a little outmoded; he had fallen behind the conformisms of the time. One gets the distinct feeling that Maradona had become old-fashioned and outdated. In India, it is now considered neo-normal to wish the sports minister on his birthday and copy-paste texts supplied to them by authorities on social media handles. When a sportsperson is cleared of drug charges, the delighted president of the sports federation makes it a point to strategically put up the photo of the prime minister behind him before he talks to television journalists.

Maradona wore his anti-establishment politics on his sleeves and spoke out for the people of Palestine; he openly supported Left-wing Latin leaders like Hugo Chavez, Evo Morales and Lula da Silva. That probably rendered him a misfit in the scheme of the world, an outlier at any rate. But to him none of that mattered — Maradona believed what he did and he never hesitated to let you know.

From 1986 onwards, Maradona truly changed the world of football and the followers of the game. Football could be a team game, but when Maradona was around, one eye needed to be riveted on him. Often for the wrong reasons too, but never mind. During the 1998 World Cup in France, Maradona was still a persona non grata in Fifa’s books because of his drug offences. His presence was patently and palpably welcome in France. Any questions on Maradona that World Cup were frowned upon.

But when he arrived in Marseilles midway through the championship, the number of television crews at the airport vastly outnumbered the passengers. In the hustle and bustle, he decided to hold a show of his own. He juggled with the ball and then placed it on an empty bottle of Coca-Cola without disturbing the bottle. Top Argentine coach Jose Pekerman, who was there as an expert TV commentator, shook his head in disgust and said: “What is he up to? He shouldn’t reduce himself to this.”

Sadly, Pekerman was right. For a person, who grew up accepting Maradona’s genius as part of his normal daily life, that period, broadly the years after 1990, was a time of pain and anguish. As his footballing ability and lifestyle went from bad to worse, the very understanding of a long-cherished sporting ethos and values fell apart. All that he did and said looked increasingly bizarre, even unreal. He could be easily accused of making people believe what he himself never practised.

Yet, even during that trough Maradona had plunged into, he had the ability brighten up people who saw him as a warrior for the human and humane face of the game. In the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, his regular press conferences as the Argentina coach at Pretoria always drew huge numbers of journalists. One time, a journalist from Italy asked him a question. As soon as he finished, Maradona leapt up from his seat and jostled through the crowd of stunned mediapersons to hug the Italian. It was revealed that the journalist was once the third choice goalkeeper of Napoli and Maradona was simply so delighted to see him after all these years that he had to hug him. No other coach in the World Cup would do that. For sure.

As Maradona’s troubled life came to an end in Buenos Aires this Wednesday, it was curtains for those who had dared to dream that Maradona still had the power to rescue the game, to prevent football and sports in general from being hijacked by lobbies that actually had little to do with the game.

Having become a creature dominated by the corporate world, public relations exercises and calculating, manipulative agents in the last few years, football badly needed fresh air and doses of maverick spontaneity and adventure, such as Maradona possessed, to bring it back to the earth, to turn it once again into a beautiful game. Maradona, the widely believed flawed genius, was still the best bet. He forever displayed the promise and guts to swim against the tide. Unfortunately, he couldn’t live up to the promise; all he did in the process was turn into an unscripted chapter of that famous book called The God That Failed.

The writer, formerly of The Telegraph, covered two World Cups for the paper including the 2010 tournament in South Africa when Maradona played coach to Argentina