Ever heard of Béla Guttmann’s curse? Guttmann, a Hungarian football coach known for his futuristic out-of-the-box thinking that often left opponents playing catch-up, was in charge of the Benfica side that won the European Cup — now the Uefa Champions League — beating fancied Real Madrid in the final played on May 2, 1962, at Amsterdam.

The match, which the Portuguese side won 5-3, is hailed as among the greatest European Cup/Champions League finals ever. It was also the last time Benfica would win the title, or any other European crown. “Because of Guttmann’s curse” is the legend ascribed to this lack of success.

So what exactly happened?

For the first five seasons of the tournament, from 1955-56 till 1959-60, Real Madrid pretty much won everything — they were victorious in each of those years, with their 7-3 triumph over Eintracht Frankfurt at Glasgow in 1960, still the biggest margin in a Champions League final.

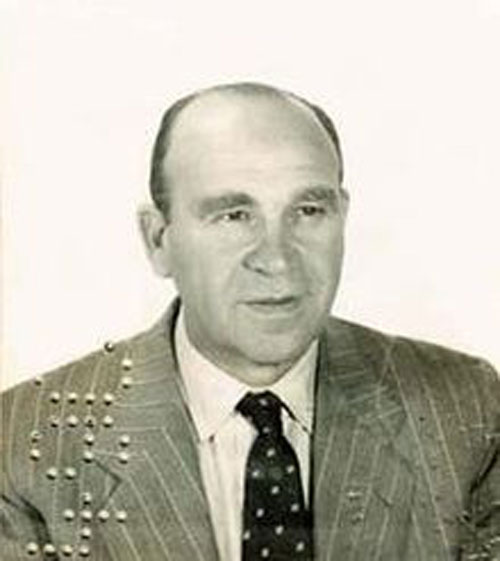

Benfica, a Lisbon club then owned by coffee baron Mauricio Vieira de Brito, began their rise following the signing of Guttmann, a Holocaust survivor, as coach in 1959. Guttmann’s coaching methods of man management, rigorous fitness regimen and tactical innovation had indirectly contributed to Brazil’s 1958 World Cup win. Guttmann was then coach of Sao Paolo, where he started the innovative 4-2-4 system, something the club’s stars carried with them to the Brazilian national team.

Around the same time, Portugal was going through a socio-economic change within. Then controlled by the autocrat Antonio Salazar, Portugal, in a bid to boost its economy, allowed in immigrants from its erstwhile North Africa colonies like Mozambique and Angola to add to its workforce. Salazar’s ideology for his despotic rule was based on the three Fs — Fado, Fatima and Football. The migrant workers found in the sport a hobby that united them.

Mozambique-born inside-right Mario Coluna, and Angola-origin players such as Joaquim Santana and Jose Aguas formed the backbone of Guttmann’s team as Benfica broke Real Madrid’s stranglehold on the continent to win the 1961 European Cup with a 3-2 defeat of Iberian rivals Barcelona.

And then came a prodigy named Eusebio. While playing for the Maputo club Maxaquene, he was spotted by former Brazil and Sao Paulo player Bauer, who recommended him to Guttmann. Maxaquene was a feeder club of Benfica’s Lisbon rivals Sporting, who objected to the transfer. But Benfica convinced the teenager’s family and Eusebio landed in Portugal in December 1960, unknown to most people. He was whisked away to a seaside town and kept in a hotel there under a false name before being unveiled for Benfica in the summer of 1961.

Eusebio burst onto the stage scoring 27 goals in 30 games during his first season before facing Real Madrid titans such as Ferenc Puskas, Alfredo Di Stefano and Francisco Gento in the 1962 European Cup final on May 2 at the Olympisch Stadium in Amsterdam, so named after the 1928 Summer Games.

The teams started with the traditional W-M formation. Used to great effect by Arsenal’s Hebert Chapman in the thirties, it was so called because the 3-2-2-3 formation led to the letter “W” on the defender’s side and the letter “M” on the forward’s side.

But while Madrid were largely rigid, sometimes shifting to 4-2-3-1, Guttmann’s Benfica soon changed to playing in the more innovative 4-2-4 formation. This opened up the space for Eusebio, one of the fastest footballers of all time who could move back and forth at lightning speed.

By half time Madrid were ahead 3-2, thanks to a spectacular hattrick by Puskas (he also scored four goals in the 1960 final, making him the only person with two hattricks in a European Cup/Champions League final).

But Benfica’s 4-2-4 play helped. After 50 minutes Coluna equalised from 25 yards before Eusebio took charge. He made a dash for the goal and won a penalty in the 64th minute, which he blasted in, and five minutes later hit home from 30 yards with an exquisite free kick.

A new superstar had arrived. A humbled Di Stefano handed Eusebio his Real Madrid shirt after the final whistle, a treasured piece of football memorabilia.

But it would be the last time Benfica would win the European crown.

The morning after the triumph, the story goes, Guttmann, who had never held on to a managerial post for more than two years, went to see the Benfica board of directors and demanded a pay rise. The board refused, in what must be one of the biggest rejections in corporate sporting history.

As he walked away in anger, a gutted Guttmann told the suits: “Not in a hundred years from now will Benfica ever be European champions again!”

It never has. “Guttmann’s curse” continues to haunt Benfica.

On May 2, 1962, Benfica won their second consecutive European Cup, driven by a 20-year-old genius named Eusebio. But in the 58 years since, a European crown has eluded the Portuguese giants